If you had not heard of the Major Indoor Soccer League (MISL) or recall it from the 1980s and 1990s, but never attended a game, YouTube is a veritable treasure trove of historical footage. It can be especially amusing to see familiar names and faces broadcasting an unfamiliar sport. One promotional video for the Cincinnati Kids, for example featured American football analyst Bob Trumpy. Although the quality of the recordings – remember tracking on a VHS machine? – and the play is sometimes lacking, they still provide an interesting record of the league and its not-so-dearly departed clubs, including one from Hartford, Connecticut, called the Hellions. The club was founded in 1979 and over just two seasons compiled a sulphureous 19-53 record before being sold and relocated to Memphis in 1981. While the specific details of the Hellions story are unique, their journey is emblematic of the challenges faced by the MISL. The club’s tale also illustrates larger trends in US soccer history including the lack of continuity of clubs as they folded, relocated, or otherwise disappeared and the general absence of media coverage that takes the sport, players, and fans seriously.

Ed Tepper and Earl Foreman founded the MISL in 1977. Foreman, a veteran of World War II, had been involved in various professional basketball and football teams over the years. Like many organizations, including the American League of Professional Football in 1894, arena operators formed a significant percentage of franchise ownership. The competition lasted a total of fourteen seasons and attracted twenty-seven million fans, more than the populations of Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland combined. The MISL featured different rules than conventional soccer, many of them designed to make the sport more television friendly. Teams played four, fifteen-minute periods using a red ball that was easier to track. Large goals made for high scoring contests and the league boasted that most players were native-born (although this was debatable).

Overall costs to launch the MISL totaled around $3.5 million, and the league lost money in the first year. Despite ending up in the red, the MISL hit projected revenue targets leading to some optimism for the future. Nevertheless, there were a few worrying signs. The Cincinnati Kids, part owned by baseball star Pete Rose, played in the MISL’s inaugural game, and folded at the end of the first season. The Kids’ opponent that day was the New York Arrows who went on to capture the first four MISL titles. Regular visitors to the Arrows home pitch at Nassau Coliseum on Long Island must have been spoiled for success as fellow tenants the New York Islanders won four Stanley Cups in a row between 1979-82. Unfortunately, the soccer team proved less popular than the hockey club and the Arrows went bankrupt after their sixth season. Such actions would be endemic in the league as at least one team went under, moved, or suspended operations after nearly every MISL season. The instability made it difficult to build a fanbase or develop rivalries. Despite such challenges, by 1983-84 the MISL was more popular than the North American Soccer League and after the NASL’s demise in 1985, was the only top-level professional soccer league in the US.

The Hellions began when local broadcaster Roger Simm wanted to bring MISL soccer to Hartford. A friend recommended he partner with an accountant named William Chipman. In addition to his accounting business, Chipman was involved in real estate and leased a restaurant that, like Artie Bucco’s joint Vesuvio in the television series The Sopranos, was destroyed by fire in suspicious circumstances. He had no experience with soccer or other sports. Simm, who lost his house when the Hellions went down in flames, must have regretted his decision to partner with the bean counter, as Chipman was eventually convicted of tax fraud and jailed. Such shady economics were not unusual in the league and Denver Avalanche! owner Ron Maierhofer said it was run by men who “understood the nuances of the federal tax code”[1]. The franchise was awarded to Simm, Chipman and two other major investors on April 24, 1979. They had until mid-September to raise the $600,000 required to launch the team. The ownership sold shares but not enough to reach the funding target. By falsifying records and deceiving investors, they obtained enough money to move forward with the team.

The Hellions joined the MISL when indoor soccer was trying to make its case, not only as a major professional sport, but also as an exciting spectacle. Ed Tepper stated the priorities clearly “We’re more interested in providing entertainment than pure sport.”[2] The league tried hard to market itself to women, at the time a generally untapped market of vast potential. Clubs made it a point to attend community events aimed at families; the Kansas City Comets made over five hundred appearances one season. Other forms of outreach were less wholesome and used sex to appeal to both female and male fans. One campaign run by the Pittsburgh Spirit promised fans “Hot legs, hot time, hot action” by “20 guys in shorts who can go all night.”[3] Many teams had cheerleaders, both male and female with names such as the Snow Cats and Roses. Even the Hellions held tryouts for a squad to be known by the wickedly appropriate and “sexy but tasteful” nickname Hells Bells.[4] Whether appealing to soccer moms or young, unmarried women, the campaign seemed to be successful as the MISL became the first major sport to have women number half its audience.

Still, the league fought an uphill battle against the mainstream sporting press. No figure personified the attitudes of sportswriters more than Frank Deford who at the time was on staff at Sports Illustrated, perhaps the most important athletic periodical in the country. He also made curmudgeonly appearances on Morning Edition for National Public Radio where he always seemed to despise soccer. Although nominally positive, his attitude toward the sport shows throughout a story he wrote on the league for SI in 1983. The article titled “Show, Sex and Suburbs” treats the upstart MISL as a bemusing curiously rather than a legitimate sporting competition. Despite lasting fourteen seasons, it was one of only a few major articles on the league to appear in the magazine. To be fair, Deford recognized that the MISL’s focus on entertaining fans put it ahead of most leagues and that such efforts were “what a fully integrated sports promotional effort will henceforth resemble”[5] Generally, though, an undercurrent of condescension runs throughout the piece as when he described the teams as “6 little fellows to a side” and game action as chasing a “ladybug” around the pitch.[6] A story in the Washington Post was equally unsupportive declaring MISL “a schoolyard game that rubs the purist like fingernails on a black board” and quoting a fan who said they preferred soccer.[7] Throughout its existence the competition had trouble getting oddsmakers to create betting lines for the league something that might have attracted more interest to the games.

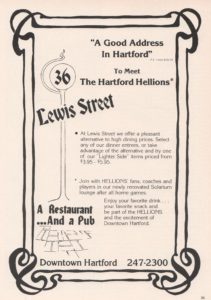

In some ways the initial decisions made by Hartford’s owners contributed to the problems that followed as the club never had enough capital to sustain itself. The Hellions faced other challenges, most of their own making, but others were due to bad luck or poor timing. They alienated state youth soccer organizations and deliberately floated a false story that the club was going to sign New York Cosmos striker Georgio Chinaglia. Chaos reigned within the organization as employees were hired, only to be let go with no explanation weeks later. Roster turnover was high, churning through at least thirty-three players in two seasons. The rudderless club was so disorganized that one player put himself on waivers (only to have it cancelled by Chipman) and Hubert Vogelsinger, who had been hired as Technical Director called Chipman “a maniac” and refused to work with him.[8] Bad luck also plagued the club, as when the roof of the Hartford Civic Center collapsed forcing the team to play “home” games in Springfield, Massachusetts, and New Haven, Connecticut. During the first match in the repaired space, the artificial turf came unstuck and tripped up players. Unpaid bills for wages, taxes and insurance piled up over the two seasons. When these debts were cleared after the club was sold for $275,000, it left about $110,000 to pay out to more than two hundred creditors. Groups that together were owed a combined $500,000 included the MISL, the University of Connecticut Marching Band and an at the time obscure regional cable network called ESPN.

Endnotes

[1] Maierhofer, No Money Down, 27.

[2] Maierhofer, No Money Down, 10.

[3] Deford, “Show, Sex and Suburbs,” 66.

[4] Sherman, “…But Still Cause to Cheer.”

[5] Deford, “Show, Sex and Suburbs,” 66.

[6] Deford, “Show, Sex and Suburbs,” 65.

[7] Richmond, “Indoor Soccer.”

[8] Condon and Lehr, “Hellions Misled Two Insurers…”

Other Sources

Tom Condon and Dick Lehr, “Collapse of the Hellion claimed many Victims.” Hartford Courant, September 1, 1981.

Tom Condon and Dick Lehr, “The Hellions: A Legacy of Vanity, Ineptitude and Debt.” Hartford Courant, August 30, 1981.

Tom Condon and Dick Lehr, “Hellions Creditors File Suit.” Hartford Courant, September 5, 1981.

Tom Condon and Dick Lehr, “Hellions Misled Two Insurers to the Tune of $100,000.” Hartford Courant, August 31, 1981.

Tom Condon and Dick Lehr, “State Begins Inquiry into Hellion’s Chipman.” Hartford Courant, September 15, 1981.

Frank Deford, “Show, Sex and Suburbs.” Sports Illustrated, February 28, 1983.

Fun While it Lasted, “1979-1981 Hartford Hellions” and “MISL (1978-1992).”

Dave Litterer, Steve Holroyd and Paul Reeths, Overview of MISL history and seasonal summaries at www.oursportscentral.com/misl/history.php.

Ronald P. Maierhofer, No Money Down. How to Buy a Sports Franchise. A Journey Through an American Dream. Indianapolis: Dog Ear Publishing, 2009.

Peter Richmond, “Indoor Soccer.” The Washington Post, February 8, 1981.

Howard Sherman. “…But Still Cause to Cheer.” Hartford Courant, December 2, 1979.

Kenn Tomasch, MISL attendance figures. Original website on hiatus, archives at www.archive.org