William E. Gill was a true sportsman. Mainly known throughout the New York metropolitan area for his cricket exploits, Gill also excelled at association football (soccer). A player of great talent, Gill was good enough to represent New York in a match against a representative side from Philadelphia in February 1894. Known as “W. E. Gill” in the local papers, he also captained the soccer and tennis teams of the Americus Athletic Association of West Hoboken, New Jersey, as far back as 1892, and served as treasurer of the organization.[1]

In these roles, Gill was able to see what worked and what did not work in the New York metropolitan soccer scene of the 1890s. Gill would put his thoughts to paper in a six-paragraph manifesto in the October 8, 1896, issue of the Amateur Athlete magazine.[2] To summarize, Gill was strongly against the formation of local leagues, as history showed they were financial failures that stunted the growth and acceptance of the game. Against this historical backdrop, however, one local league would form during the challenging soccer environment of the 1890s and eventually thrive. Created from the rubble of the first failed attempts at professional soccer in the United States, the National Association Football League (NAFL) operated, albeit not continuously, from 1895 until the formation of the first American Soccer League (ASL) in 1921.

The NAFL was a regional semi-professional league that operated in the northeast United States from 1895 to 1899 (NAFL I) and then from 1906 to approximately 1921 (NAFL II). Formed in New York, the NAFL initially contained teams only from New York City and northern New Jersey. During its second edition, membership was extended to include some of the top teams from eastern Pennsylvania. Although regional in geographical scope, the NAFL contained the top teams from many of the eastern soccer hotbeds of the time, including New York City, the Philadelphia region, and the New Jersey towns of Kearny, Newark, Paterson, Bayonne, and Jersey City. As such, the NAFL was considered one of the top soccer leagues operating in the United States.

Many early stars of American soccer – including many in the National Soccer Hall of Fame – played in the NAFL, including Pete Wilson, Archie Stark, Davey Brown, Robert Millar, Thomas Duggan, Tommy “Whitey” Fleming, and George Tintle. Many of the storied teams of the day were also members of the league, including the Kearny Scottish-Americans, West Hudson AA, Paterson True Blues, and the famous Bethlehem Steel FC. This essay focuses on when and where it all started, detailing the league’s founding in 1894/5 and its turbulent first season of operation during the spring and summer of 1895.

New York Metropolitan Area soccer before the NAFL

Although far from the cluttered sporting landscape we see today, there were many opportunities for eastern teams involved in the great kicking game to participate in organized competitions as far back as the mid-1880s. The successes and failures of these competitions contributed, in part, not only to the decision to form the NAFL but ultimately to the NAFL’s success.

Riding the wave of the 1880s immigration boom, New York Metropolitan Area soccer in the 1880s and early 1890s was a period of tremendous change. The founding in 1884 of the American Football Association (AFA) Cup competition, the first inter-city soccer competition in the US, was followed by the formation of several local New Jersey and New York leagues, and participation in two attempts on the east coast at forming fully professional leagues. A few of the New York metro area leagues that operated around the time of the NAFL will be summarized below. As was a recurring theme in the history of soccer in this country, the momentum from the 1880s could not be maintained, and by the late 1890s, the organized game was struggling in even previously strong eastern cities and towns.

New Jersey State Football Association and League

A New Jersey State Football Association was active as far back as 1886. Not much is known of the early years of the Association although a picked eleven from the Association defeated a similar eleven from the New York Association 6-1 at Prospect Park, Brooklyn, on April 24, 1886.[3]

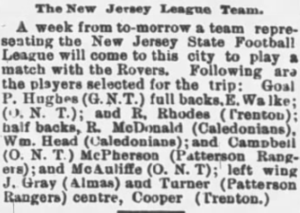

A New Jersey State Football League (NJSFL) existed as early as 1889 and included many of the eastern powerhouses of the time such as Kearny Rovers, Trenton FC, Newark Almas, Newark Caledonians, Paterson Thistles, and Clark ONT.[4] The first president of the league was William Nunely of the Tiffany Rovers, a team composed of employees of the Tiffany & Company plant in Newark.

The Paterson Daily Guardian wrote in 1889 that the object of the Newark-based NJSFL “should be the raising of a fund for charitable purposes. The clubs in the League shall play a series of games for the championship of the State, and the gate money collected at each match over and above all actual expenses shall be donated to some charitable institution in the town in which the match is played.”[5] This commitment to philanthropy was genuine, as expressed in July 1889 when the NJSFL played a benefit match between players from Newark and Paterson for the sufferers of the great Johnstown flood in Pennsylvania which occurred several weeks earlier. In addition to NJSFL league games, contests were also arranged for NJSFL-picked elevens to meet teams from Fall River and Pawtucket, helping to stoke regional rivalries.

Little is known about this league, including the years of operation and a full list of champions. Records do show the champions for the 1889/1890 season were the Newark Caledonians, who included in their lineup Neil Munro, an international star capped twice for Scotland and a goal scorer in the April 13, 1889, Scotland victory over England.[6]

Shelton (Sheldon) Cup

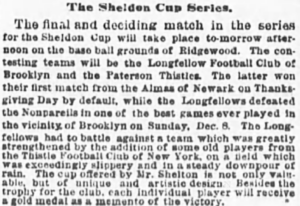

A brief tournament was conducted during the winter of 1889 between select New York and New Jersey clubs for the Shelton (a.k.a., Sheldon) Cup. A cup of “unique and artistic design” was offered to the winning team as well as a gold medal for each player given “as a memento of the victory.”[7] The games were played at the Ridgewood Base Ball Ground, Ridgewood, New York.

The initial schedule called for a Thanksgiving morning encounter between Longfellows of Brooklyn and Nonpariel Foot Ball Club of New York, and an afternoon battle between New Jersey rivals Paterson Thistle and Newark ONT. The final was to be played “on the first convenient day.”[8]

The Longfellow – Nonpariel match was pushed to December 6 and was apparently worth the wait. The Longfellows won a rainy encounter over a Nonpariel team bolstered by several members of the strong New York Thistle club. The opponent of Paterson Thistle was switched from Clark ONT to Almas of Newark. When Almas failed to appear for the game, Paterson won by default.

The long-anticipated final at the Ridgewood grounds was scheduled for December 22 but now Paterson Thistle failed to appear for the contest. The Longfellow forwards kicked off, sent the ball through the goal, and then proceeded to wait 45 minutes in vain for the Paterson club to arrive. The New York Sun commented that “spectators and players alike were disappointed as everybody had expected to witness a good, close game.”[9] Unfortunately, teams not showing up for scheduled encounters was a common occurrence during this time period and contributed to the inability of soccer to establish a firm foothold among the sporting public.

Passaic County League

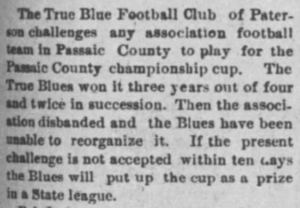

The Passaic County League was a popular competition that operated in the Passaic/Paterson New Jersey region from 1890 to 1894. The competition was dominated by the Paterson True Blues and Paterson Thistles, two local rivals who also achieved success on state and regional levels. While the league was open to “any clubs playing within a radius of Passaic County,” only the Thistles, True Blues, Paterson FC, and the young Paterson Violets ever competed in the league.[10] In an attempt to prevent member clubs from temporarily recruiting ringers for important matches, the league stipulated that players must be residents of Passaic County for at least 30 days. Again, little is known of this league other than what can be gathered from sporadic newspaper accounts. For the season ending in March 1891, the True Blues won the title by being the first among the leagues three teams that season — the True Blues, Thistles, and Paterson FC — to amass five points. The Thistles captured the silver cup and medals the following year only to be edged out by True Blues for the 1893 championship.[11] The 1894 Cup was again won by the True Blues, who dominated the Thistles 4-1 in a deciding fifth-round contest where “a considerable amount of money changed hands,” according to the Paterson Call.[12] The True Blues were one championship away from having the trophy become the permanent property of the club.

In December 1894, the Passaic County Football League called a meeting at Helvetia Hall, Paterson, and invited the True Blues, Thistles, Crescents, Rangers, and the “Paterson League” team to participate in the upcoming tournament. The Paterson Thistles could not enter the league as “a number of players have been playing professionally.”[13] Little interest was shown in the league from other teams and in January the True Blues, having been unsuccessful in attempts to reorganize the league, issued a challenge to any Passaic County club to a contest for the cup. The True Blues left the challenge open for ten days, “but if it is not accepted within that time they will consider the trophy their property and probably put it up for a State League contest or Junior competition next season.”[14] There are no records to indicate any team accepted the Blues’ challenge, and the once-popular league died a natural death.

Willard Park League

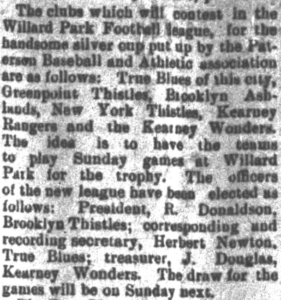

The Paterson area hosted the ambitious but short-lived Willard Park League (also known as the Willard Park Cup and Willard Park series) in 1893. With the association game at the height of its popularity in Paterson, the combination of the Willard Park League and the Passaic County League ensured that Paterson soccer fans did not have to travel far to experience high-level competition. The league consisted of Sunday contests between eleven New Jersey- and New York City-based clubs: the Paterson True Blues, Paterson Thistle, Centreville AC, Newark Caledonians, Greenpoint Thistles, Brooklyn Ashlands, Harlem Red Stars, New York Thistles, Americus of West Hoboken, Kearny Rangers, and Kearny Wonders.[15]

The league was arranged primarily on behalf of the Willard Park Organization by Herbert Newton, the hustling manager of the True Blues. Although the league was based out of Paterson with Newton the driving force, league officers included members of Greenpoint Thistle and Kearny Wonders. The Paterson Baseball and Athletic Association donated a “handsome and valuable silver punch bowl” for the league champions. The league was different in that “the arranging of the rules to govern the cup contests and the fixing of the schedule was left entirely in the hands of the clubs entering the tournament. The only condition imposed by the association is that the games shall be played at Willard Park on Sundays.”[16] However, records show that some if not all games were played under the American Football Association rules penned in nearby Newark.

Little is known of the league, including who was the league champion. The scant newspaper coverage indicates the league may not have completed its inaugural season. Although the competition between the True Blues, Caledonians, and Kearny clubs was fierce, several games with double-digit goal differentials were recorded involving the lesser-quality clubs. The league format may have contributed to this problem. The New York-based teams may have simply lost interest in traveling to Paterson for a humbling defeat, with no home contests on the horizon. Gill, in his manifesto, commented on this exact problem:

The first few league games are played with all the good players condensed into one or two clubs and as soon as it is evident which is the winning club, the others cancel their engagements, which practically kills the league, for no more receipts come in and the game is dead before the season if half over.[17]

New York State Football Association and League

A New York State Football Association was active as far back as 1886 under the direction of Secretary H. Manley. The goal of the initial five-team association was to organize a series of home and home matches against other state associations. A representative team was selected from the player pool after a series of matches played between teams in the association and consisted of four players each from the Riversides and Pilgrims, and two players each from the West Side and West Brighton clubs.[18] One game was documented, a 6-1 defeat to New Jersey in April 1886.

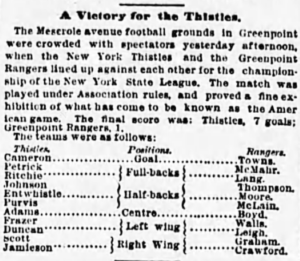

A short-lived New York State Football League (NYSFL) existed as early as 1890, but its first year of operation was a dismal failure due to three of its five clubs dropping out due to issues with league management. As a result, the schedule was never completed. Efforts by league management in December 1891 were more fruitful, with ten clubs joining the fray: Brooklyn Football Club, Longfellows, Comrades, and Atlantics, all from Brooklyn; Thistles and Rangers from Greenpoint; West Side Shamrocks and Thistles of New York; Long Island City Football Club and New Rochelle Football Club. The New York Sun reported the NYSFL “championship will be decided on a percentage basis somewhat similar to the plan of the National Baseball League.”[19] The 1891/92 NYSFL season was considerably more successful, with nine clubs still competing as of February 1892.[20] New York Thistle won the 1891/92 league championship, winning a match on March 13, 1892, against West Side Shamrocks, ”for the championship of New York,” ”under the rules of the New York State Football League.”[21]Thistle was the strongest New York team during this period, with second-place finishes to their credit in the American Football Association Cup competitions in 1892 and 1893. Unfortunately, the NYSFL did not reorganize for the 1892/93 season.

American Football Association

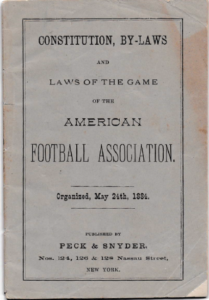

The American Football Association (AFA) was organized on May 24, 1884, at Caledonian Hall in New York City, and through its annual cup competition provided a regional tournament open to all affiliated teams independent of their participation in local leagues. The AFA Cup competition was immensely popular and continued – with a similar interruption that coincided with the NAFL – until 1924. The AFA Cup’s importance was elucidated by C. K. Murray in the 1910 Spalding Soccer Guide, where he wrote “it has always been the fondest ambition of every association foot ball club to win the American Cup, and the ‘final’ is looked upon as the event of the season in the ‘soccer’ foot ball world.”[22] Many of the early eastern regional soccer rivalries can be traced back to AFA Cup rivalries, especially between teams from the New York metropolitan area and the “Down East” region consisting of Fall River, MA, Pawtucket, RI, and others. New Jersey clubs were champions of the AFA three times between 1885 and 1894, with the other seven champions hailing from “Down East.” The cup would return to New Jersey in 1894 when Newark Caledonians defeated Pawtucket Free Wanderers. Although it can be argued these “cradles” provided the bulk of the tournament’s entries, these regions played a vital role in the development of the domestic game and usually fielded the most dominant teams.

Perhaps the AFA’s greatest contribution in these early days was the standardization of rules used in the AFA Cup competition. The AFA published an annual which documented its Constitution and By-Laws, Laws of the Game, Cup Competition Rules, and Regulations for Forming a Club. As far back as 1886, the New York Herald wrote “the American Football Association’s rules are becoming very popular in neighboring towns. Besides the clubs in the Association Paterson has a second team, the [Clark Thread Mill] O. N. T. club a second team, and other clubs are in course of formation.” Before the AFA, there was no central authority, and regions might play under different sets of rules. For example, in 1884 the Fall River Daily Herald published the Laws of the Lancashire Association, which reflected the city’s ties to that region in England. The Lancashire Laws were a word-for-word recounting of the England Football Association’s 1881 Laws of the Game that omitted revisions made in 1882 and 1883.[23] Down in Paterson, an 1883 dispute between the True Blues and Thistle had local soccer pioneer Tommy Tuffnell looking to submit the matter “to the Scottish Football Association, or the editor of any New York Sporting Newspaper.”[24] The AFA was somewhat successful in filling these voids. Curiously, the AFA appeared to favor the Scottish Football Association as the ultimate rule authority, not the English FA. [25]

Although successful in providing limited administration and high-level competition to a burgeoning soccer nation, the AFA was far from a harmonious organization. Power struggles were common between the central powers in Newark and those with ambitions in Fall River and Paterson. Control of the organization was finally wrestled away from Newark in May of 1892 by the Down East teams, who for the past several years were the dominant force in American soccer. The victory would be short-lasting, with the AFA “freezing out” Down East clubs from the 1896–97 edition of the tournament before the AFA itself ceased operations after the 1897/8 competition until its re-emergence in 1906.[26]

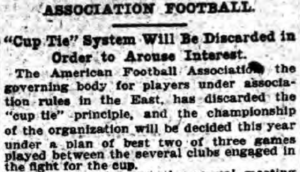

The AFA’s attempt in 1896 to create a Sunday league in addition to the regular cup tie series was unsuccessful and drew the ire of W. E. Gill and many others.[27] The AFA’s goals were noble, however, arguing “when a team was beaten in their respective rounds they were out of the competition altogether, and naturally their followers lost all interest in the game; but with the formation of the league it will keep all the clubs before the public, as each team will play home and abroad matches that will carry them through the football season.”[28] Ultimately voted down, Gill stated, “We certainly commend the two clubs voting against the formation of a league as we do not consider it in the interest of the game here.” The tournament format was modified that year to include a best two-of-three series and ended with a four-game donnybrook between the True Blues and Philadelphia Manz, in which Manz captured Philadelphia’s first AFA Cup. Of the competitions organized up to that point, the AFA Cup tournament was most in line with Gill’s vision for expanding the game. He wrote:

The only way to make the game a go here is to organize clubs, arouse local enthusiasm, spread the game over as much territory as possible, play home and home matches and you will find that your little gates will be sufficient to meet the ordinary expenses of a team or club, until such times as the Sunday half-holiday is universal. Then and not till then will a league be a benefit to the game.[29]

The professional football leagues

Gill’s vision to grow the game organically – with gate receipts only being charged to sufficiently cover ordinary club expenses – was not universal. Professional association football made its United States debut in 1894 with the creation of two rival leagues on the east coast, the American League of Professional Football Clubs (ALPF) and the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF). A large volume of research has been conducted on these two leagues, in particular, in From Football to Soccer: The Early History of the Beautiful Game in the United States (2021), by Brian D.Bunk, “The AAPF and the ALPF: The beginnings of professional league soccer in the United States” (2018), by Ed Farnsworth, and “The First Professional Soccer League in the United States: The American League of Professional Football (1894)” (2000), by Steve Holroyd.

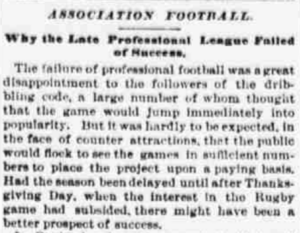

The ALPF was formally introduced on June 19, 1894, by local baseball magnates “to enable them to keep their players in trim through the winter,” although in hindsight most agree it was simply an attempt to squeeze revenue from their stadiums during the baseball off-season.[30] The league was composed of “the six leading Eastern clubs of the National Base Ball League:” Boston, Baltimore, New York, Washington D.C., Brooklyn, and Philadelphia.[31] By all accounts, the league was a failure, with operations ceasing on October 20, 1894, less than two weeks after its first contest. The ALPF made many mistakes in its short tenure, among them neglecting the major soccer hotbeds and scheduling mid-week games that the primary fan base – urban mill workers (factory hands of Scotch or English birth) – were unable to attend due to work commitments.

The existence of the AAPF was formally announced on August 23, 1894, although newspaper accounts stated the league had been in the process of formation for over six months and was “practically organized for six weeks.”[32] The AAPF initially announced a six-team league featuring clubs from Paterson, Newark, Trenton, Philadelphia, New York, and Brooklyn, but it does not appear the New York and Brooklyn clubs ever took part in league play. Contrary to the ALPF, the AAPF was founded by individuals with extensive soccer experience. Clement Beecroft, former president of the Pennsylvania Football Union, was the driving force behind the league. The AAPF included the major soccer centers in New Jersey and Eastern Pennsylvania and only scheduled Saturday and holiday fixtures. Furthermore, the limited geographic scope of the league aimed to take advantage of existing local rivalries.

The AAPF envisioned a two-part season, the first lasting from the end of September through January 1 and the second running from March through May. The second session never took place, with the last recorded game being held on Christmas Day, 1894. Records show the Philadelphia and Paterson clubs were the class of the fall session, while Newark was competitive, and Trenton was outmatched. Trenton bowed out after three lopsided defeats, providing another example of Gill’s manifesto.

Although short-lived, the two professional leagues were successful in causing considerable turmoil in local association football circles. Several later recollections of the period mention the advent of professionalism as the main reason for the decline of soccer from the late 1890s until the mid-1900s. The Fall River papers worried that the local professional players “will suffer so badly from [a] swelled head that they will decline to sign contracts that do not provide for princely salaries.”[33] In response to the ALPF league announcement, the New England Football League met in August to discuss plans to “offset the operations of the national league of football clubs [ALPF].” The Fall River Globe was concerned the poaching of local talent would “give the New England League a hard shaking up, and perhaps interfere with local football to some extent.”[34]

The league’s quick demise did not solve all their problems, as some of the ALPF teams stayed together after the October 20th collapse and November 1st date signifying the last official payment to the players. The statement issued when the league announced its closing referenced the formulation of “a new association ready for spring work.”[35] With teams representing Boston and Denny Shay’s Brooklyn club participated in the Fall River Mayor’s Cup and were playing as late as April 1895, perhaps hopes were that the league owners would right the ship and carry out the spring portion of the initial schedule.

Down in Newark, in defense of a perceived encroachment of its territory, the AFA prohibited any player who signed a professional form from playing in any AFA contest. The AFA caught wind of a “clever plan on the part of the National League [ALPF]” to “induce association players to join the league” by offering competitive salaries to compete in its three-month season, whereas afterward, the players would be “in readiness to participate in the association contests.”[36]

This AFA’s boycott was predictably met with animosity in New England, which was home to five of the AFA’s strongest teams.[37] Fall River had a large number of participants in the two upstart professional leagues, with 13 Fall River players alone under contract with the Brooklyn ALPF squad. Many felt that the influence of the established professional baseball league would have a positive impact on the local, sometimes haphazard, soccer scene. Others felt the ALPF would operate in the period before the AFA contests were fully underway and that “the baseball league ought to be thanked for its energy, instead of having cold water thrown on its scheme” by the “so-called American association.”[38]

The AAPF was responsible for more localized churn. The Willard Park League, Passaic County League, and American Association Football League (see below) all ceased operations around the time the professional leagues commenced play. The Paterson Thistle – a direct casualty – lamented about their “illegal” status for rostering players who had signed professional forms. The impact on the player was also profound, with one newspaper reporting, “association players are hustling for engagements as professionals on the new teams.”[39] Suddenly, capturing the Passaic County League Cup was not nearly as desirable as signing a contract for a professional team in a major urban center, and the local game suffered.

American Association Football League

The league most pertinent to the founding of the NAFL was the American Association Football League (AAFL), organized in February 1894 at Schillinger’s Hall, New York City.[40] The AAFL’s founding was viewed favorably, with the New York Sun reporting “followers of the Association game have increased surprisingly in New York and vicinity for the last few seasons, and they claim that the new League is the only requirement needed to the permanent success of the sport.” Further, it was “thought that the competition thus engendered will rivet the ‘dribbling code’ in the esteem of the football community.”[41] Folks in Fall River had a different view, wryly claiming that the league was created so New York-area players could collect medals and trophies without having to face teams from Spindle City.[42]

The league agreed to maintain a Sunday schedule “on enclosed grounds” with “the competing teams to receive all gate receipts, except 25 [later changed to 20] percent gross, which will go to the league.” Joseph Cleary, of the West Side Shamrocks, was an early benefactor of the league and offered up “a challenge cup valued at $100” to the winning side.[43] The winners of the Cleary Cup also received gold medals, with silver medals awarded to the runners-up.

During enthusiastic early discussions, it was thought “that at least a dozen affiliated clubs will enter teams.”[44] In addition, “the Teutonic Rovers, of the steamer Teutonic also applied, but as they could only play here one Sunday in a month, the league did not see how they could adjust their schedule in justice to the other clubs, and their application was rejected.”[45] By late April 1894, league enrollment was limited to only six teams, something W.E. Gill could have predicted. Sporting Life reported, “the football team of the Acorn AA has gone out of existence. This is the third organization that has dropped out of the American Association League on account of their teams not being strong enough.”[46] Six teams appear to have completed the inaugural AAFL season: Americus AA of West Hoboken (now Union City), New Jersey; Red Star FC of Harlem, New York; Ashland FC of Brooklyn, New York; Sylva AC of Jersey City Heights, New Jersey; West Side Shamrocks of New York, New York; and the Somervilles of Somerville New Jersey.[47] The Paterson Thistles and Bayonne Centrevilles, mentioned as early league members, appear to never have joined.

By all accounts, the AAFL was a contentious league characterized by protests, violence, and an unusually high number of disputes over referee decisions. The chaos often spilled over into the weekly meetings, causing one newspaper to comment on the “tendency on the part of some members of the league to degrade themselves by casting personal reflections upon certain representatives.” The league management decided to “punish the offenders in the future by instant dismissal from the league.”[48] Gill, the Americus league delegate, had a front-row seat to all the drama. Protests were so commonplace that the league eventually ruled that no protests “would be taken up unless a two-thirds vote of the representatives should so decide.”[49] A game between the Americus and West Side Shamrocks was protested on the “ground that the Americus team made a goal by the interference of a policeman with Johnson, the goalkeeper of the Shamrocks.”[50]

Violent play was also commonplace in AAFL league fixtures. A match between the West Side Shamrocks and Harlem Red Stars at Leo Park, Long Island, “resembled at times a regular free and easy street fight. Rough and foul playing characterized the game throughout, and several of the players were injured.”[51] Donnelly of the Shamrocks, elected president of the Shamrocks in August 1891, and Anderson of the Red Stars were involved in an altercation where “Anderson’s arm shot out and he landed a hard blow on Donnelly’s mouth. Blood spurted in all directions. When Donnelly recovered, he found that he was minus a tooth.” The match ended with yet another protest, with the New York Sun reporting the “affair will be brought to the attention of the Association’s Council tonight. A lively time is expected.” In another game involving the Shamrocks, George Johnstone, captain of the Sylva AC, “met with an accident which will disfigure him for life.”[52] The Jersey City News shared the gory details:

Dr. Hecht, who resides near the ground, was immediately summoned. He found Johnstone’s nose broken in two places and lacerated up the right side to the bridge, which necessitated thirteen stitches. Johnstone stood the pain of the operation without wincing.[53]

Americus AA, representing the Americus Hook and Ladder No. 2, in West Hoboken, NJ, won the inaugural AAFL championship, and with it, possession of the Cleary Cup. W.E. Gill, a member of the champion eleven, was also treasurer of the Hook and Ladder. Second place went to Ashlands, of Brooklyn, and third place to Harlem Red Stars.

Why was there no second AAFL season? Perhaps the introduction of the ALPF and AAPF caused interest in the troubled league to wane, or perhaps it simply died a natural death. What is known is that W. E. Gill, and several others, learned a lot about how not to run an association football league.

Notes

[1] The Americus AA was an organization composed of the Volunteer Fire Department of the Americus Hook and Ladder No. 2, in West Hoboken, NJ. Organized in June 1887, several of the founding members of the Hook and Ladder played for the football team.

[2] “Association Football,” The Amateur Athlete, October 8, 1896, 4.

[3] “Football,” The Newark Sunday Call, April 25, 1886. 1.

[4] “Sports Indoor and Out,” Paterson Daily Guardian, Tuesday, March 19, 1889; “Items for Sportsmen,” The Paterson Daily Guardian, Wednesday, September 18, 1889, 2.

[5] “Sports and Pastimes,” Paterson Daily Guardian, (date and page unavailable)

[6] “Football at Ridgewood,” New York Herald, September 1, 1890, 6; https://www.scottishfa.co.uk/players/?pid=113564.

[7] “The Sheldon Cup Series,” The New York Sun, Saturday, December 21, 1889, 4.

[8] “Notes of the Elevens,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Sunday, November 17, 1889, 2.

[9] “Football,” The New York Sun, Monday, December 23, 1889, 6.

[10] “Interesting Football Notes,” The Paterson Morning Call, October 30, 1891, 1.

[11] “The Thistles Will Be Champions,” Paterson Daily Guardian, January 26, 1892.

[12] “True Blues Win The Cup,” The Paterson Call, May 14, 1894, 8.

[13] “Sporting Miscellany,” Paterson Daily Guardian, November 21, 1894, 8.

[14] “Columbias Score Two,” Paterson Daily Guardian, December 8, 1894, 1; “Sporting Gossip,” Paterson Daily Guardian, January 15, 1895, 1. The Paterson League Team was the name given to the Paterson team which participated in the American Association of Professional Football Clubs (AAPF).

[15] “Notes of Sport,” Paterson Evening News, Saturday, October 7, 1893, 1.

[16] “Coming Sporting Events,” The Paterson Morning Call, Saturday, October 7, 1893, 1.

[17] ”Association Football,” The Amateur Athlete, October 8, 1896, 4.

[18] “New York State Football Association,” The New York Sun, Friday, March 26, 1886. “The State Football Team,” The New York Times, April 18, 1886, 7.

[19] “Meeting of the New York State League,” The New York Sun, Monday, December 14, 1891, 6.

[20] ”A Tie at Football,” The New York Sun, February 1, 1892, 5.

[21] ”Odds and Ends of Sport,” The New York Sun, March 12, 1892, 4; ”Football Notes,” The New York Sun, November 4, 1892, 4; “A Victory For The Thistles,” The New York Sun, Tuesday, February 23, 1892, 4. The New York Thistle had a fantastic curling team as well.

[22] “History and Progress of the American Football Association,” C. K. Murray, Spalding’s Official Association Soccer Foot Ball Guide, 1910-11, ed. Thomas W. Cahill (New York: American Sports Publishing Company, 1910), 27.

[23] “Football: Laws of the Lancashire Association,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 17, 1884, 4. Ed Farnsworth, Tom McCabe and Kurt Rausch would add in “The Noxious Scottish Weed”: Early North American soccer and the Laws of the Game, Society for American Soccer History, last modified March 31, 2022, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/the-noxious-scottish-weed-early-north-american-soccer-and-the-laws-of-the-game/, that at first glance, it appears the Daily Herald lists only 14 Laws of the Game rather than the 15 in the 1881 FA Laws. But an error in the numbering of the list of Laws as printed by the Daily Herald following Law 13 sees the number 13 attributed twice. Law 14 in the 1881 FA Laws of the Game is misnumbered as 13 by the Daily Herald, resulting in Law 15 being misnumbered as Law 14.

[24] “Last Saturday’s Football Match,” Paterson Daily Guardian, October 19, 1883.

[25] Ed Farnsworth, Tom McCabe, and Kurt Rausch considered why the first soccer associations in North America favored the Scottish FA over the English FA as the source for their Laws of the Game in “The Noxious Scottish Weed”: Early North American soccer and the Laws of the Game, Society for American Soccer History, last modified March 31, 2022, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/the-noxious-scottish-weed-early-north-american-soccer-and-the-laws-of-the-game/,

[26] “A Freeze-Out,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 27, 1896. 7.

[27] “The Dribbling Code,” The New York Sun, Sunday, October 11, 1896, 7.

[28] The Amateur Athlete, October 1, 1896, 4.

[29] “Association Football,” The Amateur Athlete, October 8, 1896, 4.

[30] “Manager Irwin’s Latest,” The New York World, February 25, 1894, 36.

[31] “Professional Football,” The Philadelphia Enquirer, June 20, 1894, 3.

[32] “A professional Football Association,” Paterson Evening News, August 25, 1894, 5.

[33] “Is football to become as popular as baseball?” Fall River Daily Herald, February 28, 1894, 4.

[34] “Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, August 27, 1894, 8; “Local Football Kickers Get Good Jobs,” Fall River Globe, August 25, 1894, 7.

[35] “Professional Football Clubs End Their Season,” The Boston Globe, October 21, 1894, 4.

[36] ”Football War on the Tapis,” The Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago, Illinois, September 17, 1894, 8.

[37] “League Players Barred,” The New York Times, September 18, 1894, 3.

[38] “Fair Play Asked For,” The Boston Globe, September 19, 1894, 3.

[39] “Ashlands vs. Red Stars,” The Standard Union, Brooklyn, New York, July 12, 1894, 8.

[40] “The American Association Football League Organized,” New York Sun, Thursday, February 15, 1894, 8.

[41] “A New Football League,” New York Sun, Tuesday, February 20, 1894, 8.

[42] “New Football Association,” Fall River Globe, February 16, 1894, 7. Keep in mind the “Down East” clubs captured the AFA Cup every year during the period 1888 to 1894. This arrogance was well earned.

[43] “The American Association Football League Organized,” New York Sun, Thursday, February 15, 1894, 8.

[44] “A New Football League,” New York Sun, Tuesday, February 20, 1894, 8.

[45] “Association Football League,” The New York Herald, Wednesday, March 1, 1894, 12.

[46] “Punts and Passes,” The Sporting Life, April 14, 1894, 7.

[47] “Association Football Men in Good Working Order,” The New York Sun, Tuesday, April 24, 1894, 5.

[48] “Association Football Men in Good Working Order, The New York Sun, Tuesday, April 24, 1894, 5.

[49] “Football Men Disputing,” New York Herald, Tuesday, April 3, 1894, 13.

[50] “Two Football Games at Americus Park,” The New York Sun, May 7, 1894, 6.

[51] “Fists As Well As Feet,” The New York Sun, Monday, April 2, 1894, 6. The West Side Shamrocks were one of the more colorful teams in the AAFL The Shamrocks were organized on the “west side of the city above Fourteenth Street” in 1891. The area they represented, the upper portion of Greenwich Village and Chelsea, included a large Irish population centered on the West Side piers and associated support structure. The club’s offices, at 458 Ninth Avenue, New York, were on the southern border of the infamous Hell’s Kitchen section of Manhattan. The Shamrocks were known for their rough play and were involved in more than one odd situation during their brief history. On Christmas Day 1891 the Shamrocks travelled to Newark to meet the Caledonians only to be met by a tipsy Caledonian team who indulged in too much “Christmas cheer” prior to the game. Captain Cleary pulled the team from the field out of frustration after only a few minutes of play. (Football, The New York Sun, Tuesday, December 29 1891, Page 4) Two months prior, playing against a team from the steamship City of New York, sneak thieves broke into the sailors dressing room at the Oak Cliff Hotel in Weehawken NJ and “carried away anything of any value.” (English Tars Try Their Hand, The New York Sun, Monday, October 26 1891, Page 4)

[52] “Adams is a Savage Kicker,” The New York Sun, Monday, April 30, 1894, 6. My teenage son still talks about this article.

[53] “Two Players Injured. Adames Breaks Captain Johnstone’s Nose and Kicks Dockray’s Face,” The Jersey City News, April 30, 1894, 3.