On March 14, 1921, Levi Wilcox reported at the Philadelphia Inquirer the impending arrival of Scottish first division side Third Lanark for a North American tour. While the bulk of the tour would be played in Canada– the tour was financed by the Dominion Football Association of Canada, Canada’s FA — the team would also play in the United States. Wilcox wrote “at least one match will be played in this city, probably against a picked team composed of the leading players which will include a number of Bethlehem stars.”

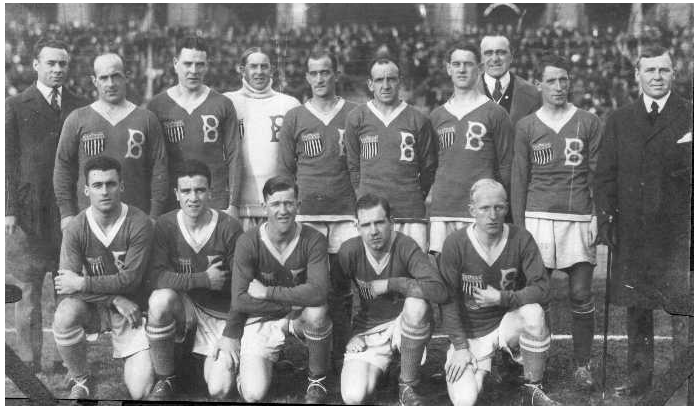

Wilcox noted the Third Lanark side would “include a number of players from other teams…owing to some of the regulars not being in a position to spare time to make the trip.” The team was thus more correctly referred to as the “All-Scots,” despite it being referred to as Third Lanark in most U.S. newspaper reports. However, while the tour had the approval of the Scottish FA, the team was not endorsed by the SFA as a national team side.

In the event, while four Third Lanark players would be with the team, eleven players came from seven other Scottish clubs, six from the Scottish first division (Partick Thistle, Motherwell, Dumbarton, Aberdeen, Ayr United, and Albion Rovers) and one from the Central Football League (Dunfermline Athletic), which because of its independent status could offer players higher wages than the maximum allowed to teams in Scottish League play. Conspicuously absent were any players from Rangers, Celtic, Heart of Midlothian, or Dundee, the top four teams in the first division after the 1920-1921 season. Prior to the tour, five of the players had appeared for Scotland in international play, and one player would do so after the tour.

With the First World War ravaging Europe through the heart of the 1910s, no international side had visited the U.S. since the 1911 Corinthians tour. More importantly from a competitive standpoint, the All-Scots tour would be the first ever in the U.S. by a team made up of professional players. Equally important from an organizational standpoint, it would be the first-ever domestic tour by an international team to take place under the auspices United States Football Association (USFA), known today as the United States Soccer Federation, which had approved the tour at its annual meeting on May 25, 1921, held that year at the Hotel Walton in Philadelphia, located on the southeast corner of Broad Street and Locust Street. Thomas Cahill was given the responsibility of making arrangements for the U.S. portion of the tour.

Wilcox expected the team would be “the strongest aggregation ever sent here.” He wasn’t wrong.

Leaving Liverpool for Canada aboard the Cunard liner Cameronia on May 11, 1921, the Scots began the first part of their tour with a 7-0 win over Halifax on May 25. A month and a half later, having sometimes played in the red colors of Third Lanark, other times in a white jersey bearing a thistle that evoked the kit worn by previous Scotland national team sides, they finished the Canadian portion of the tour with a 1-0 win over a Canada XI team in Montreal on July 9. Undefeated through 19 games, they had outscored their opponents 87 goals to 9, with 11 shutout victories.

In New Jersey a day later on July 10, the Scots faced Jersey City Celtics, described by Spalding’s Official Soccer Football Guide for 1921-1922 as a team “composed of players recruited from clubs around New York,” in their first game in the U.S. Despite a “splendid exhibition” from Celtics — and two hours of heavy rain immediately before the start of play — the Scots defeated the home side, 4-2. It was only the second time in the tour the visitors gave up more than one goal.

Next up were Bethlehem Steel followed by the All-Philadelphia team.

Internationals in Philadelphia before 1921

The Philadelphia area had hosted its first international friendly on October 8, 1901 when a “Gentlemen of Philadelphia” team made up of players from the city’s cricket clubs faced “Bosanquet’s XI,” an English cricket team then touring the U.S., at West Philadelphia’s Belmont Cricket Club in a game of soccer. While the local team lost, 6-0, the game was widely covered in the local press and helped to boost interest in soccer, which was still recovering from a downturn following the economic crisis of the mid 1890s, increasing support of soccer among the city’s class of Anglophile elites. Teams were formed throughout the area, including one backed by Connie Mack of baseball’s Philadelphia Athletics, to join the city’s now growing roster of leagues.

That positive momentum was furthered when the touring English amateur side The Pilgrims came to Philadelphia for three games in October of 1905. The local sides again showed their inexperience and the Pilgrims won by a cumulative total of 19 goals to 1, defeating an All-Cricket Club League Best XI 4-1 on October 6 before breezing past an All-Philadelphia team made up of league players 5-0 on October 7, and then trouncing a team made up University of Pennsylvania students and alumni 10-0 on October 24. Crowds had been strong for each game — the Inquirer reported that attendance for the All-Philadelphia match on October 7 “was estimated to be around 15,000 persons” — and interest from area soccer fans in seeing the game played at its highest level was plainly evident. The All-Philadelphia team fared better when, only weeks after the Pilgrims’ visit, the University of Toronto team arrived in Philadelphia for three games, winning the first game 3-0 on November 30. The All-Cricket Club League team was defeated 4-1 by the Canadian visitors on December 1, with the University of Pennsylvania team losing 5-1 the next day.

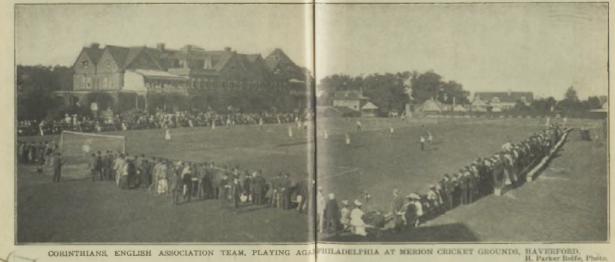

The next year in 1906, England’s famous Corinthians team, another amateur side, toured the U.S., stopping in Philadelphia for three games. They were easy winners in each game, defeating the All-Cricket Club team 6-0 on August 31, 1906, the Albion team 9-0 on September 1, and the All-Philadelphia team 12-0 on September 3.

Both the Pilgrims and Corinthians would return to the U.S. for tours. In 1909, the Pilgrims again played three games in Philadelphia, defeating an Associated Cricket Clubs League team 3-0 on November 2, 1909 before crushing an All-Philadelphia side 9-0 on November 6. Remarkably, Philadelphia’s Hibernian team defeated the visitors 1-0 on November 4, the English side’s first loss of the tour. Corinthians returned in 1911. The American Football Association had prohibited member clubs and players from facing the English team so this time there was only one game in Philadelphia, against an All-Cricket Club side.

Corinthians won, 19-0.

Great anticipation

The U.S. soccer landscape had changed dramatically since the 1911 Corinthians tour. The USFA had been formed in 1913 and soon gained official recognition from FIFA. The inaugural edition of the National Challenge Cup, now known as the U.S. Open Cup, had also been launched in 1913 and was well on the way to replacing the AFA’s American Cup tournament as the country’s premier — and truly national — soccer tournament. After Bethlehem Steel had passed on the offer, the USFA had sent its first official national team side on a Scandinavian tour in 1916, finishing with a respectable 3–1–2 record, 1–0–1 in full internationals. Bethlehem Steel had embarked on a Scandinavian tour of its own in 1919, becoming the first U.S. professional club side to tour outside of the U.S., finishing with a 7–2–5 record, outscoring their opponents 22–14. A St. Louis team followed Bethlehem Steel to Scandinavia in 1920, also returning home with a 7–2–5 record. By the time of the arrival of the All-Scots, work was underway for the debut of the American Soccer League, the country’s first fully professional Division I league, for the 1921-1922 season.

By 1921, Bethlehem had laid down its claim as being the top team in the country. After joining Philadelphia’s Allied Amateur Football Association in 1912 — winning the league championship in its first year, adding another league championship as well as the Allied Amateur Cup and the American Football Associations American Cup in its second year — the team joined Philadelphia’s American League of Association Football Clubs for the 1914-15 season, winning the league championship and it’s first U.S. Open Cup. By 1921, it had added three more U.S. Open Cup titles to its list of achievements, as well as four more American Cup titles, and three straight championships in the semi-professional National Association Football League.

Still, aside from the league championship, the 1920-21 season had been a disappointment, with the team eliminated in the semifinals of the American Cup, and in the second round of the U.S. Open Cup. A report at the Inquirer on July 10 noted some felt 1921 American Cup and U.S. Open Cup champions Robins Dry Dock should’ve been hosting the All-Scots rather than Bethlehem. But, the report noted, “Although Robins Dry Dock accomplished the double feat last season many closely identified with the game are of the opinion that the Bethlehem machine at the end of the season was stronger than Robins, particularly as this same Bethlehem aggregation defeated Robins in the National League series and won the championship of that circuit. It is on account of that that Bethlehem is picked to extend the Scotchmen.”

As for why Philadelphia was selected to face the All-Scots, the Inquirer’s hometown assessment was blunt: “As Philadelphia has long been recognized as the home of soccer, and it was in this city where the first game was played in this country”. (Sadly, no date is provided to back up the claim that the first game of soccer played in the US took place in Philadelphia.)

Nevertheless, the match against the All-Scots on July 13, 1921 was an opportunity for Bethlehem to test itself against a team made up of players from perhaps the second best professional league in the world after England’s top flight, even if the game would pit a Scottish team in top form after playing 20 games together on tour against a Bethlehem team in the middle of its offseason. The Bethlehem Globe reported on June 24, “It is well known that the visitors are anxious to add the Bethlehem clan to their big list of victories because the local team is regarded as the last word in American football. However, the visitors will probably have a harder time of it than they expect as every man on the Bethlehem list has been looking forward to the game with great interest, and they are training hard and will be in good condition when the referee sets the game in motion.”

While Bethlehem’s citizens historically had not supported the city’s famous soccer team in great numbers, despite the team’s great success, expectations for this match were different. The game, which The Globe reported on June 16 would see the All-Scots receiving a guarantee “said to exceed the thousand-dollar mark” (about $13,500 in today’s value), would be the first-ever international to be played in Bethlehem, and The Globe reported on June 30 the launch of a public relations campaign to drum up interest, one which would “take in not only the larger cities of this section, but every town and village within a radius of thirty miles.” The report continued,

A thorough canvass of the shops of local industrial plants and business houses in the Lehigh Valley will also be made in the near future. Secretary A. H. Buck of the Bethlehem Chamber of Commerce will also lead the cooperation of that body, by requesting all business men to close their establishments an hour earlier than usual in order to allow employees to witness the game which will start at 5:30 p.m.

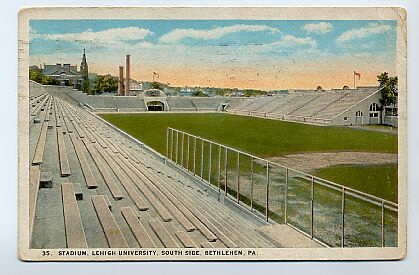

Indeed, expectations for a big crowd were such that the game, which would be played on a Wednesday, would take place at Lehigh University’s Taylor Stadium rather than the team’s own Steel Field.

So seriously were the preparations being made for the game that a party of thirteen Bethlehem Steel players traveled to see the All-Scots take on Jersey City Celtics in their first game of the U.S. portion of the tour. Displaying perhaps an over-exuberant hometown pride, The Globe reported on July 8, “The management of the tourists will no doubt expect the presence of the Bethlehem players and it is quite probable that many of the stars will be held in reserve for the game in Bethlehem and substitutes played against Jersey City.”

“Wow, but what a drubbing…”

The All-Scots did make six changes when they lined up against Bethlehem Steel on July 13 and for the first 45 minutes of the game, the home team’s scouting of their international opponents seemed to pay off. In the opening minute of the game Bethlehem outside left Tommy Fleming delivered a hard shot. Third Lanark and Scottish international goalkeeper Jimmy Brownlie, described by the Globe as “the best custodian in Europe,” slipped and fell as he moved to cover the shot, which struck the crossbar before going out of play.

It would be Fleming who opened the scoring with what the Globe reported was a “low drive into the corner of the net,” and the 3,000 fans on hand for the game “went wild with enthusiasm” after the hometown goal. Four minutes later, Aberdeen outside right Doug Thompson equalized for the visitors when his shot “was poorly handled” by Bethlehem goalkeeper Duncan. Play continued evenly after that and the scoreline stood at 1-1 at the end of the half.

In the second half, the All-Scots proceeded to run over Bethlehem. Eight minutes after the start of the second half, Partick Thistle and Scotland inside right Jim McMenemy gave the visitors the 2-1 lead. A few minutes later, a headed goal from Dunfermline Athletic and Scotland center forward Andy Wilson made it 3-1.

The Globe reported, “The Scotchmen seemed to have complete control of the situation and they gave a demonstration of football superior to anything ever seen in this country. The ball was passed from player to player with such precision and accuracy that the spectators simply marveled at the exhibition.” Soon Thompson scored again for the visitors, followed by another goal from Wilson. Dunfermline Athletic inside left Tom Maxwell added another goal to make it 6-1 before Wilson and Thompson each added another goal to complete individual hat tricks. At the final whistle it was Bethlehem Steel 1-8 All-Scots. The Globe described, “Spectators who witnessed the play in the first half could not understand the catastrophe which took place in the last thirty minutes. The team hardly appeared to be the same that started against the Scotchmen.” It was Bethlehem’s worst defeat since the fall of 1907 when the team was downed 11-2 and 9-0 by West Hudson in the span of a few weeks.

Reports at both the Globe and the Philadelphia Inquirer laid much of the blame on the “apparent inability” of Bethlehem goalkeeper Duncan “to gauge the flight of the ball.” The Globe said Duncan should have saved “at least four” of the goals, while the Inquirer’s Levi Wilcox said he should have stopped “at least three.” The Inquirer also underscored the disappointing play of Bethlehem’s halfbacks, including former Brighton and Hove left halfback Rutherford, as well as former Chelsea center forward Harold Brittan. Conditioning was also certainly a factor: Bethlehem was in the middle of their offseason. The Globe also reported a team official said Bethlehem was disadvantaged by “the short sized cleats worn on the shoes of the home team in playing on the heavily sodded turf, while those worn by the Scotchmen were easily again as long.”

Excuses aside, it was a dispiriting defeat. Wrote the Globe, “After all, in viewing the game from every available angle, it was simply the case of the better team winning.”

After the game, a banquet was held in honor of the visiting Scotsmen in which several visiting players and team officials remarked upon “the well-organized cheering of the ‘Sand Lot Brigade’ herded together in one section of the stands.” The Globe reported on July 14 that All-Scots goalkeeper Brownlie remarked “this continual howling by the kids was working on his nerves and apparently was something new in his experience.” Said J.H. Connell, theGlasgow Evening Times sports editor who was acting as the team’s tour manager, “If you can teach the boys to play football as well as those youngsters can yell, the sport will be a success.”

All-Philadelphia takes on the All-Scots

The All-Scots arrived in Philadelphia on Friday, July 15, the day before their match against the All-Philadelphia team at Disston Ball Park, located at State Road and Unruh Street in the city’s Tacony section. After a sightseeing tour of the city, the team had a short practice at Disston Park. The day of the game they were treated to an early banquet at the Manufacturer’s Club.

Kickoff on July 16 was scheduled for 6 pm, Levi Wilcox describing in the Philadelphia Inquirer’s match preview published the day of the game, “That time having been arranged so that it will give those interested in baseball a chance in which to witness their favorite pastime and then attend the soccer match.” The scheduling was both a smart and realistic move, as evidenced by the opening sentence of the match preview in the Philadelphia Public Ledger on July 16, which began, “Soccer enthusiasts in this city, and they number thousands, will get their long-looked-for opportunity this afternoon…” While Philadelphia was without question one of the premier soccer centers in the U.S., plenty of readers needed to be reminded of soccer’s strong local following. The scheduling consideration seemed to payoff for Wilcox described in the Inquirer’s July 17 match report that “the biggest crowd that has attended a game in this city since the visit of the English Pilgrims” turned out to see the All-Scots.

Ahead of Bethlehem’s embarrassing defeat to the All-Scots, the Inquirer reported on July 4 “it is almost a certainty that the Philadelphia team will include more than one Bethlehem star,” later reporting on July 10 the expectation that a “majority” of the players would come from Bethlehem Steel. This was perhaps a reflection of the fact the roster of the Philadelphia FC team that would be playing that fall in the inaugural season of the new professional American Soccer League would largely be filled with Bethlehem players. But it was also based on the desire to field as competitive a team as possible. While acknowledging “a strong team could be selected from players in this city,” the Inquirer emphasized on July 4 the experience provided by Bethlehem players would make the matchup “more evenly balanced.” The report concluded, By including Bethlehem players it will not in the least lower the prestige of this city as a soccer centre owing to the fact that the Bethlehem team is affiliated with the Football Association of Eastern Pennsylvania and District, which has its headquarters in this city.”

In the event, five Philadelphia-based players were added to the All-Philadelphia starting XI: Disston goalkeeper Johnny Ness, right fullback Bobby Bethune, Disston winger Percy Andrews, and Bart and Jim McGhee brothers, two brothers who played as forwards for Wolfenden-Shore in the city’s Industrial League. The visitors made one change to their lineup, starting Motherwell’s Willie Rankin at inside right over McMenemy.

As had been the case in Bethlehem, the home team was the first to score, this time 20 minutes after the opening whistle, thanks to outside right Percy Andrews. After making “a clever dribble on the right wing where he outwitted the Scots’ backs,” Andrews saw his shot saved. However, Wilcox described, “The Scots’ custodian did not grip the ball properly which rebounded off his chest and quick as a flash Andrews, who had followed up his shot, banged the ball into the net.”

The lead was short-lived.

Right from the re-start, Wilcox reported, the All-Scots “started bombarding the Phillies’ citadel.” Center halfback Rutherford “in attempting to ‘trap’ the sphere, had the misfortune to foul” Motherwell inside right Willie Rankin. Scottish international center forward Andy Wilson made no mistake from the penalty spot to make it 1-1 four minutes after All-Philadelphia’s goal.

The experience of facing the All-Scots three days before was evident in the improved showing of the defense and midfield, which, Wilcox reported, “In marked contrast to the game on Wednesday…held the fleet-footed Scotchmen.” But, in his July 15 match preview for the Inquirer, Wilcox, who had seen the All-Scots play both Jersey City Celtic and Bethlehem Steel, observed, “we are of the opinion that as the game progresses that they seem to get stronger.” The observation held true against All-Philadelphia. Before the end of the half, the visitors made it 2-1. Wilcox described,

The Scotchmen’s second tally resulted after one of the finest exhibitions of dribbling seen since the invasion of the English Corinthians and Pilgrims. The Scotch front liners were fed by Brown around the half-way mark and by a series of passing, repassing, and smart dribbling on the part of Wilson and Company, Rankin banged the ball into the net from a corking shot about twenty yards out which was labeled all the way, from which it may be gathered that Ness did not have the least chance in which to connect with the shot.

Thirty minutes into the second half, Wilson scored the final goal of the game to make it 3-1 after heading in a cross from Aberdeen outside right Doug Thomson. Wilcox reported, “This goal was easily the most sensational of the game, as Wilson was practically ‘hemmed in,’ but his head judgement proved just as good as his feet in controlling the ball for distance.”

It was the All-Scots’ 22nd consecutive win.

The Globe’s match report on July 18 praised the All-Philadelphia team for “the manner in which they thwarted the efforts of the touring clan and if anything not only played equally with the players in the corresponding opposing positions, but at times were superior.” Once again, the Globe laid blame for the loss at the feet of the home side’s goalkeeper “for each of the three shots registered by the Scots were of the savable variety.” The recap of the game in Spalding’s Official Soccer Football Guide for 1921-1922 reported, “The Quakers really put up a great game, but the experience and finish of the tourists fully entitled them to a victory.”

The analysis of the game by Wilcox at the Inquirer provided more nuance.

Although defeated, the Philadelphia team was not humiliated. They played a whale of a game, to use the words of one of their most ardent admirers, while at some stages of the game they even outplayed their more experienced rivals.

However, Wilcox minced no words when he wrote, “The Scotchmen outplayed the Phillies in every department of the game.” To Wilcox, it was clear the visitors were simply of a different class than their American-based opposition. He described in his July 16 match preview,

One of the most outstanding features in connection with the Scots game noticeable more than ever [in their win over Bethlehem] is the formation of the team for various plays. It is not necessary for the captain to coach his players on the field for the purpose of ‘tipping’ them off for the next play as they all seem to have that instinct what to expect, or where the pass is going every time that one of the Scotchmen has the ball at his feet.

In his match report, Wilcox also pointed to the different styles of play:

In both periods, play was of a fast order. The short passing game, compared to the long slinging passing game of the Phillies, giving the spectator the two style of game, with the Scotchmen showing the most finish, particularly in the forwards, where their passing, repassing, and dribbling left nothing to be desired.

For Wilcox, the home team’s shortcomings were not to be found in goalkeeping, but in a lack of teamwork in the attack. “The All-Philadelphia front liners,” Wilcox wrote, were guilty of “being too over-anxious when passing the ball. Time and again they failed to use the least bit of head-work when attempting to pass to one of their confreres, the pass generally being too short.”

Unlike the All-Scots, who were nearing the end of a long tour together, the All-Philadelphia players were in the middle of their offseason, not to mention a team that, irrespective of the Bethlehem Steel core of players, featured an aggregation of attacking players who had never played together before their game at Disston Park. To his credit, Wilcox did not mention this obvious fact. What was more important was conveying the understanding that the All-Scots represented a level of quality not present in the American game.

While the All-Scots games no doubt helped to promote soccer, the games were likely not profitable for local promoters, in part because efforts were made to keep the cost of admission to the games low. The Globe reported on July 23,

Through the efforts of the management of the Bethlehem F. C., local and Philadelphia fans were enabled to witness the game far cheaper than in any of the other four cities where the Scots appeared. The prices in Philadelphia and Bethlehem — 50 cents for general admission and $1 for reservations — were lower than those in New York, Jersey City, Lynn, Mass., and Fall River, where the scale was $1 for general admission, $1.50 and $2 for reservations. The receipts for the local game, it is understood, totaled in the neighborhood of $2,000 while those in Philadelphia were a trifle over $3,000. Deducting the 75 percent privilege, together with the expense of advertising, transportation and the hundred and one other incidentals that cropped up, the local management was fortunate if it broke even in the games played in Bethlehem and Philadelphia.

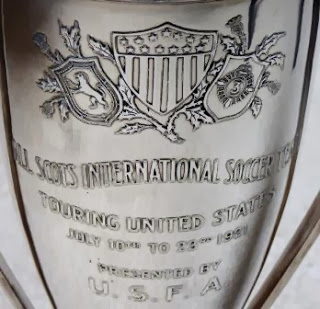

The day after playing Philadelphia, the All-Scots defeated a team of New York All-Stars, 2-1, defeating General Electric team in Lynn, Massachusetts, 6-3, the day after that. In the last game of the tour on July 21, 1921, Fall River United drew 2-2 with the Scots, the only time over 25 games the visitors were not victorious. The night before the team sailed home on the steamer Celtic for Scotland on July 24, they were given a farewell dinner hosted by the USFA, known today as the US Soccer Federation, and presented with a large silver cup “in recognition of the team’s splendid play.”

Six of the players who had appeared for the All-Philadelphia team — right fullback Bobby Bethune, left fullback Jock Ferguson, right halfback Billy Murray, left halfback William Porter, inside right Fred Morley, and center forward Harold Brittan — would form the core of the Philadelphia FC team that won the championship of inaugural 1921-1922 season of the American Soccer League. Also on the Philadelphia FC ASL team was outside left Tommy Fleming, and inside left William Forrest, two players who had been on the Bethlehem Steel team defeated by the All-Scots.

A version of this article first appeared at The Philly Soccer Page on January 26, 2016.

According to the rsssf site the tour was authorised by the Scottish FA on 9 February 1921. Interestingly the Montreal Gazette for 10 February 1921 carries an article on page 8 stating that the tour was to be organised by DG MacEwan the secretary of the Scottish Association Players’ Union.This body was never recognised by the SFA but seems to have played a role in the tour (which may explain why the players were drawn from different clubs). Willie McAndrew of Third Lanark was known to be active within the union. The article can be seen on the Google News Archive:

https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=Fr8DH2VBP9sC&dat=19210210&printsec=frontpage&hl=en