Many thanks to Brian Bunk, Kurt Rausch, and Roger Allaway for the insight and comments while I was working on this article.

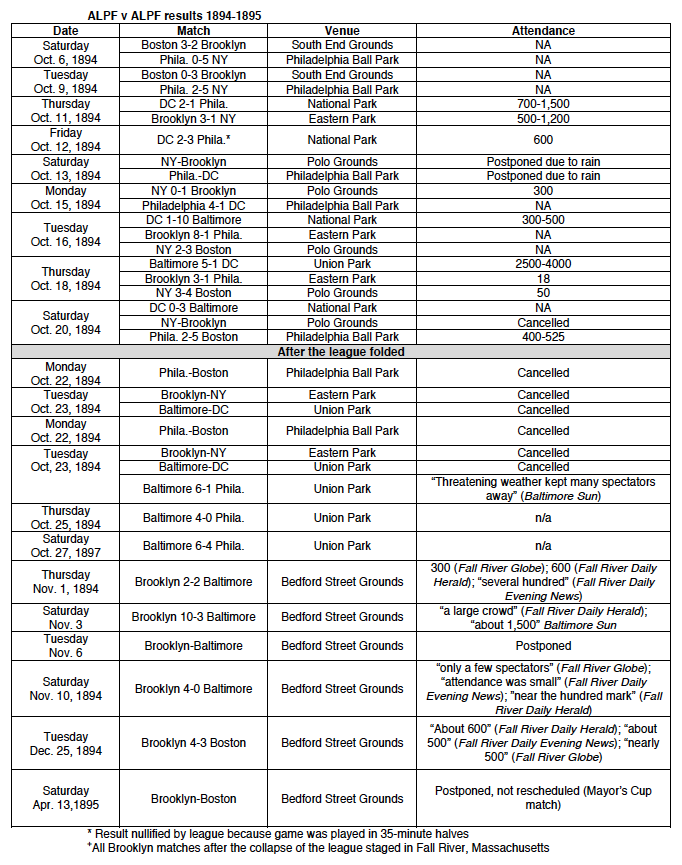

After only two weeks of play and sixteen games, the American League of Professional Football Clubs (ALPF) collapsed. Comprised of six teams backed by baseball’s National League, the ALPF’s last games were played on October 20, 1894. League officials had actually decided to pull the plug on the ALPF on October 18 but a statement did not appear in newspapers until October 21.[1] J. Earle Wagner, the owner of the Washington D.C. team, said the league would reorganize “on somewhat different lines” over the winter to be “ready to go at the thing for keeps in the spring.”[2]

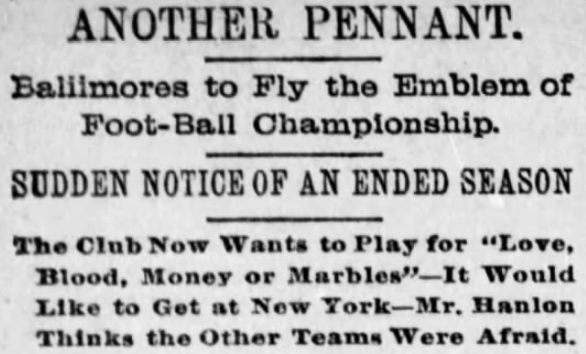

The decision to end the season was followed by striking claims from the Baltimore team, whose importation of several professional players from Britain was a burgeoning controversy of such scope as to attract the attention of the United States Treasury Department. Baltimore had been late to begin play; its first game took place only two days before the decision was made to end the season.[3] Baltimore’s National League baseball team had finished the 1894 season in first place to capture the pennant weeks before only to be swept by second-place New York in the postseason Temple Cup series, which finished on October 8. It was the belief of Baltimore manager Ned Hanlon and his team that the reason other ALPF clubs “gave up the ghost” and ended the season early was “because they believed that they had no chance to defeat Baltimore.” Hanlon explained,

We entered the league in good faith and intended to play the season out, however long it might have lasted. We showed this by spending twice as much money as any other city to secure the best professional foot-ball eleven we could get, and now that we have demonstrated our superiority New York and the other cities try to avoid defeat at our hands by ending the season…New York and Brooklyn had undoubtedly much to do with bringing the season to a close. Baltimore had already won the base-ball pennant and of course it would never do for these great and enterprising towns to be again eclipsed by the Monument City. While the Baltimores did not play as many games as did the other clubs, yet they did not lose a game.[4]

The team’s unbeaten record in league play — three wins from three games — came against one opponent, Washington D.C., a team whose hapless record was only marginally better than that of Philadelphia, the worst team in the league. As the Baltimore Sun argued, “Having lost no games the Baltimores’ percentage is 1.00. Theirs is the only club in the league with this record.”[5] The report included a league table based on winning percentage. According to Hanlon, who managed both Baltimore’s baseball and soccer team, “The foot-ball pennant must surely be raised in Baltimore…while the base-ball pennant will float from one end of the grand stand.”[6]

But earlier reports on the league suggested the team with the most wins would be the champion. A report in March soon after the league was first announced said, “rules will be adopted conforming as nearly as possible with the English rules.”[7] In June the league announced the “American Association Football rules of ‘94” — presumably the rules of the American Football Association (AFA), organizer of the American Cup tournament – would “govern all contests.”[8] In August, league secretary and secretary of the New York National League baseball team George E. Stackhouse said the ALPF’s constitution was “built on the same lines as that of the National Base Ball League.”[9] In each of these references — the FA in England, the AFA, the NL — the team with the most wins is the champion. No mention is made of winning percentage determining a champion.

The focus in Baltimore on New York, which had a losing record in ALPF play after winning two games and losing four, is telling: Hanlon clearly hadn’t gotten over the Temple Cup humiliation. Mentioning Brooklyn made more sense. With a record of five wins and only one loss, Brooklyn was arguably the best team in the ALPF. Boston, the team with the second-most wins with four wins and one loss, apparently wasn’t great and enterprising enough to be in on Hanlon’s undoubted conspiracy.

After the abrupt closing of the ALPF season, Baltimore captain A.W. Stewart, who had been authorized by Hanlon to sign Detroit-based players for the team, said the team would not disband for two weeks. Having “caught the Baltimore Spirit,” Stewart joined Hanlon in suggesting other ALPF teams were afraid to face Baltimore, asserting the team’s 10-1 win over Washington D.C. in its first game “opened the eyes of New York and the others.” He then declared the team’s willingness to defend its claim to being the “Champion Foot-Ball Club of the United States” against any challenger and proposed a series of games against New York and Brooklyn to settle the matter.[10]

But Philadelphia manager and league founder Arthur Irwin was the first to challenge Baltimore.

Baltimore hosts Philadelphia

Irwin’s Philadelphia ALPF team was the worst in the league, managing only one win in seven outings, and that against Washington D.C. Philadelphia had actually played nine league games, recording a 3-2 road win over Washington on October 12, 1894, that was later nullified by the league because the game had been played over 30-minute halves rather than the regulation 45-minute halves.[11] One factor in the Philadelphia ALPF team’s poor record was surely related to the competition to sign players with the Philadelphia team in the ALPF’s professional league rival, the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF). Managed by Clement Beecroft, the founder of the AAPF, the Philadelphia AAPF team was the leader of its league. One hometown paper of its fiercest competitor, the Paterson AAPF team, described Beecroft’s aggregation as “without a doubt the strongest team in America.”[12]

On October 23, Irwin’s Philadelphia team traveled to Baltimore’s Union Park for the first game of a three-game series. If for Baltimore the series was an opportunity to buttress its claim to being the ALPF champion, for Irwin it was probably simply a chance to make some money. After all, the league had committed to paying its players through November 1 so why not take the opportunity for a portion of more gate receipts?[13]

In that first game after the ALPF’s collapse, Philadelphia quickly demonstrated it was no match for Baltimore’s quality, and by halftime, the home team was winning 3-1. At the final whistle, the scoreline was 6-1.[14] The teams met again on October 25. The highlight of the game was the appearance in goal of Charlie Reilly, who played third base for Philadelphia’s National League baseball team. One report said Reilly “had plenty to do, and he did it so successfully that the spectators applauded him.”[15] Nevertheless, Baltimore finished with a 4-0 victory. The series concluded at Union Park on October 27 with Baltimore maintaining its unbeaten record after a 6-4 victory.[16] It was the last time the Baltimore ALPF team played at its home stadium. It was also the last time Baltimore would win a game.

Baltimore goes to Fall River

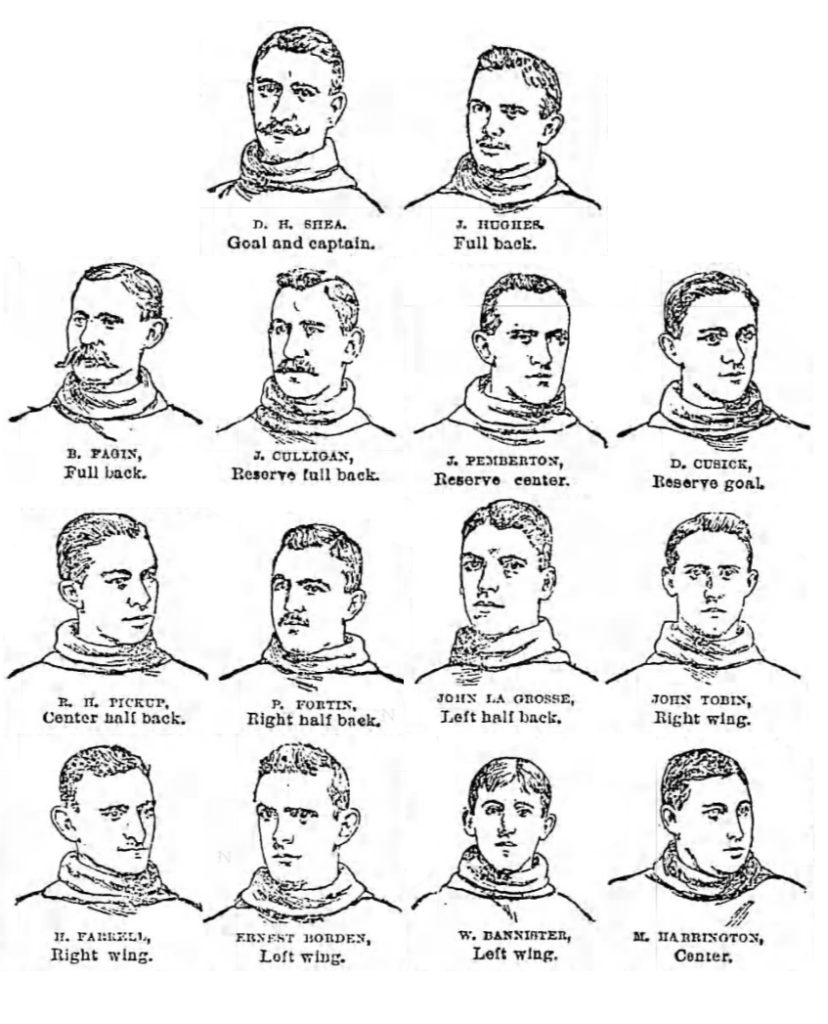

Baltimore’s team was made up of native- and Scottish-born players brought in from the Detroit Association Football Club as well as players imported directly from England. Brooklyn’s team, like Boston’s, was signed from clubs in Fall River, Massachusetts, and Pawtucket, Rhode Island, together one of the early and most fertile hotbeds of American soccer. Brooklyn’s players principally came from the Rovers and East End clubs and most were native-born, along with two French Canadians and one each from England and Scotland.[17] Several members had experience on championship sides in the AFA’s American Cup tournament. Team captain and goalkeeper Dennis Shea, a native of Fall River, had joined the Canadian-based side that toured Britain in 1891. Fullback Barney Fagan won the 1886-87 Scottish Cup with Hibernian before immigrating to America where he captained the Rovers side that won the 1888-89 American Cup championship and included Shea.[18]

After the ALPF announced it’s demise, the Brooklyn players returned home to Fall River on October 21, “in no wise discouraged” even if “the crash was totally unexpected by them.”[19] This after a newspaper a report only three days before had described the poor attendance for Brooklyn’s home win over Philadelphia — “18 persons paid their way into the grounds” — and that the Brooklyn players were “anxious about their pay.”[20] Nevertheless, the team decided to stay together. Management in Brooklyn even allowed the players “to retain their suits” provided that “if they play together again this season it shall be under the name of the Brooklyns.”[21] Fagan said exhibition games would be arranged while it was reported Shea was “laying plans” for the team to tour Canada.[22] The decision to keep the team together made sense. The AFA had banned all players who had joined ALPF and AAPF clubs from participating in the American Cup. The New England League, home to the clubs in Fall River and Pawtucket from which so many of the players on both the Brooklyn and Boston rosters came, had established a “blacklist” to prevent the ALPF professionals from being signed by clubs under its jurisdiction. As for the players themselves, most were “now working” and preferred not to join local clubs “as they have hope that they will be in the big cities again in the spring” with a reorganized ALPF.[23] There was even talk of ALPF night games being played in the summer “under the glare of electric lights.”[24]

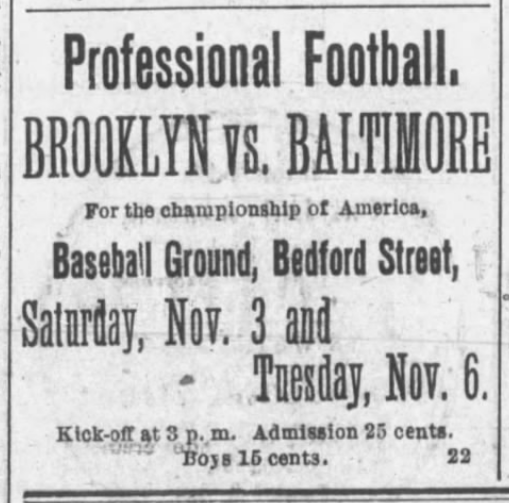

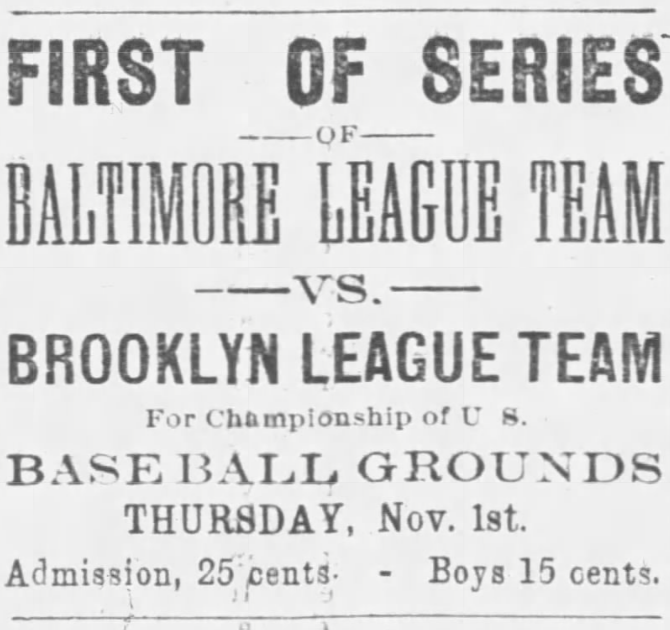

On October 24, the Fall River Daily Globe reported Baltimore’s Hanlon had asked the Brooklyns for a series of games “for the championship of the country” and that the Brooklyns “were agreeable to the scheme.”[25] On October 28, the day after Baltimore’s final game against Philadelphia, Shea said he was working to arrange three games in Fall River, and one in Pawtucket, before a final three-game series in Baltimore.[26] The next day, Shea confirmed the team had secured the Bedford Street Baseball Grounds to host Baltimore, who arrived in Fall River the following morning.[27] The Baltimore team that made the trip north was slightly different than the one that had faced Washington and Philadelphia. The forward Barkey had been released due to “youth and lack of seasoning.” After the completion of their three-game home series, Baltimore signed inside left wing J. Cochran from Philadelphia.[28] Also with Baltimore was Fernley, a halfback, who had not appeared in ALPF league play but had been in the lineup against Philadelphia. The “series for the championship of America” was set to commence on November 1.[29]

According to the Baltimore Sun, correspondence between the team captains had created “a spicy state of rivalry.” Stewart believed Baltimore was the league champion thanks to “the percentage rating” while Shea believed Brooklyn was the champion because it had won more games.[30] (In a letter to the Fall River Daily Globe dated October 19 and published on October 20, Shea included a league table based on two points for a win and one point for a draw that had Brooklyn on top and Boston in second place. Baltimore, at that point having played two games, was listed in fourth place.[31]) Indeed, so convinced was Shea of his team’s superiority he informed Stewart that “two Fall River Men” were willing to bet “from $500 to $1,000” on the outcome of the series “if there is any Baltimore money seeking investment.”[32] That’s the equivalent of a bet of about $15,000 to $30,000 in today’s value.

While it is unclear if there were any takers, one local report said 600 spectators paid 25 cents to see the first meeting between the clubs, a gate of $150, or nearly $4,500 today.[33] Another local report put the crowd at 300, probably a more accurate number considering the game kicked off at 3 pm on a Thursday when most fans were still at work.[34] Both reports clearly described the contest as the first game of a series for the American championship.

The Brooklyn players wore black uniforms with white trim while Baltimore wore black jerseys with orange trim and white breeches and, according to one report, “It is doubtful if a more scientific game was ever played.”[35] This despite the game being played “in a gale of wind.”[36] Brooklyn opened the scoring after only five minutes of play and later missed a penalty kick attempt while Baltimore equalized before the end of the first half. With darkness falling, the game quickly resumed and after twenty minutes of play, Baltimore took the lead. About ten minutes before the final whistle, Brooklyn equalized and the game finished as a 2-2 draw.

One report on the game made much of the “Scotlanders” on the Baltimore team “who know what it is to line up against some of the best football talent in the world,” adding a more appropriate title for the series of games would be “‘America vs. Scotland.’”[37] Interestingly, the sympathies of the Fall River fans seem to have shifted toward the visiting team over the course of the game. While Brooklyn played “a dirty game,” Baltimore’s play was described as “clean and gentlemanly” with no “roughness.”[38] To the Baltimore players, it seemed that the referee “was doing all he could to give Brooklyn the game.”[39] The short passing style and dribbling skills of the Baltimore team were praised and delighted the crowd. One report noted betting for the second game of the series was now “in favor of Baltimore.” Perhaps more importantly for the players, now dependent on gate receipts for their pay, not to mention the bookmakers, the report concluded, “With good weather the crowd will be well up into the thousands.”[40]

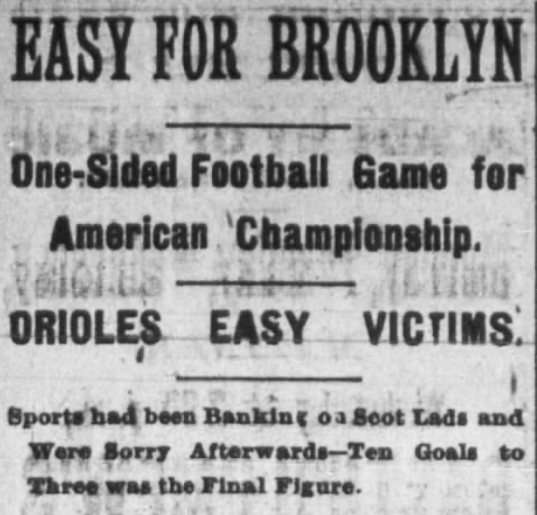

The weather turned out to be “all that could be desired” when the teams met for the second game of the series on Saturday, November 3, even if the grounds were “a trifle soft.” One local report described “a large crowd” was on hand to see the game while a Baltimore report put the number of spectators at “about 1,500.”[41] Whatever the actual attendance, the hopes of those expecting a Baltimore victory were quickly dashed; by the end of the first half, Brooklyn was winning 5-1. At the final whistle, Brooklyn were 10-3 victors, a scoreline reminiscent of the thrashing Baltimore had given Washington. “What was the matter with the Baltimores,” a local report wondered before concluding, “It must be confessed they were never in the game.”[42]

The third game in the series was scheduled for Tuesday, November 6 but a report the day before said the contest had been postponed until the following Saturday.[43] No reason for the scheduling move was reported but presumably, it was done to maximize the gate. On November 8, the Baltimore team traveled to Pawtucket for a match against a picked side.[44] A previous report had described the scheduling of a three-game series in Pawtucket.[45] This was understandable since the players were in New England to make money as well as justify their championship claims. Why be idle when money could be made playing local sides other than Brooklyn? But idle they remained “owing to the bad weather” and it appears Baltimore never played a match in Pawtucket.[46]

Threatening weather hung over the scene when Brooklyn and Baltimore met for their final encounter on November 10, which attracted “only a few spectators.”[47] Once again, Brooklyn was the superior side, quickly scoring the first goal of the game after five minutes of play. By the end of the first half, Brooklyn had scored three unanswered goals. During the second half, “a spectator became engaged in a wrangle with Stewart,” and a fight was averted only by the intervention of the referee, who also happened to be a local police officer.[48] Baltimore was held scoreless and at the end of play Brooklyn were the 4-0 winners in the “comparatively easy contest.” Concluded one report, “The Baltimores were outplayed at every point.”[49] With their winning percentage now at 72.22% compared to Brooklyn’s 83.33%, the Baltimore Sun did not report the match result. The return of the team to Baltimore a few days later merited only a one-sentence mention in the Sun.[50]

How did Baltimore go so quickly from dominating to losing? As has been described, their early dominance came against the two worst ALPF teams, Washington D.C. and Philadelphia. The gale-like conditions in the first game in Fall River favored the short passing style of Baltimore while inhibiting Brooklyn, who played more of an aerial game of dumping crosses into the box. Said one report, “As it was a windy day, this is where they threw the game away.”[51] In the second contest, while the improvement in Brooklyn’s passing game was a factor in their decisive victory, superior speed and physical play were more important. As one report described, “When it came to close scrimmages the ‘ginger’ of the Brooklyn boys counted, and so knocked the championship hopes of their antagonists pretty high.”[52] By the third game, Baltimore had been idle for a week with bad weather ending hopes to make money from other exhibition games. After suffering such a crushing defeat, and with additional money-making opportunities drenched, it’s easy to imagine they were demoralized and simply wanted the series to be over.

The games in Fall River between the Brooklyn and Baltimore ALPF teams were supposed to be just the start of a series to settle the question of who was the national champion and over the next week, Fall River newspapers reported on arrangements underway for the Brooklyns to travel to the Monument City, including the possibility of a series of games over the week of Thanksgiving.[53] For the Brooklyn players, confident they were the best ALPF team, a trip south was mainly about making money and their prime concern was receiving a guarantee to cover expenses. The Fall River Daily Globe reported,

They have shown beyond a shadow of doubt that they are a better team than the Southerners, and they have little glory to gain by winning the rest of the games. The players would like to take the trip, as they think, judging from the attendance at former games in Baltimore, that it would be profitable.[54]

To this point, Brooklyn had only the word of Baltimore captain A.W. Stewart that the team would be paid but that wasn’t enough. Meanwhile, other reports described Brooklyn captain Dennis Shea’s efforts to arrange a tour for his team in England the following spring.[55]

As late as November 24, a report appeared in a Fall River newspaper on the possibility of finishing the championship series in Baltimore.[56] But the Baltimore team was already finished. On November 21, the Baltimore Sun reported the team had disbanded, noting “their engagement with the Baltimore management” ended when the league abandoned the season, the team continuing since then “on the co-operative plan.” Baltimore manager Hanlon “paid the men a sufficient sum to take them to their homes in comfort and gave each a ticket to New York.” As for the players who had been imported from England, Hanlon “paid their passage on the steamship.”[57] No more was there talk of a “foot-ball pennant” rising above Union Park. If there was an ALPF champion it was Brooklyn.

Brooklyn versus Boston, Boston players get their due

Following their success against Baltimore, Brooklyn booked games against local clubs. But because other established teams were engaged in league or American Cup play on Saturdays — Sunday games were not allowed — holidays were generally the only days open for local sides to face them. The Brooklyns scheduled a home match against Fall River Rovers for the morning of Thanksgiving, after which they were to travel a little over twenty miles to face Rhode Island’s Pawtucket Free Wanderers on Thanksgiving afternoon. In the event, the home match against the Rovers was canceled because “few spectators” showed up to see the game. The Free Wanderers had themselves scheduled a doubleheader for Thanksgiving, winning 4-1 in a New England League contest against the Pawtucket YMCA team in the morning. That afternoon, “a large crowd” was on hand to see Brooklyn defeat the home side, 5-1.[58] The teams faced off again in Pawtucket on December 22 in front of “a large crowd” in what was supposed to be another friendly but instead looked like “a desperate cup tie” during which “more than once the police had quite a job in clearing the field” of encroaching spectators.[59] Just before full time Brooklyn scored to finish 3-2 winners.

But another local team was an inevitable attraction: the Boston ALPF team. Like the Brooklyn team, the Boston roster was largely composed of players from “Fall River and its vicinity,” particularly from the Fall River Olympics.[60] And like the Brooklyn team, its roster was replete with past American Cup winners. Goalkeeper James Irving and left-winger John Sunderland had each won the championship three times; Patrick Farrell also had an American Cup championship under his belt.[61] Before the collapse of the ALPF, Boston had played one fewer game than Brooklyn for a record of four wins and one loss, making them the second-best team in the league in terms of straight standings. Indeed, each team’s only loss in ALPF play had come against the other.

But if the Brooklyn players were satisfied with their treatment by the Brooklyn management after the end of the league, this was not the case for the Boston players. While the league had pledged to pay its players through November 1, reports soon emerged that the Boston players believed they were entitled to be paid for the entire length of the contracts they had signed, which covered through the end of the year.[62] Remarking upon the “considerable dissatisfaction” of the Boston players, a later report observed they also had not been paid a bonus as had “generally been the case” with other teams when the season ended prematurely; the Brooklyn players, for example, had each received a bonus of fifty dollars, equivalent to approximately $1,500 today. Legal options were being considered “to bring the Boston magnates to terms.”[63] One unnamed player soon hired a lawyer to represent him in a lawsuit for unpaid salary.[64] Another report from a Fall River newspaper said locally based Boston players would soon travel to Boston to “demand salary according to their contract.”[65] In March 1895, the Fall River Daily Herald reported that Boston halfback and captain Arthur Puleston had filed “the first of a series” of lawsuits against the Boston National League team to recover wages due, with a later report saying the lawsuits of Puleston “and other players” would be tried in April. The latter report also alleged the Boston baseball team had canceled a planned exhibition game against the Fall River baseball team before the opening of the National League season “because it was feared the gate receipts would be attached by the football men.”[66] In December 1895, one week before Christmas, the Fall River Daily Evening News reported a “compromise has been effected [sic]” between the players and the Boston management.[67] Puleston and one other player, John Sunderland, would receive $65, the equivalent of about $1,970 today. Eight other players each received $45, or about $1,362.

On Christmas Day 1894, Brooklyn hosted Boston at the Bedford Street Grounds. Since the collapse of the ALPF, Brooklyn had played five games. The Boston team had last played together on October 20 when they defeated Philadelphia 5-2 in their final ALPF league game. Despite “the doubtful weather,” 500-600 spectators were on hand to “to witness a really first class game.”[68] Boston was doubly handicapped: not only had the team not played a match in more than two months, their lineup included “several substitutes;” four players who had been in ALPF play for Boston, two of whom appear to have been signed from England and Scotland, were no longer with the team.[69] Brooklyn was the first to score but in a “surprisingly short time” Boston equalized before taking a 2-1 lead. Just before the end of the first half, Brooklyn scored again to put the teams back on level terms. In the second half, Brooklyn scored two goals in quick succession before Boston managed to tally one more to make it 4-3, after which “spectators then began to crowd the field and interfered greatly with the men.”[70] At some point in the second half one of the Brooklyn players retired with a knee injury, leaving his team shorthanded. Despite some “fast and furious” play at the final whistle, the score remained 4-3 and Brooklyn were the winners. The Fall River Globe praised the Boston team, writing they “deserve great credit” for their performance, doing “very well for men who have not played together for some time.”[71]

The Brooklyn-Boston match came only a few days after the National League announced the “unhappy and unprofitable…experiment” that was the ALPF “will not be repeated,” ending the players’ hopes of returning to the big cities to ply their trade in the spring.[72] If the teams were to stay together it would be to face local sides.

Brooklyn and Boston in the Mayor’s Cup

A few days after the Christmas Day match the Brooklyn and Boston teams were invited to participate in the Mayor’s Cup, a local charity tournament.[73] Newspaper reports of Brooklyn scheduling games against local opponents continued through the winter months of 1895. On January 13, 1895, Fall River’s East End team hosted Brooklyn at the County Street Grounds so that the East End players could have a warm-up game before facing the Pawtucket YMCA team the following week in the American Cup tournament. Brooklyn won 6-4 in front of a “handful of spectators.”[74] But the game was an exception as weeks of bad weather resulted in postponement after postponement, wreaking havoc on both the New England League and American Cup schedule, not to mention exhibition games.[75] Indeed, the East End-YMCA American Cup match wasn’t played for nearly two months. [76]

In early March, the Fall River Globe reported that both Brooklyn and Boston would appear in the Mayor’s Cup tournament, with Boston representing the East End team in the series, along with the Olympics “and probably the Rovers.”[77] But when the organizing committee met two days after that report it was decided the four teams admitted into the competition would be Brooklyn, East End, Olympics, and Rovers. Nine players remaining from Boston’s professional ALPF roster would be distributed between the Rovers and East End “to strengthen those teams so as to place all clubs on as nearly an equal footing as possible…providing these players are willing to unite with the club they are assigned to.”[78] Brooklyn would use the Rovers’ grounds as their home field with the nine-game series scheduled to start with East End hosting Brooklyn on March 23.

Remarkably, given the months of poor weather, the game at East End’s County Street Grounds was played on its scheduled date with about 500 spectators in attendance. Unfortunately for East End two of the four Boston players allocated to them by the Mayor’s Cup organizers were unavailable, including their goalkeeper James Irving, and Brooklyn won easily 6-2.[79] Nevertheless, the general opinion was that continued good weather and decent games “would revive interest in the sport” after such a trying winter.[80] But the next match date, March 30, which was to feature Rovers-Brooklyn and East End-Olympics, turned out to be another disappointment. The Rovers-Brooklyn game was postponed due to high winds and “poor attendance” while East End failed to show up to face the Olympics; East End again failed to appear for its April 6 match against the Rovers and soon after dropped out of the competition.[81] Meanwhile, Brooklyn defeated Olympics 3-1 at the South End Grounds. Attendance was “very poor,” with fewer than fifty people paying admission to the game. With Brooklyn content to sit back and defend after scoring all of their goals in the first half, “the handful of spectators was glad when it was over.“[82]

Before East End dropped out of the Mayor’s Cup the Boston players met and decided to challenge Brooklyn for a series of three games, the first to be played in Fall River, the second in Pawtucket, with a third game to be played if necessary to break a tie.[83] But with East End out of the Mayor’s Cup, Boston was back in the tournament to take their place and scheduled to face Brooklyn on April 13. Yet, once again, bad weather in the form of heavy rain forced that game to be postponed, as was the match between Olympics and Rovers scheduled for the same day. The Fall River Globe reported, “The outlook for football in this city is now more discouraging than ever and it is doubtful if the scheduled games will be finished.” Fans were tired of showing up for games only for players not to appear. Players were tired of leaving work to play for nothing. The opening of the baseball season all but insured flagging interest in soccer would be directed elsewhere. Observed the Globe, “[I]t is plainly evident that prospects of raising the sport to its old standard of popularity are anything but bright.”[84]

Brooklyn was scheduled to host Olympics on April 19, a rare opportunity for a Friday match thanks to the Lexington Day holiday but they called off the game the day before: “The Brooklyn players are not pleased with the prospects of kicking for nothing and are satisfied that, with a baseball game going on s short distance from the grounds, there would be no attendance.”[85] With the teams losing money “on account of the slim attendance” it was finally announced in late May that the Mayor’s Cup had been suspended until the next season, “when it is hoped that something like the former interest will be revived.”[86]

Former ALPF professionals in league and American Cup play

Soccer in Fall River was in a sorry state as spring turned to summer in 1895. In May, the New England League called off the season rather than try to finish the large number of postponed games and in June the Olympics were declared champions based upon their superior record in the uncompleted schedule.[87] Pawtucket Free Wanderers, finalists in the American Cup tournament along with the Caledonians of Newark, New Jersey, elected to host the tournament final on the Fall River Rovers’ grounds on June 1. Despite being the favorites, the Free Wanderers were routed by the Caledonians, who easily won 4-0.[88] It was the first time in eight years that a team from Fall River or Pawtucket was not American Cup champions. Fewer than two hundred spectators showed up for the final, “many of whom were from Pawtucket,” the Fall River Daily Globe observed, “a fact which shows conclusively that for a time at least, football is practically dead in this city.”[89] Wrote the Fall River Daily Evening News, “Football has sunk to a low ebb when the final game for the American cup attracts less than 200 spectators,” adding the Caledonians “will get a set of gold medals to indicate their possession of the championship of a very decrepit football association if there is money enough in its treasury to buy them.”[90]

The Brooklyn and Boston teams quietly disbanded after the suspension of the Mayor’s Cup. The New England League’s blacklist preventing former ALPF players from joining local sides also was quietly dropped. Perhaps, given the precarious state of the game in Fall River, it was thought best to do whatever was possible to boost interest.[91] In September ahead of the start of the new season, the league decided to allocate the former professionals of the Brooklyn and Boston ALPF teams among its roster of clubs, with the Olympics receiving six players and the Rovers receiving seven.[92] New Bedford was also to receive an allocation but when East End joined the league in their stead it received the players.[93] Soon after the allocation of players was announced, former Brooklyn captain Dennis Shea was elected vice president of the league.[94]

All of the New England League clubs entered the 1895-96 American Cup.[95] For the clubs, the main question now was the eligibility of the former ALPF professionals to participate in the tournament from which the AFA had banned them in September 1894.[96] At the time, the AFA ban had “caused much feeling” among players in Fall River, who were “incensed” by the announcement, with some threatening to “reveal some of the doings of the men who compose the league committees.”[97] In response to the AFA’s announcement, Shea wrote a letter published in the Fall River Daily Globe in which he said local delegates who were instrumental in enacting the ban had “put their foot into something from which they will be glad to pull out before long,” adding, “I don’t think it bothers the players whether or not they are blacklisted.” Whatever the truthfulness of the latter statement, Shea further criticized the AFA as a stagnating organization that was “in almost the same condition as when it started.” Rather than banning players, the AFA should instead look “more to the interests of the game” and “be only too glad to see others grasp the links they have failed to fetter.”[98]

Shea’s displeasure with the AFA’s ban is understandable but he wasn’t just a player reacting to the AFA exercising its authority; he was intimately connected with the ALPF. Shea had been invited to the ALPF’s final organizational meeting, which took place in New York City on August 14, 1894.[99] A little more than a week later, Brooklyn president Charles Byrne visited Fall River to begin signing players for his team. In addition to signing Shea as the team’s captain, Byrne authorized the goalkeeper to sign fifteen players.[100] He soon had enough of a roster together to field a side against the Fall River Rovers on Labor Day — played for a purse of $100 — winning 6-3 in front of 1,000 spectators.[101] By the end of August, Shea was also signing players for the Boston ALPF team.[102] One player, John Sunderland, reportedly signed with Boston for $80 a month — equivalent to about $2,375 dollars today — plus expenses, although a later report said news of such salary figures was “being accepted with a grain of salt.”[103]

A week after the AFA announced its ban, the New England League also voted to ban players who signed with ALPF clubs “as the absence of the stars has well-nigh destroyed interest in the game for the present.” The consensus among league administrators was that the ALPF would “last for one season at the longest, and that players who have been tempted by the offers will eventually find themselves out in the cold,” a rather prophetic reading of what was to come.[104]

Curiously, before the start of the 1895-96 season, no discussion of AFA eligibility appeared in Fall River newspapers. But in December 1895, AFA president William Turner confirmed the amateur status of all players who had signed with the AAPF and the ALPF had been reinstated.[105] That Turner and the AFA focused on players’ amateur status is also curious. As local reports make clear, players on New England League teams who had not signed with ALPF clubs also considered themselves professionals and were identified as such.[106] Other reports make clear that players who were owed “back salaries” by local clubs were paid before the start of the 1894-95 season, with local businessmen chipping in by subscription.[107] It is clear the AFA didn’t have a problem with professional players so much it had a problem with AAPF and ALPF pros. The association didn’t like competition from the new leagues and so they punished the players that joined them. With both leagues now gone the AFA no longer needed to continue its ban. So, all five New England league clubs, along with the Taftville team from Connecticut, were in the six-team Eastern Division of the 1895-96 edition of the American Cup along with six teams from New Jersey and New York in the Western Division.

On November 2, the Olympics opened up the tournament with an easy 7-2 victory over Taftville. Reports in Fall River newspapers emphasized the Connecticut team was made up “of men who formerly played in England and Scotland.” Five of the Olympics had played for Brooklyn or Boston.[108] The other four New England League teams met in first-round matches on November 9. In Pawtucket, 700 were on hand to see the Free Wanderers and Y.M.C.A. teams play to a 1-1 draw in a game that included no ALPF professionals.[109] In the replay at the Dexter Street Grounds on November 28, Thanksgiving Day, the Free Wanderers were 5-3 victors in front of some 1,500 spectators.[110] Seven former ALPF professionals were scattered between the teams when Rovers defeated East End 4-1 on November 9 but a protest from the losing side was upheld to force a replay.[111] When the teams met again on Thanksgiving Day afternoon, East End surprised by fighting to a 5-5 draw after Rovers had lost a New England League match to Olympics in the morning.[112] Poor pitch conditions resulted in the postponement of the replay scheduled for December 9.[113] On Christmas Day, six former ALPF professionals were with Olympics when the team traveled to Pawtucket to face the Free Wanderers in front of 600-800 spectators and returned home with a 7-2 victory.[114] No former ALPF players were with Free Wanderers despite an earlier report that three would be joining the team for the cup-tie.[115] When the Rovers-East End replay was finally played off on January 4, 1896, seven former ALPF professionals were on the teams’ rosters. The bitterly cold conditions kept attendance down and the game was played in 30-minute halves. This time the Rovers scored five unanswered goals to advance to the semifinals where they would face Olympics.[116]

Conditions “were perfect for football” for a change when the teams met on February 22 at the Olympics home grounds in front of “nearly 500, the largest paid attendance of the season.”[117] On the Olympics roster for the semifinal cup-tie were six former ALPF players, three from the Boston team and three from Brooklyn. The Rovers lineup included four former Brooklyn players. A tight and exciting contest followed that ended in a 2-1 win for the Olympics. One local report described, “The contest reminded one of an old-time battle, such as was played when the game was in its prime, three years ago.”[118]

The constant lament in newspaper reports for the better days of only a few years past when thousands would regularly be on hand for matches in Fall River and Pawtucket reflected the precarious state of soccer in the area. A report in January commented on “the almost total collapse of interest in the game of association football” in the New England League’s jurisdiction.[119] The Rovers and East Ends were notorious for not showing up for scheduled games or showing up understrength. The loss of so many players to the ALPF had grievously affected the level of play the previous season, and that combined with a season of bad weather were blows from which the league continued to struggle to recover despite the return of some of the ALPF players.

While some viewed the declining attendance at games as the result of the pernicious effects of professionalism, Fall River was, like the country at large, experiencing the ongoing effects of the Panic of 1893 and the economic depression that followed.[120] In reaction to decreased demand, in August 1894 before the AAPF and ALPF took the field, Fall River’s manufacturer’s association ordered “all mills controlled by the association to close their doors” for a month, throwing 23,000 operatives out of work.[121] By the middle of September, some 38,000 workers were on strike and did not return to work until the end of October.[122] Decreased demand was not the only factor in Fall River-area mill owners leaning on workers to reduce costs. Textile manufacturers in northern cities like Fall River faced competition from mills in southern states where workers worked longer hours and earned smaller wages, making “the cost of labor in the South about 40 per cent. less than in the North.”[123] By December 1897, the Fall River manufacturers association unanimously voted to further reduce the wages of workers by 10 percent.[124] Wages before the reduction for the 28,000 workers in the 75 local mills affected were between $1.50 and $12 a week, about $45 to $360 in today’s value.[125] With reduced demand and competition from the availability of cheaper products, mills continued to be shut down by owners to reduce production and drive up prices, leaving workers with the equally painful decision between accepting enforced work stoppages and reduced wages or going on strike. Allocating 25 cents to stand on muddy ground in wind and rain to see a soccer game in which teams may or may not show up with their full side, or show up at all, then becomes a luxury many could ill afford. The economic uncertainty that hung over much of the country following the Panic of 1893, particularly in the industrial towns and cities of the Mid-Atlantic states and New England, took a toll on the stability and growth of soccer through the rest of the 1890s.

At the end of March, following in the footsteps of the Mayor’s Cup, the New England League announced it was ending the season early due to the poor financial state of the league and its clubs. The Rovers had stopped appearing for matches and seemed “to be a thing of the past,” East End had disbanded, and interest in Pawtucket was lacking. What little money was left in the league’s treasury was used to purchase medals for the Olympic players, who were undefeated in all competitions.[126] So poor were the Olympics’ finances that a subscription was taken up to pay for their expense to the American Cup final, which was held on April 18, 1896, at Cosmopolitan Park in East Newark in New Jersey against the Paterson True Blues.[127]

Nevertheless, when the team departed on April 17 by boat to New York to begin their journey, they were favorites to win in their hometown press. Instead, the Olympics side, with six former ALPF players, was crushed 7-2 by the True Blues. It was their first loss of the season.[128] Said the Fall River Daily Herald, “In a word, they were beaten to a standstill.”[129] Eight of the True Blues had been on the Paterson AAPF team including former Olympics forward Robert Spencer, who scored twice against his old club. Former Boston forward John Sunderland scored both of the Olympics’ goals. The next day, the Olympics played Newark Scottish Americans in an exhibition game and lost 5-0. On April 21 the team arrived home in Fall River, “in good condition, having enjoyed the trip.” They had “no excuse to offer for their defeat; they met a faster team and therefore the result was natural.”[130]

Frozen Out

A few days after the American Cup final, a review of the state of soccer in the Fall River area reported the “general opinion among the few who have patronized association football this season is that next year no team will be organized, and that the game will be a thing of the past in this city, where three years ago it was the reigning sport.” If the Olympics had won the American Cup it would’ve been necessary to organize a team to defend the title, “but as they lost, it is probable that no team will be formed.”[131] In October it was announced the New England League would not organize games. The Rovers’ grounds had been sold and the East End grounds were not in playable condition because they had not been maintained over the summer. With fans losing interest, and clubs losing money, it was “useless” to continue.[132] The Olympics tried to continue, winning an exhibition game on October 10 against local side Floats, the same day it was reported the New England League would not organize.[133]

With the absence of a local league, local promoters wanted the Olympics and the Rovers to play a series of games aimed at determining a select “Fall Rivers” side to enter the 1896-97 American Cup “for the purpose of getting and keeping the cup until the interest in the game was once more aroused.”[134] But when inquiries were made with the AFA it was learned the association had already organized the tournament and completed the draw for the first round. Fall River’s application was too late: “The Olympics and clubs in the East had been frozen out.”[135] Instead, the American Cup roster of teams was down nine clubs, with three from Newark, two from Paterson, and one each from Kearney, New York, Philadelphia, and Taftville.[136]

With that news the Olympics were done and its players moved on to other clubs such as the Volunteers.[137] Exhibition games played for a prize purse such as the series between Acorns and Floats featured a sprinkling of former ALPF players and drew large crowds, including some 2,000 people on Thanksgiving Day.[138] But organized league soccer in Fall River and vicinity was for now done.

For more on the AAPF and the ALPF, see Philadelphia and the other first professional soccer league in the U.S. (2015) and The AAPF and the ALPF: The beginnings of professional league soccer in the United States (2018).

Notes

[1] See Ed Farnsworth, “The AAPF and the ALPF: The beginnings of professional league soccer in the United States,” Society for American Soccer History, July 24, 2018, accessed March 7, 2020 https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/the-aapf-and-the-alpf-the-beginnings-of-professional-league-soccer-in-the-united-states/

[2] “The Football League Disbands,” Washington Post, Oct. 21, 1894, 6.

[3] “Imported Professional Players,” Public Ledger, Oct. 20, 1894, 19.

[4] Another Pennant: Baltimore to Fly the Emblem of Foot-Ball Championship,” Baltimore Sun, Oct. 22, 1894, 7.

[5] “Another Pennant,” 7. The league table published on page 6 of the Oct. 19, 1894, edition of the Baltimore Sun also has a column for win percentage.

[6] “Another Pennant,” 7.

[7] “Professional Football,” Sporting Life, Mar. 3, 1894, 7.

[8] “Professional Football,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 20, 1894, 3.

[9] “A Professional Football League,” The Times (Philadelphia), Aug. 15, 1894, 6.

[10] “Baltimore’s Foot-ball Team,” Baltimore Sun, Oct. 9, 1894, 6; “Another Pennant,” 7.

[11] “Sporting News and Comment,” Washington Post, Oct. 17, 1894, 6.

[12] “Football Games,” Paterson Morning Call, Oct. 15, 1894, 8.

[13] “Will Reorganize in the Spring,” The Times (Philadelphia), Oct. 21, 1894, 9.

[14] “Foot-Ball Victors: Philadelphia Defeated by Six Goals to One,” Baltimore Sun, Oct. 24, 1894, 6.

[15] “Field of Sport: Baltimore’s Champion Foot-Ball Club wins Again,” Baltimore Sun, Oct. 26, 1894, 6.

[16] “The Professional Game,” Baltimore Sun, Oct. 29, 1894, 7.

[17] “Byrne’s Foot Ball Team,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 7, 1894, 8.

[18] “Player Details: Fagan, Barney,” retrieved March 24, 2020 http://www.fitbastats.com/hibs/player.php?playerid=5492; “Rovers Champions,” Fall River Globe, Apr. 15, 1889, 4.

[19] “Brooklyns to Remain Together,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 22, 1894, 1.

[20] “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Oct. 19, 1894, 4.

[21] “Brooklyns to Remain Together,” 1.

[22] “Football Passes,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Oct. 24, 1894, 4; “Brooklyns to Remain Together,” 1.

[23] “Footballists Convene,” Newark Sunday Call, Sep. 16, 1894, 6; “Association Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 27, 1894, 6; “From the Football Field,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 9, 1894, 7.

[24] “Football at Night,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 13, 1894, 7.

[25] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 24, 1894, 8.

[26] “Brooklyns vs. Baltimore,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 29, 1894, 1.

[27] “Baltimores vs. Brooklyns,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 30, 1894, 8; “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Oct. 31, 1894, 5.

[28] “Baltimore Team’s Trip,” Baltimore Sun, Oct. 30, 1894, 6.

[29] “Championship of America,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 31, 1894, 7.

[30] “Baltimore Team’s Trip,” 6.

[31] “Captain Shea’s Letter,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 20, 1894, 1.

[32] “Baltimore Team’s Trip,” The Baltimore Sun, Oct. 30, 1894, 6.

[33] “Great Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 2, 1894, 7.

[34] ‘Of Football Between Baltimores and Brooklyns,” Fall River Daily Globe, November 2, 1894, 1.

[35] “Great Football,” 7.

[36] “Two Goals To Two,” Baltimore Sun, Nov. 2, 1894, 6

[37] “Great Football,” 7.

[38] “Of Football,” 1.

[39] “Two Goals To Two,” 6.

[40] “Great Football,” 7.

[41] “Easy for Brooklyn,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 5, 1894, 6; “Brooklyn Defeats Baltimore,” Baltimore Sun, Nov. 5, 1894, 9.

[42] “Easy for Brooklyn,” 6.

[43] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 5, 1894, 7.

[44] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 8, 1894, 7.

[45] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 3, 1894, 1

[46] “The Baltimore Professionals,” Baltimore Sun, Nov. 10, 1894, 6.

[47] “Dull Game,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 12, 1894, 1.

[48] Dull Game,” 1.

[49] “Dull Game,” 1, “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 12, 1894, 1.

[50] “Sporting,” Baltimore Sun, Nov. 13, 1894.

[51] “Great Football,” 7.

[52] “Easy for Brooklyn,” 6.

[53] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 12, 1894 8.

[54] “Football Gossip,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 17, 1894, 8.

[55] “Variety of Sporting,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 16, 1894, 7.

[56] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 24, 1894, 7.

[57] “The Professional Kickers Disband,” Baltimore Sun, Nov. 21, 1894, 6.

[58] “Football Passes,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 30, 1894, 4.

[59] “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Dec. 24, 1894, 8.

[60] “Boston Begins Well,” Boston Daily Globe, Oct. 7, 1894, 16.

[61] “Out for the Cup,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 31, 1896, 7.

[62] “Sporting Miscellany,” Boston Daily Globe, Nov. 25, 1894, 5;

[63] “Boston Football Team Complains,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 7, 1894, 8.

[64] “Boston Football Player Brings Suit,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 9, 1894, 6.

[65] “Sporting Variety,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 12, 1894, 7.

[66] “Suit Has Been Entered,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 8, 1895, 8; “City Briefs,” Fall River Herald, Mar. 30, 1895, 6.

[67] “Football Players Get Their Money,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Dec. 18, 1895, 5.

[68] “Small Crowds,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 26, 1894, 1; “Christmas Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 26, 1894, 6.

[69] “Christmas Football,” 6. It appears four players who were not part of ALPF league games featured on the Boston side.

[70] “Small Crowds,” 1.

[71] “Small Crowds,” 1. The Fall River Daily Herald’s has a different sequence of goals and reports Brooklyn scored after a minute of play with Boston equalizing “shortly afterwards,” after which Brooklyn scored again with Boston equalizing just before the half. Brooklyn next took the lead again in the second half to make it 3-2 before Boston equalized again. Brooklyn then scored the game-winning goal just before the final whistle. “Christmas Football,” 6.

[72] “No Professional Foot Ball,” New York Press, Dec. 20, 1894, 4.

[73] “The Mayor’s Cup,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 28, 1894, 7.

[74] “Brooklyns Win,” Fall River Daily Globe, Jan. 14, 1895, 1.

[75] “Football Passes,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Feb. 4, 1895, 4.

[76] “East Ends Lose,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 11, 1895, 7.

[77] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Mar. 6, 1895, 7.

[78] “Mayor’s Cup Series,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 8, 1895, 7.

[79] “Football Resumed,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 25, 1895, 7.

[80] “Two Games,” Fall River Daily Globe, Mar. 25, 1895, 1.

[81] “Football a Dead Duck,” Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 1, 1895, 1; “Another Flunk, “ Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 8, 1895, 1; “Gossip of the Football Field,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 10, 1895, 7.

[82] “Three To One,” Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 8, 1895, 1.

[83] “Football Gossip,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 3, 1895, 7.

[84] “No Games Saturday,” Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 15, 1895, 1.

[85] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, April 18, 1895, 8.

[86] “Variety of Sporting,” Fall River Daily Herald, April 26, 1895, 7; “Football Gossip,” Fall River Daily Herald, May 22, 1895, 7.

[87] “Football Gossip,” 7; “Olympics Get the Money,” Fall River Daily Herald, June 3, 1895, 6.

[88] “Cup Goes West,” Fall River Daily Herald, June 3, 1895, 7.

[89] “Hot Kicking,” Fall River Daily Globe, June 3, 1895, 1.

[90] “Caledonians Won the American Cup,” Fall River Daily Evening News, June 3, 1895, 8.

[91] “To Revive the Sport,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 6, 1895, 1.

[92] “Players Assigned,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 6, 1895, 1.

[93] “East Ends Admitted,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 30, 1895, 1; see the East End roster in “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Oct. 18, 1895, 7.

[94] “Officers Elected,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 16, 1895, 7.

[95] “American Association,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 23, 1894, 1; “Association Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 2, 1895, 6.

[96] “Association Football,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 17, 1894, 6.

[97] “Some Dissatisfaction,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 17, 1894, 1.

[98] “Football Prospects,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 19, 1894, 8.

[99] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, Aug. 11, 1894, 7.

[100] “Signing Players,” Fall River Daily Globe, Aug. 25, 1894, 7.

[101] “A Variety of Sporting,” Fall River Daily Herald, Aug. 28, 1894, 7; “Professionals Win,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Sep. 4, 1894, 4; “Brooklyn’s Win,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 4, 1894, 6.

[102] “Contracts Signed,” Fall River Daily Globe, Aug. 30, 1894, 8.

[103] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 11, 1894, 7; “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Sep. 13, 1894, 1.

[104] “New England Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 24, 1894, 7.

[105] “Association Football,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Dec. 17, 1895, 5.

[106] See for example, “Out for the Cup,” 7.

[107] “Football Probabilities,” Fall River Daily Globe, Aug. 17, 1894, 1.

[108] “For American Cup,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 4, 1895, 7; “Association Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 4, 1895, 1.

[109] “Cup-Tie Ended In A Draw,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 11, 1895, 1.

[110] “Free Wanderers 5, Y.M.C.A 3,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 29, 1895, 6.

[111] “Two Cup-Ties,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 11,1895, 1; “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 22, 1895, 7.

[112] “Rovers 5, East Ends 5,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 29, 1895, 6; “Olympics 6, Rovers 0,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 29, 1895, 6; “Resulted In a Tie,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 29, 1895, 1; “Rovers Meet Defeat,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 29, 1895, 1; “Association Football,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 29, 1895, 1.

[113] “Football Game Postponed,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 9, 1895, 1.

[114] “For American Cup,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 26, 1895, 1; “Rovers and Olympics Win in Pawtucket,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Dec. 26, 1895, 5.

[115] “Association Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 6, 1895, 7.

[116] “Rovers Won,” Fall River Daily Globe, Jan 6, 1896, 1; “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Jan. 6, 1896, 5.

[117] “Olympics Win Cup-Tie,” Fall River Daily Globe, Feb. 24, 1896, 1.

[118] “Olympics Win,” Fall River Daily Herald, Feb. 24, 1896, 7; “Foot Ball,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Feb 24, 1896, 5.

[119] “Football Passes,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Jan. 6, 1896, 5.

[120] On the effects of professionalism, see for example “American Game Postponed,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 12, 1894, 7.

[121] “Gates to be Barred,” Fall River Daily Globe, August 23, 1894, 1

[122] “Getting Hot,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 14, 1894, 1; “Vote to Strike,” Fall River Daily Globe, Sep. 15, 1894, 8. Appletons’ Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1894. (New York: D. Appleton, 1895). 264; “Wheels Whizzing,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 30, 1894, 1.

[123] Appletons’ Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events of the Year 1894. (New York: D. Appleton, 1895). 502.

[124] “Another Blow for Fall River,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 9, 1897, 1.

[125] “General Gloom,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 10, 1897, 1.

[126] “Association Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Herald, Feb. 17, 1896, 1; “Out for the Cup,” 7; “American Cup-Tie Game,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Apr. 13, 1896.

[127] “Olympic Men’s Friends,” Fall River Daily Globe, Mar. 25, 1896, 7; “Subscription List,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Mar. 25, 1896, 5.

[128] “What a Surprise!” Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 21, 1896, 1; “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Apr. 21, 1896, 5. The Globe and Daily Herald reported attendance for the final at between 6,000 and 7,000. The Daily Herald reported attendance “at over 2,500. “Saved the Cup,” River Daily Herald, Apr. 21, 1896, 7.

[129] “Saved the Cup,” 7.

[130] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, Apr. 21, 1896, 8.

[131] “Football Gets a Rest,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 25, 1895, 7.

[132] “No Football Games,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 10, 1896, 6.

[133] “Local Lines,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 12, 1896, 8.

[134] “Frozen Out,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 27, 1896, 8.

[135] “A Freeze-Out,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 27, 1896. 7.

[136] “Association Football,” The Amateur Athlete, Oct. 15, 1896, 4.

[137] “In and About the City,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 4, 1896, 8.

[138] “Football Contest,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 5, 1896, 8; “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 12, 1896, 12; “Neither Scored,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 15, 1896, 6; “A Tie Game,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 16, 1896, 6; “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Nov. 27, 1896, 5.

Pingback: The AAPF and the ALPF: The beginnings of professional league soccer in the United States – Society for American Soccer History

ozghix

Pingback: Kicking off those Bunglesome Bloomers: Women’s Soccer in Baltimore, 1920-23 – Society for American Soccer History