I’d like to introduce you to someone exceptional, also someone gone too soon. You’re going to meet a man who, in retrospect, might have been Washington’s first to be enshrined in the National Soccer Hall of Fame. Instead, his tale is a tragic one, where an individual’s flaw unfortunately proved fatal: He loved the game too much.

I doubt you know of William Patrick “Billy” McGrath. For that matter, most of our state’s newfound fans of soccer have no clue about Barney Kempton or Vic Weston or Eddie Craggs. All are hall of famers, Greater Seattle’s Mr. Soccer of their day; great players or coaches who, over several decades, were always finding new ways to put this game on proper or firmer footing so that it might survive, grow and become what it was destined to be, what it is today.

If there’s a Rushmore for Washington’s first 75 years as a footy community, those three – Kempton, Weston and Craggs – would have their faces chiseled into the mountainside. And the fourth position might well have been McGrath. If only, if only.

I first got to know Billy McGrath while scouring the local newspaper archives, discovering and curating content for what I hope to be a lasting and living testament to everyone who has ever contributed to Washington state’s golden standing in the football world. I’d been asked by a Museum of History and Industry (MOHAI) representative to examine some archival photographs that lacked captions or context. One photo in particular was puzzling and also inviting. It was a wide-angle shot of a game where spectators are surrounding the field seemingly at the edge of a forest, abutting a stand of trees.

Why Play on Easter?

The puzzling part was the date: April 17, 1927. Ever since association football first found its way into local published accounts in the final decade of the 19th century, Washington’s traditional season would conclude sometime in March. Yet here was a game of apparent magnitude being played on the third weekend in April, and on Easter Sunday, no less.

The reason for the exceptionally late play date was Billy McGrath. And if there had been a proper stadium, if there had been sufficient planning and if the match had not been played on such a holiday, who knows how may might have turned out. As it was, organizers expected 4,000 to stand several deep on a blustery, brisk afternoon. At that time, there had been only two soccer crowds exceeding that figure. McGrath’s teams had been involved in both.

By this time McGrath was widely known to the soccer community. And his gift was far greater than a timely tackle or thrust into the attacking third.

He might play, he might coach. He might do both. He was still being selected for all-star teams in his late 30s. McGrath was not one to put on airs. If a second-division team was short a man and he was not already officiating, McGrath would accept an invitation to play, sometimes in goal.

His devotion to the game went beyond the pitch and was also very personal. Jack, the eldest son of Billy and Margaret McGrath, starred first as a youth, and in 1923, as an 18-year-old, joined his father in uniform for West Seattle AC. Jack had a younger sister and brother.

West Seattle was McGrath’s home then. The family lived in the Gatewood neighborhood, not far from Lincoln Park. From there he could catch the streetcar, first to Spokane Street, then transfer to reach the Skinner & Eddy Shipyard west of Pioneer Square. There, McGrath worked as a fitting crew foreman for the city’s largest ship builder.

A Great Scot (and Sitter)

McGrath spoke with a distinct brogue. He banged the drum for a bagpipe band and proudly skippered the Seattle-based Scots in their annual holiday match versus the English expatriates. He and his wife were raised near Glasgow, Scotland, where they met and married. Together, they set off for a new world of opportunity, first settling in Saskatchewan before arriving in Puget Sound in 1906. They would reside in Tacoma, then Port Blakeley before finally putting down roots in Seattle.

His skills were sought-after. McGrath moved from club to club – no fewer than 10 in all. Early on, there’s a report of him beating four defenders on the dribble, and he figured among the league’s top scorers through much of his first 10 seasons. Then his attention turned to management, and he positioned himself on defense, usually left- or center-half. He was often lauded as one of the best defenders in state league history. At West Seattle, he played alongside both Barney Kempton and Vic Weston, the future hall-of-famers. No matter the role inside the lines, his teams kept winning.

Beyond trophies, McGrath was entrusted with practically everything associated with the game. He would referee or run the line at youth and senior matches. In 1926, he was also serving as a Washington State Football Association vice president, a position that can manifest itself from trophy presenter to ticket taker, although he also represented the state in talks with northern California clubs about starting an annual all-star challenge series. Beyond administration, evidently, he was also deemed trustworthy for watching children.

An oft-told tale involved a 1913 Seattle United-Carbonado contest played in Tacoma. Rough play spilled over to the chalked lines to supporters, and once the whistle blew a riot ensued. Standing off to the side, McGrath, then playing for United, was approached by a woman with a baby in arms. She asked him to hold her child so she could get into the fray.

One Last Trophy in Sight

By the time he turned 40, McGrath was far more a coach than player. Once his Maple Leaf side secured a sponsor and became Seattle’s Electro Dentists, only 13 names, including his, were added to the roster. Rarely did he step onto the pitch (substitutions would not be added to the laws for another 30 years), but when he did, he delivered. When a record crowd of 8,000 converged on Upper Woodland Park for a top-of-the-table clash with Todd Shipyards in November 1926, McGrath penciled himself in the lineup. That afternoon against Todds, the team he twice guided to the title, news reports singled-out his left-back play as “exceptional” despite a 2-1 loss.

Four months later, Electros emerged as state champion, and usually that would mark the season’s end. However, the matter of Best in Washington had been muddled of late. Longview’s Timber Barons, founded in 1924 on the Washington side of the Columbia River, had siphoned some stars from the Seattle area and by 1926 they had become by far the strongest club in Oregon’s competitions. That spring, the Timber Barons had beaten Todds for the so-called Northwest Championship, an outcome that Washingtonians found detestable. So, a rematch was in order the following year.

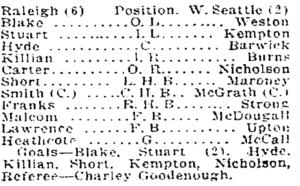

The Timbers Barons and Electros tangled during state cup play March 14 at Woodland Park. While the Seattle club prevailed, 3-2, the visitors had played shorthanded after losing a defender to injury in the first half. That in mind, McGrath and his players knew that his team would be underdogs on the road four weeks later.

One Final Match

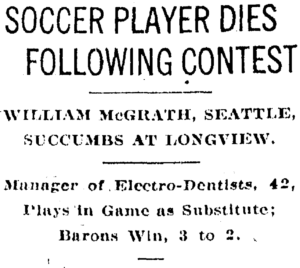

It took approximately a half-day to travel the 125 miles from Seattle to Longview. When the Electros assembled at the field that Palm Sunday afternoon, they were short one player; center-half Jimmy Craig was absent. Apart from the Todds match in January, McGrath had played only once, as goalkeeper. Two days earlier he had celebrated his 41st birthday.

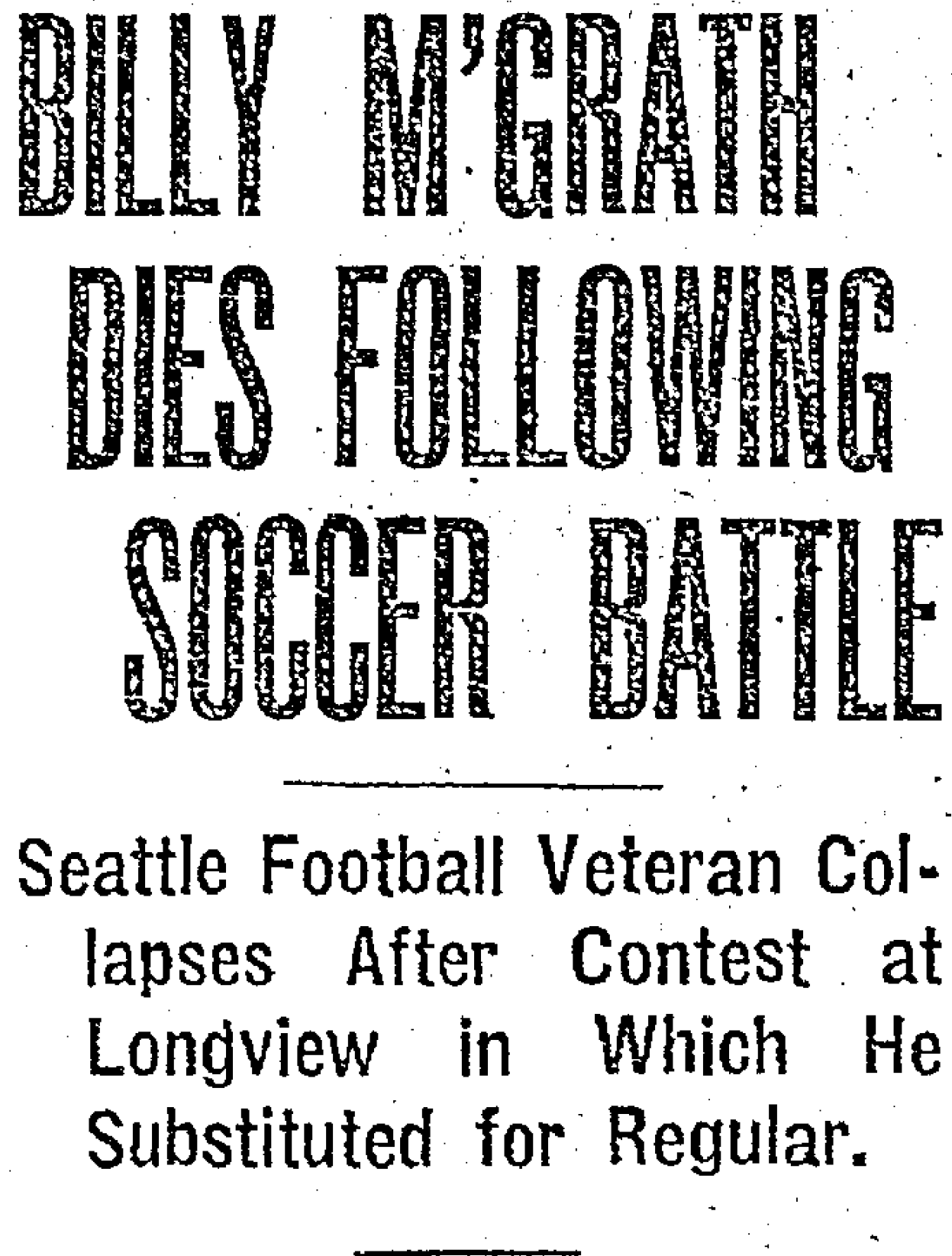

A 1924 newspaper profile described him then as “one of the oldest soccer players in point of service in this part of the country.” When asked by a Portland reporter about the condition of his team, McGrath responded, “They are all in good shape except me, but I oughtn’t be playing.”

By all appearances in photos, he seemed rather fit, and Dr. Reid, the Electros sponsor, claimed McGrath was in good health and “continuously active.” Later, however, it surfaced that McGrath was under his doctor’s orders not to play, apparently because of an underlying heart issue.

As the teams warmed-up, the Electros gaffer spoke with his Longview counterpart, manager Jack Kelly, a longtime acquaintance. “Jack, we’re both about the same age, but I’m a grandfather and you’re not,” McGrath told Kelly. “I’m going to play today and challenge you to play.” Kelly, who had several younger substitutes at the ready, did not take the bait and remained in street clothes.

Of all the prizes McGrath’s many clubs had won, a Northwest championship would be unique. His team’s chances of victory while playing with 10 men were practically nil. His comments regarding his age and health were telling, but no doubt he desperately wanted to give his players the best opportunity to win.

It was a cloudy, breezy but dry day with temperatures rising to the mid-50s at kickoff. The teams were both blessed with speed and technical ability, and play was fast. Twice the Barons forged in front only to be caught by the Electros. Jimmy Bennett brought it back to 2-2 with 10 minutes remaining and with a result within seconds of reality, Longview’s Dave Wishart scored the game-winner.

It was a cloudy, breezy but dry day with temperatures rising to the mid-50s at kickoff. The teams were both blessed with speed and technical ability, and play was fast. Twice the Barons forged in front only to be caught by the Electros. Jimmy Bennett brought it back to 2-2 with 10 minutes remaining and with a result within seconds of reality, Longview’s Dave Wishart scored the game-winner.

At the sound of the final whistle, players from both sides began shaking hands when they were stopped in their tracks. Making his way toward the bench, McGrath suddenly collapsed. Teammates, supporters and physicians in the crowd immediately rushed to his aid. For 15 minutes they tried to revive him. But his last shift had been run, his blue eyes closed for the last time. Billy McGrath, lying in the arena to which he was so fervently devoted, was dead.

Honoring His Service, Keeping Wolves Away

News of McGrath’s demise traveled far faster than the caravan carrying his body back home. Margaret McGrath had been too ill to attend the match; she was recovering from a mild stroke herself. His daughter Christine had lost her young husband a year earlier. McGrath had joined the city parks department staff in recent years; it was evident he was respected and popular beyond the soccer community, although no sector was closer nor was more affected by his sudden loss. Beyond the darkness, gloom fell over Seattle.

State association leaders and players leaguewide, Weston among them, rapidly mobilized the next morning. A day before his burial at Queen Anne Hill’s Mount Pleasant Cemetery, a benefit match had been arranged for five days hence, Easter Sunday. The Timber Barons offered to pay their way north for a Renton rematch with the Electro Dentists. All proceeds would be placed in a trust for the widow McGrath and her family. The following week, the local semipro baseball league would also raise funds during games in South Park.

At Renton’s Liberty Park, McGrath’s friends were everywhere, from greeters and ticket-takers to match officials to, of course, his teammates. The Electros, without their boss, played an inspired game. Although it was an exhibition for the sake of his survivors, it was also a rubber match, the teams having split their two matches. Longview was missing a few regulars and received little mercy. The Seattle squad got a go-ahead goal just before halftime. In the second period they piled on, scoring two more to make it 4-1 on a “splendid shot” from Jimmy McCarthy. The outcome (4-2) delivered the Northwest bragging rights McGrath had craved for his players.

Most importantly, gate proceeds exceeded $1,000 (almost $15,000 today), including more than a hundred tickets sold in Longview. The objective of “keeping the wolves away” from Margaret McGrath had been met. She recovered from her malady to live a long life, although there would soon be more mourning. Her daughter died just 15 months later, at age 20.

Most importantly, gate proceeds exceeded $1,000 (almost $15,000 today), including more than a hundred tickets sold in Longview. The objective of “keeping the wolves away” from Margaret McGrath had been met. She recovered from her malady to live a long life, although there would soon be more mourning. Her daughter died just 15 months later, at age 20.

What Might Have Been

The Electro Dentists’ brand and roster would morph with time. A new manager, Johnny Mair, guided the club known as Dr. Reid’s to five major trophies from 1931-35. For one important fixture, Mair recruited the 44-year-old Kempton, by then a Civic Stadium groundskeeper, and retired Barwick off the sidelines. They did more than survive, Barwick proved crafty and Kempton scored.

In 1950, when the Philadelphia Oldtimers, the founders of what now is known as the National Soccer Hall of Fame, selected its inaugural class, Barney Kempton was duly enshrined. Like McGrath, he was an outstanding player who then contributed as a promoter and state association officer. McGrath’s managing, officiating and interest in developing youth would surely have introduced him to future generations and heightened his profile with each passing year. It well could’ve been him accepting congratulations from fellow inductees in Philadelphia.

Instead, the awards and acclaim evaded him, for he died too soon. Yet in discovering that photograph and discovering the warm yet ultra-competitive human being whom so many felt compelled to salute one final time that Easter Sunday, hopefully Billy McGrath, the fine left back who died with his boots on, has been fleetingly brought back to life through this telling.

Billy, take your bow.

Grateful thanks for assistance from the following: University of Washington Libraries, Seattle Public Library, MOHAI, Don Ruiz and CLM.

A version of this article previously appeared at the Frank MacDonald Blog on April 17, 2020.