A little more than one hundred years ago, Philadelphia, through the pages of the Philadelphia Inquirer, was at the center of a debate that would draw opinion from across the American soccer scene. At issue was not the relevance of the game in the American sport landscape but the rules of the game itself.

“Should the ‘penalty kick’ in soccer football be eliminated is the question that is now agitating the soccer man,” wrote the Inquirer on Dec. 22, 1912. “Instead of benefiting the offended side it has very often acted as an actual handicap, and instead of inflicting a penalty against the offending side it has very often been a means of robbing the offended side of sure scores.”

The issue would be debated over the next month in the pages of the Inquirer, with some of the leading figures of American soccer weighing in on the topic. In the debate would be reflected a conflict between tradition versus innovation, of conservatism versus progressivism, colored with shades of American exceptionalism.

The heart of the matter

When the Inquirer debate appeared, the rules of the game were still evolving. The penalty kick rule, for example, had first been introduced in 1891 and originally a penalty kick could be taken anywhere along a line 12 yards from the goal line. In 1902, the rule was modified so that a foul committed within an area 18 yards from the goal line and 44 yards wide resulted in the awarding of a penalty kick that would be taken from a spot 12 yards in front of goal.

For the Inquirer, at the heart of the penalty kick issue was the question of fairness. Describing the “meager chances” of converting a penalty kick, the Inquirer observed, “It has been estimated that not more than fifty goals are kicked from one hundred ‘penalty kicks.'” As incredible as this may seem to readers today, it is important to remember the conditions in which the game was played one hundred years ago: Fields were unlikely to have the pool table flatness we are accustomed to seeing and were very likely to be chopped up by the heavy studded boots worn by players. Those players were kicking a bladder-filled laced leather ball that lost any perfect roundness that it might have possessed almost as quickly as it grew in weight from absorbing moisture and mud.

But the penalty kick issue was also imbued with the twin spirits of American exceptionalism and innovation. The Inquirer wrote on Dec. 12, “The game of soccer in this country is played under the rules that exist in England, the home of the pastime that is fast growing in popularity in this country. Great strides have been made in this city and its vicinity in the playing of the finer points of the game. Some very clever players have been developed and some very efficient teams have been built up. During all this time the ‘penalty kick’ rule has been observed simply because it is in the rules that are in vogue in the mother country.” In other words, just because England invented the game didn’t mean the rules couldn’t be improved upon in America.

The Inquirer suggested possible modifications to the penalty kick rule when it opened the debate. Pointing to the “American college game of football,” the Inquirer suggested that the team that had been fouled should have the option to decline the foul, which itself would be predicated on the referee being given the discretion to allow play continue despite a foul being committed or to simply award a goal. The Inquirer illustrated this through the example of a defender using his hands to stop a ball that was otherwise clearly headed for the back of the net. Why should a team that knows it is about to be scored upon not only benefit by saving a goal by committing a foul, argued the Inquirer, and also be given the opportunity to make a save again?

But while the Inquirer may have implied that England’s game could learn a thing or two from the spirit of American innovation, it nevertheless was concerned with protecting the very public school/old boy British values of fair play that informed the formalization of the rules of the game. “If the ‘penalty kick’ rule were abolished it would also result in the game being played in the proper spirit, for it would be the means of eliminating the foul play that is indulged in by some of the players.”

The Inquirer article included examples of incidents in recent games to bolster the view that the rule needed changing. A week later on Dec. 29, the Inquirer reported a fresh incident that had occurred in a third round American Cup match between Philadelphia Hibernian and Newark Caledonian the day before in which a Hibernian penalty kick was saved. “This incident backs up the article that was printed in the Inquirer last Sunday, regarding the penalty kick being eliminated and a goal being awarded direct from a penalty without having to take the kick, which proves that it is at the most only a two-to-one shot that a goal will be scored from a penalty kick.”

The Inquirer debate continues

On Jan. 5, 1913, the Inquirer printed letters from six local and national soccer authorities expressing their opinions on the penalty kick. Locally, J. E. Chambers of the city’s American League believed that the penalty kick rule was in many ways not severe enough and favored its abolition, an opinion also shared by the American League secretary, E. M. Jones. The city’s Allied American Football Association secretary Oliver Hemingway believed the rule should remain and that any fault lay with referees insufficiently knowledgeable of the rules. Referee William Wainman believed the rule should be retained but that the penalty kick should take place from the spot of the foul.

Most important, perhaps, were the opinions expressed by A. N. Beveridge, secretary of the American Football Association (AFA), and Thomas Cahill, secretary of the American Amateur Football Association (AAFA). Disagreements between these two organizations would in a few short months culminate in the founding of the United States of America Foot Ball Association (USFA, today known as the United States Soccer Federation) to supplant the AFA as the country’s preeminent governing body for soccer.

Beveridge wrote, “Hoping the penalty kick will still be in vogue, but I would like to see it modified so that it would place both the defending and offending teams on more equal basis.”

Cahill, who in 1912 had traveled to Stockholm to gain support from FIFA for the AAFA over the AFA, was unequivocal: “I consider the penalty kick absolutely essential for the good of the game, and can see no good reason why it should either be changed or eliminated.” Repeatedly praising “the International Board of Great Britain, the recognized and official rule creators of soccer,” today known as the International Association Football Board, Cahill concluded, “Instead of tampering with the rules, let them remain as they are at present, and direct all efforts to educate the players in the proper interpretation of the rules, secure competent referees, and then sustain them in their rulings on the field.”

The Inquirer kept interest in the debate alive by mentioning it in other soccer articles. A report on Jan. 8 about a meeting at the newspaper’s offices that resulted in the founding of the city’s new United League noted that Phillip Bishop, described as “one of the best versed men on the soccer game in this country,” had given a “natty speech” that included mention of the penalty kick debate. “He stated that it would result in the enlightening of players and spectators on the penalty kick law even if it did not in time result in some alteration being made in the rule.”

Conservatives vs progressives

The Inquirer continued to publish series of letters on the debate. Local soccer luminaries such as John B. Farrell, president of the city’s Allied American Football Association, and Benjamin Groves, president of the city’s professional Pennsylvania League, continued to weigh in on the topic. But views from some of the eminent names of the wider American soccer landscape also continued to be heard. Andrew M. Brown, president of the AFA, Charles C. Pickford, president of the New York Footballers Protective Association, and Ed Waldron, president of the Referees Association, favored retaining the penalty kick rule as is, as did Dr. A. Murray, president of the St. Louis Soccer Football League.

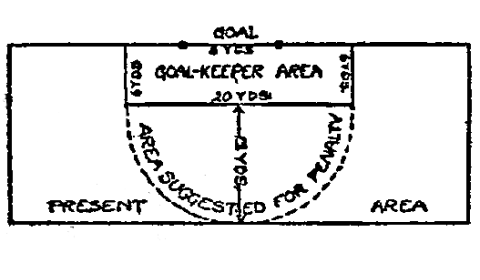

Thomas T. Adams, manager of the West Hudsons, and John Lone, secretary of the National Association Football League, favored changing the rule with Lone providing a diagram suggesting how the penalty area could be re-defined with “a semi-circle from the outside lines of the goalkeeper’s area to a point 18 yards from the goal line.”

Even Fred H. Milne, the former England international who had emigrated to the US after captaining the Pilgrims on two American tours in 1905 and 1909 — tours that had done much to further interest in the game — contributed his support to retaining the penalty kick rule. “I strongly believe that the Penalty Kick rule is of great value,” Milne wrote before questioning the factual basis of the Inquirer’s original argument for abolishing the rule. “I should hesitate very much before saying that 50 per cent of the Penalty Kicks taken are not converted into goals—on the contrary, well over 75 per cent are converted.” And where the Inquirer had looked to American college football as an inspiration, in gridiron football Milne saw a warning: “Do not let soccer in this country be trifled with, especially in its infancy or it may in time come to meet the same fate as English Rugby did out here.”

On Jan. 12, echoing the social and political themes of the day, the Inquirer characterized the debate as one between conservatives and progressives.

It is a noticeable fact that those who are opposed to any change being made in the “Penalty Kick” rule, are very largely influenced by the law-making by the International Board. What the Board has read into the rules and what has proven good enough for other countries is in their opinion good enough for America, which includes Philadelphia and other places where soccer thrives.

There are many progressives, however, who favor changes in the rules and who are inclined to the belief when it should be changed not withstanding that England and other countries where soccer has been played for a much longer time than it has here have found the rule good enough for them.

The Inquirer noted that the progressives were not of one mind, with suggestions ranging from abolishing of the rule altogether, to modifications of where a penalty kick should be taken from, to modifications of the penalty area itself.

“Penalty kick here to stay”

Given the variety of suggestions about how the penalty kick rule might be changed, it is no surprise that the title of an article in the Inquirer declared on Jan. 19, “Penalty kick here to stay: Few Desire It Eliminated But Many Suggest That Rule Be Modified.” Lest there be any concern about Americans bowing to a foreign rule-making body, the Inquirer made clear that those who thought the International Board should govern rule changes was not a case of inferiors kowtowing to their betters.

The great majority who hold to that are not ruled by the fetish of what is deemed wise by the parent body should be accepted as the best that can be done, but rather because they believe that long experience in playing the game and making laws to govern it has fitted the International Board to serve for the best interest of the sport. The game of soccer, it is claimed, is in its infancy here and until we, America, learn the game as well as it has been learned in England we should not attempt to improve upon its laws and rules.

But, the Inquirer warned, as the game grew here, America would soon gain the experience to play the game according to its own rules.

[T]he time does not seem far distant when America will make some changes in the game to meet with the best conception of the sport as it is held here. The trend of opinion, with few exceptions, seems to point in that direction. America will have no doubt sometime in the future will have its own ruling body and will cut loose from traditions brought from England by the very many skillful players now engaged in the sport here and whose skill and enthusiasm have brought the game into fast growing popularity with native-born Americans.

Nevertheless, mindful of the concerns voiced by Milne, the Inquirer was aware that this spirit of innovation could result in less than desirable outcomes for some sport fans. “There are some who already sound a warning…They point with regret to Rugby football, from which the present American college game of football has evolved. To change the game of soccer from the way it has been played for half a century or more should be considered a crime.”

Whether motivated by a more neutral impulse to improve the game or by more arrogant and/or misguided efforts to “Americanize” the sport in order to make it more “attractive” to an American audience, American soccer would continue to be littered with attempts at rule innovations. Some of these rule changes persist, notably at the college level. But with the ongoing growth of soccer has come the understanding that the base of soccer fans wants the game to be played according to the rules followed by international soccer. Now, the American impulse toward innovation is reflected by what is perhaps a more realistic understanding of US soccer’s place in the world’s game and is expressed by a willingness to adopt innovations such as goal-line technology rather than through implementing new rules or advocating for the elimination of long-standing rules.

Still, for a month or so one hundred years ago, Philadelphia was at the center of a national soccer debate that was focused not on the relevance or importance of the game, but on the rules of the game itself. And that’s not a bad thing at all.

A version of this article first appeared at the Philly Soccer Page on January 9, 2013.

Great stuff. I always enjoy anything that runs counter to the idea that Americans only started taking an interest in soccer about 20 years ago.