In the years immediately following the codification of the Laws of the Game in 1863, soccer as it was played would have borne little resemblance to how it is played today. Some differences would have been obvious. For example, goal kicks weren’t introduced until 1869 and goalkeeper wasn’t a recognized position until 1872. Referees weren’t included in the Laws of the Game until 1880. Crossbars weren’t mandatory on goals until 1882 (tape or a section of rope was typical before then), nets weren’t required until 1892. It wasn’t until 1909 that the goalkeeper was mandated to wear a differently colored shirt than his teammates and not until 1912 was he restricted to handling the ball only in his own box.

The evolution of the Laws of the Game aside, how players were organized in their effort to score goals also evolved over time. As Jonathan Wilson explains in Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics, what we think of a “shape,” or the formation or position of players on the pitch, and how this influences the development of tactics, would take several decades to approach even a basic form that would be recognizable today. By the time organized soccer began in Philadelphia in the late 1880s, the first soccer formation that would begin the mature development of the diverse tactics of the modern game, the 2–3–5, was firmly in place.

Evolving toward the 2-3-5

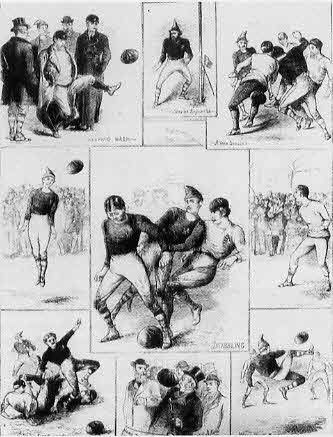

The original definition of Law Six—the offside rule—was strict in the extreme: “When a player has kicked the ball, any one of the same side who is nearer to the opponent’s goal line is out of play, and may not touch the ball himself, nor in any way whatever prevent any other player from doing so, until he is in play.” This meant that passing could only have been lateral or backwards and so encouraged the development of the “dribbling game.”

Dribbling in the early days of soccer was thought of differently from what we see today. The player with the ball, who may have been as unwilling to give up the ball to his teammates as to the opposition (we would have probably thought of the dribbler as a ball hog), would have charged at the opposition, backed up by his teammates, searching for some weak point to break through toward goal. Play would have looked something like rugby without the handling. Teams, more or less, simply chased the ball. The formation, such as it was, would have resembled something like a 2–9 or 3–8.

The liberalization of Law Six in 1866—a player was now considered to be onside when three players on the opposing team were nearer their own goal line—meant the possibilities of forward passing could begin to be explored. Local conventions of players and teams would have been as much a factor in their willingness to explore those possibilities as would have been any successful result from employing new tactics. For example, the culture of dribbling in some areas meant that heading the ball would have been seen as an oddity since there would have been little reason for the ball to leave the ground other than to lift it over a challenging foot or through accident. To such thinking, crosses in the air would have seemed strange and even unsporting.

Wilson suggests the spread of the passing game throughout the early football world—which at this point would have been Great Britain and Ireland—can be traced to soccer’s first international, between Scotland and England, in 1872. England played in a formation that was something like a 1–2–7. Scotland, made up of players from the Glasgow-based Queens Park Club, played in something like a 2–2–6. Though the match ended as a scoreless draw, that the Scotland side “played excellently well together” made a strong impression on the heavily favored England side. Scottish players would would be instrumental in spreading the idea of the “combination game”—dribbling and passing—in England.

The 1883 FA Cup Final, in which the professional Blackburn Olympic side used long passes from wing to wing to beat the amateur and dribbling side Old Etonians, marked both the rise of professionalism over the previously prevailing amateur ethic and the ascendancy of combined play. Tactically, over the course of the 1880s, it became the norm for one of the center forwards in the 2-2-6 formation to drop back from the front of a team’s attack to become the center half of the 2–3–5 formation, also known as “the Pyramid.”

The 2-3-5 in Philadelphia

The English, Irish, and Scottish immigrants who formed Philadelphia’s first soccer clubs and organized its first leagues brought the 2–3–5 with them. Early newspaper accounts of games regularly praise “a good combination game.” Descriptions of team rosters list goalkeeper, two full backs, three halfbacks, two right wings (one inside and one out), one center and two left wings (also one inside and one out) exclusively from the end of the 1880s into the 1920s.

It would not be until the further liberalization of the offside law in 1925 that an alternative formation would arise (see Julian Carosi’s The History of Offside for an informative overview of the evolution of the interpretation of the offside law). Since 1867, the offside law required three defenders in front of an attacking player moving to receive the ball for the attacker to be onside. In 1925, the Law was changed so that now only two defenders had to be between the attacker and the defender’s goal. This change in the offside law came about because the overwhelming effectiveness of the offside trap according to the old offside rule had resulted in too few goals, too many draws, and utterly boring games. With the new offside rule freeing up possibilities for the attack, the W-M formation (variously described as a 3–2–5, a 3–4–3, or a 3–2–2–3) was developed by Herbert Chapman at Arsenal. Other innovations would eventually follow around the world.

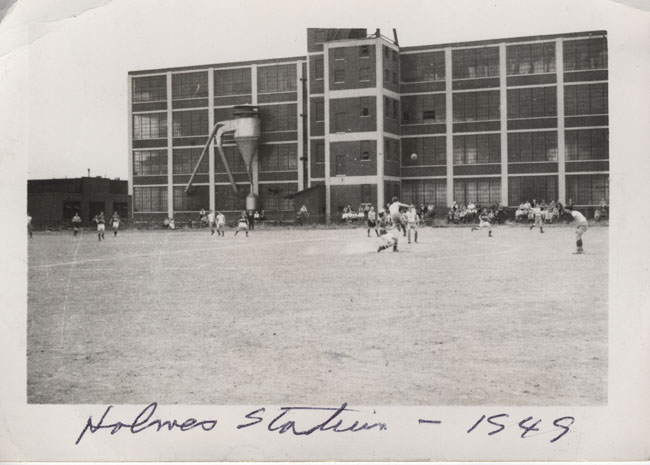

In Philadelphia, the 2–3–5 would remain the formation through the 1930s and 1940s. Describing his childhood in Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood, National Soccer Hall of Fame member Len Oliver wrote, “My earliest soccer memories were watching my father play in the late ‘30s…My father was a blur in his red and black jersey-running, passing, tackling, yelling—a 5’7” pesty Scottish center half moving up and down the field under the traditional 2–3–5, soccer’s mainstay system since the 1870s. And he seemed to be always full of mud.” Oliver may be incorrect in referring to the 2–3–5 as the “mainstay system since the 1870s,” but that it was the global default formation for decades is undeniable.

Describing his first coach at Lighthouse Boys Club, Ozzie Lynn — “a wrinkled, stolid Englishman who could still drive a ball 60 yards” — Oliver writes, “Coach Ozzie told us where to play, still in the traditional 2-3-5, and we did it…Raw, tough, hard soccer where we honed our skills, applying what we had learned in the streets to real, full-sided games. We now started to learn positions, heading (seldom done in street soccer), and a tactical sense of the game.”

A “new” formation arrives

It wouldn’t be until 1951 when he began playing at Temple University as a freshman under head coach Pete Leaness that Oliver learned a different tactical system. Oliver explained in an interview,

I always loved to run, to connect on the field, to be a catalyst for our forwards while doing my duty on defense, so the “W-M” System” was a natural outlet for any soccer talents I had. Leaness accepted the system and that’s what we played from then on—the “3-back game,” or “W-M” in coach parlance. It gave us more cover at the back, and freed up our midfielders to be playmakers with the Inside Forwards.

Once it became popular in American soccer, every team adopted the “Three-Back Game” as we called it at the time. Your links were the two midfielders and the two inside forwards, with a center forward and two wingers in attack.

So, just over a quarter century after its introduction, and at least a decade after it became the dominant formation in England, Oliver finally encountered the W-M.

Stationed in Germany with the US Army, Oliver traveled to the 1958 World Cup in Sweden and so was probably one of the first Americans to witness Brazil’s revolutionary 4-2-4.

I was a young GI stationed in Germany at the time of the 1958 World Cup in Sweden, so I just got on a train to Sweden, found tickets at the gate, and saw my first World Cup live. I was somewhat amazed to see Brazil come out with a 4-2-4 formation, but from the start of the game, Brazil’s outside backs kept going up the field to support the attack, almost a 2-2-6! Only Brazil could play this system, so it didn’t catch on as the 4-3-3 and the 4-4-2 did later in the 1960s and 1970s. Brazil’s 4-2-4 required attacking outside backs, who were always running the flanks, supporting the attack. Few teams had these types of resources.

So, while lining up in a 4-2-4, when Brazil transitioned into the attack their shape turned into “almost a 2-2-6,” coming full circle to the same formation employed by Scotland to such influential effect in 1872 against England. In the center of that circle for decades, in Philadelphia and elsewhere, was the 2-3-5.

A version of this article was originally posted at The Philly Soccer Page on January 14, 2010.

Pingback: The origins of soccer in Philadelphia, part 4: The first account of soccer-style football after codification? – Society for American Soccer History

Pingback: 1916: Bethlehem Steel FC travels to St. Louis – Society for American Soccer History