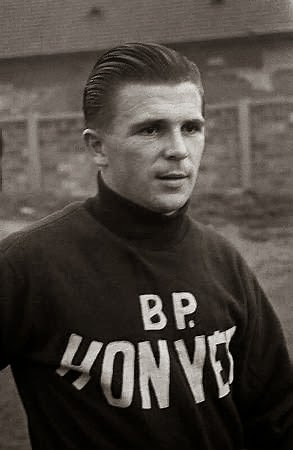

During the 1960s, many people in America were high on soccer. Pundits considered it sport of the future and speculated that soon Americans would be among the world’s elite. One of the many people championing the emergence of professional soccer in the North America was the legendary Hungarian national team and Real Madrid forward Ferenc Puskas. As coach of the Vancouver Royals during the North American Soccer League’s (NASL) inaugural season in 1968, the twentieth century’s most famous Hungarian claimed, “we have the players to take on the world in five years. The Royals will be quite ready to take on Real Madrid, and beat them in five years.” Puskas’ claim could not have been farther from the truth as his team struggled to compete in the fledgling NASL and ceased to exist by the end of the year. Ultimately, Puskas’ lone season managing Vancouver proved rather forgettable and uneventful, although a long forgotten early season game in Washington D.C. provided enough excitement to last the entire season and conceivably defined the Hungarian’s tenure.

Following his illustrious playing career, Puskas jumped right into management and found an opportunity in the incipient United Soccer Association (USA) in 1967. The Galloping Major signed a three-year contract to coach the San Francisco Golden Gate Gales with the intent to manage the club starting in the 1968 season. At the time of Puskas’ signing, the USA imported teams from Europe and South America for its 1967 season in order to get a jump on the rival National Professional Soccer League (NPSL), while also signing coaches and players for the 1968 season. The anticipatory contracts eventually proved problematic after both leagues experienced painful inaugural seasons, and merged to form the NASL in 1968.

Courtesy of www.sportlogos.net

Due to the merger between the USA and the NPSL, many teams relocated or dissolved leaving each city with one professional franchise. Among the list of clubs who ceased operations were Puskas’s Golden Gate Gales. Consequently, Puskas never managed a single game for the Gales. The San Francisco outfit disbanded and united with the existing Vancouver Royals subsequently leaving the Canadian club with two managers, Ferenc Puskas and Bobby Robson. Prior to the creation of the NASL, Vancouver hired Fulham great Robson as player-manager for the 1968 season not anticipating the future acquisition of the Hungarian star. Puskas’ arrival nullified Robson’s position, as the Hungarian became the club’s de facto manager once the two teams merged. Puskas’ appointment left Robson little option but to stay on as an assistant, which the Englishman declined leaving the Royals to Puskas.

Robson’s replacement and eventual departure alienated many of the club’s fans prior to the season leaving renowned Vancouver Sun columnist Jim Kearney to question the move and its effect on the upcoming season’s attendance figures. The club’s haphazard amalgamation coupled with its troublesome managerial situation, caused significant problems regarding Vancouver’s roster. Teams throughout the league scrambled to sign the best available talent prior to the start of the season, the Royals chief among them. Unlike the Chicago Mustangs who had been proactive prior the NASL merger and had a number of players under contract before the start of the season, the Royals were still acquiring players well into the league’s preseason. In fact, Puskas was scouring Europe for a talented striker just five days before the club’s season opener. Vancouver’s lethargic approach to the upcoming season led Kearney to state that the Royals were not ready to compete within the league, which prophetically proved correct by season’s end.

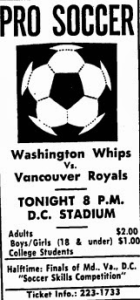

The club’s unorganized approach to the NASL’s inaugural season and Puskas’ lack of managerial experience did not immediately hamper the Royals’ success. Vancouver opened the season with a 4-1 win over the visiting Toronto Falcons, and briefly stood atop the Pacific Division after winning their first three games. The club’s standing among the league’s best changed drastically thereafter. The Houston Stars, led by fellow Hungarian, and former Mighty Magyar teammate, Geza Henni, defeated the Royals 2-1 on April 16 handing Puskas’s his first loss as Vancouver’s manager. Following the Royals first loss, the Canadian side experienced a series of mediocre results with the Royals only winning two of their next eight games, much to the chagrin of Puskas. Vancouver entered a mundane game against the Washington Whips on May 25 third in the Pacific Division with a record of five wins, four losses, and two draws. Up to that point, the Canadian club had only scored seventeen goals highlighting the importance of Puskas’ preseason attempt to sign a legitimate striker, and Kearney’s sober assessment of the club’s chances to compete. The game was anything but dull. It proved to be a turning point in the Royals season, and the highlight of Puskas’ time as the manager of Vancouver.

The Washington Whips played their home games at the seven-year-old D.C. Stadium just miles from the United States Capitol. Washington, like all NASL’s teams, shared its stadium with other sports teams. In addition to the Whips, D.C. Stadium housed Washington’s NFL franchise and Major League Baseball’s Washington Senators. Soccer’s shared tenancy created multiple issues as clubs played on fields of questionable quality and varying dimensions with many still featuring a baseball diamond. It was not uncommon for players and coaches alike to bemoan the league’s playing surfaces. Perhaps the most famous example of the NASL’s dreadful field conditions came in 1975 during Pele’s first match with the Cosmos, when groundskeepers spray painted patches of dirt on Downing Stadium’s field green for the game’s CBS broadcast. Incidentally, the quality of D.C. Stadium’s field played a pivotal role during the Royals visit to Washington, and led to an unexpected outburst by the famed Hungarian.

Prior to the game, Puskas complained that the field was off-center and not rectangular. Despite Puskas’ protestations, the game kicked off as scheduled and began rather routinely. The Royals grabbed a 1-0 lead via a goal from Cheung Chi Wai in the twelfth minute, while Victorio Casa tied the game scoring a goal for the Whips prior to halftime. Washington controlled the second half almost immediately and jumped into a 3-1 lead within eleven minutes after Kaj Hansen converted two penalty kicks. The Royals frantically chased the Whips the rest of the game. Harry Klein, the team’s leading scorer, increased the Royals hope of a comeback scoring a goal in the seventy-ninth minute. The Royals continued to pressure the Whips for the remainder of the game and earned a penalty in the dying seconds of the game. Whips goalkeeper Jack Reilly ultimately saved the penalty shot sealing the Whips 3-2 victory with five seconds remaining. On the face of it, Reilly’s heroic last second save would seem to be the story of the game, but an uncharacteristic tantrum by Puskas stole the following day’s headlines.

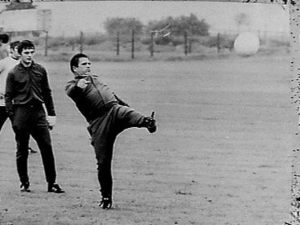

As the game progressed in the Whips favor during the second half, Puskas, perhaps still irritated that the officials allowed the teams to play despite his protestations, entered the field of play. Following a Vancouver foul in the penalty area, Puskas left the Royals bench and made his way towards the spot of the foul against the vehement objections of the officials. Upon entering the eighteen-yard box, Puskas grabbed the ball from one of his players and booted it into the stands. As referee Eddie Pearson approached Puskas, the Hungarian, allegedly, spit towards the referee’s feet drawing an instant ejection from the game. Puskas’ unsavory actions earned instant condemnation from NASL president Dick Walsh resulting in a $300 fine and a two-game suspension. In addition to Puskas’ suspension, Walsh fined Royals defender Peter Dinsdale $50 and levied a five-day suspension on the defender for throwing a punch during the game. While Dick Walsh was busy handing out fines and suspensions, he surprisingly upheld Puskas’ original protest, nullifying the Whips 3-2 victory. In an official report issued on May 31, a Washington survey firm confirmed that the field was in fact not rectangular contributing to Walsh’s decision to nix the result. The two teams were to make up the game and an undetermined date later in the season, while the game defined the Royals season and displayed Puskas’s increasing discontent.

The Hungarian’s eruption and subsequent suspension proved to be the highlight of Puskas’ tenure with Vancouver. Over the course of the next twenty-one games, the Royals would only win seven more games and finish the season at the bottom of the Pacific Division with a record of twelve wins, fifteen losses, and five draws. The suspension was not the only one that Puskas would accrue during the remainder of the season as the Whips game merely provided an outlet for his growing frustration. Throughout the season, Puskas would collect several more suspensions, including one from his club for failing to pay a league levied $200 fine stemming from an infraction the Hungarian committed during the Royals exhibition against Borussia Dortmund. His suspensions led him to manage a game or two from the stands. Ironically, despite Puskas’ upheld protestations, the Whips won the make-up game by a wider margin of 5-3.

Courtesy of Nationaal Archief Fotocollectie Anefo.

In the end, Puskas’ first managerial job was an average affair in a nascent league that did not how to market the star they had in Puskas. The world over, people still remember the Hungarian for his ability on the field rather than lengthy managerial career. The Royals were but Puskas’ first managerial position and conclusively just another name on his resume. Had the NASL not nearly imploded following the 1968 season, perhaps Puskas would have stayed on with the Royals and become one of the league’s greatest managers. Instead, the Royals dissolution forced Puskas to find another job after the NASL shrank from seventeen teams in 1968 to just five clubs in 1969. The Hungarian quickly found another club and joined Deportivo Alavés of Spain the following season. Puskas eventually found success at Panathinaikos guiding the Greek club to the 1970-71 European Cup Final, while Vancouver also found a more permanent club when the Whitecaps represented the city for ten years prior to the collapse of the NASL in 1984.

Notes

In writing this post, my primary source material came from several newspapers. I consulted articles from The Baltimore Sun, The New York Times, The Vancouver Sun, and The Washington Post. As always, I also relied heavily on the wonderful American Soccer History Archives.

A version of the article first appeared on February 23, 2014 at A Moment of Brilliance.