At the end of the nineteenth century, Pawtucket, Rhode Island was a bustling industrial city. Like many nearby communities, including Fall River, Massachusetts, Pawtucket’s citizens played soccer. Teams from the city took part in local and regional competitions as well as the American Cup. Pawtucket sides took home the Cup and, along with it, the de facto national championship in 1893 and 1911. On April 14, 1894, a match report about the Pawtucket YMCA’s junior team noted that a YMCA player named Fred Watson had accidentally kicked an opponent, breaking his leg. A few months later the Fall River Daily Herald reported that Pawtucket YMCA’s senior squad had signed Oliver Watson.[1]

Notices of matches and signings were commonplace and even the fact that the two Watsons were brothers did not make the articles exceptional. What is significant however is that Fred and Oliver were African Americans. The Watson brothers are the earliest documented African American soccer players in the United States. The pair was born in Rhode Island, Oliver in 1872 and Fred in 1875. They also had three older brothers who did not seem to play soccer, although Eugene (b. 1870) was a musician and newspaper reporter who was active in politics and civil rights work. Over the next decade, Oliver and Fred lined up for several different teams and achieved a number of important milestones in the history of soccer in the United States. Oliver is the earliest known African American player to compete in a senior club match. He was also the first to play and score in the American Cup competition. In spring 1901, the brothers became the first African American soccer players to win a league championship. In fall 1901, Fred became the first African American to play in a professional soccer league game.

“He was the first colored player ever seen in this city”

As the 1894-95 season got underway, the New England League found itself in a state of flux. The effects of the great economic crisis known as the Panic of 1893 were felt in the mills and factories of Pawtucket and Fall River. The exodus of players to the short-lived American League of Professional Football (ALPF) — the bulk of the Brooklyn squad and much of the Boston team were made up of some of the area’s most talented players — had shaken the local league. That these players were so attractive to the baseball-backed professional league was understandable. Fall River sides had lifted the American Football Association’s American Cup trophy every year since 1888 before Pawtucket Free Wanderers took their turn as champion in 1893.

The period of American Cup dominance by Fall River and Pawtucket sides mirrored the region’s emergence as the strongest center of soccer in the United States. Attendance for high profile league matches in the region was among the largest yet seen in North America. Beginning with Pawtucket in 1890, American Cup finals were sometimes staged in New England League territory. The AFA’s ban of ALPF-signed players from participation in the American Cup was another blow when the ALPF collapsed just as the New England League’s 1894-95 season got underway. With former ALPF professionals unable to return to New England League teams, both the quality of league play and the prospects of its teams in the AFA tournament were affected, and interest in matches waned along with gate receipts.[2]

On September 26, 1894, ahead of the start of the 1894-95 New England League season, the Fall River Daily Herald reported that league side Pawtucket YMCA had signed thirteen players, including reserve team forward Oliver Watson.[3] On December 22, 1894, Watson made his first start for the senior squad.

On that day, the Pawtucket YMCA team traveled to Fall River to face the Fall River Olympics in a New England League match at the South End Grounds. Newspapers reported attendance for the game was light. The YMCA team fielded a weakened side with four substitutes, including Oliver, in place of regular starters. The home team quickly tallied five first-half goals. “The Olympics then let up,” the Fall River Daily Globe reported, “and the visitors, taking advantage of the chance, braced up and scored.” The Fall River Daily Herald said of the goal, “The Pawtuckets, on a rush, succeeded in getting one, Watson putting the ball through.”[4] Despite YMCA’s comeback, the Olympics finished the game 8-2 winners.

Confusingly, the Daily Herald reported Watson played at right wing, while the Daily Globe had him at left wing. As was typical at the time, neither report included a first name or first initial for the goal-scoring winger. But the Daily Globe did report:

Watson, a colored man, played on the wing for the visitors. He was the first colored player ever seen in this city, and during the game he caused no end of fun by his funny talk and antics.[5]

A match described as “too one-sided to be interesting” and “a complete walkover” in fact was historic. Not only was Oliver Watson the first African American soccer player to appear in Fall River, he was the first African American player in a senior league soccer match in the United States.

“The gentleman of color”

Except for a Christmas Day exhibition game, Watson’s next mention in match reports after the New England League contest against Fall River Olympics was for an AFA Cup second-round matchup against Fall River East Ends, making him the first African-American player to appear in a US tournament with claims to representing a national championship. Winners of the American Cup in 1891 and 1892, East End had a bye in the first round of the tournament’s 1894-95 edition. The YMCA team had advanced to the second round after pulling off a surprising 2-1 victory over Fall River Rovers.[6] But, as was so often the case, the harsh New England winter wreaked havoc on both the League and AFA Cup schedules and the second-round cup tie’s original January date was postponed for two months.[7]

On March 9, 1895, the YMCA team won a home victory, coming from behind to dispatch the East Ends in “a remarkably fast game.” The Fall River Daily Globe match report highlighted Watson’s play. Leaving behind previously racist descriptions, the newspaper now referred to Watson as “the gentleman of color” and praised his passing ability. With his team trailing 3-2 at the start of the second half, Watson scored the equalizing goal. The Daily Globe reported,

The home team from a fine passing streak got behind the half-backs, and Watson, getting the ball, made a break for goal. From a long shot on the right he put one behind Cornell. A great shout went up, and both teams went into the fray in the hottest style of play.[8]

The Pawtucket Evening Times described Watson’s goal as coming from “a fine high kick from the left wing, the ball just sneaking into the upper corner.” The YMCA team soon took the lead and then “passed, dribbled and punted by their opponents like fiends.” Watson led the way. The next goal scorer “received the ball from Watson” before sending “it into the cage.” The final tally came “after a fine run down the field by Watson,” who “passed splendidly” to assist the goal. With the 6-3 win, the YMCA team headed to the American Cup semi-finals to face Pawtucket Free Wanderers, hometown rivals and winners of the 1893 American Cup. [9]

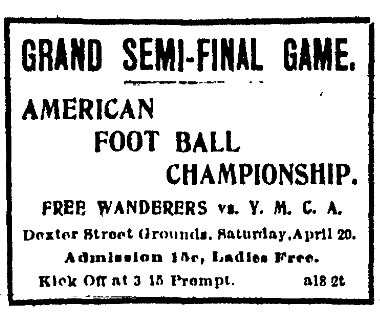

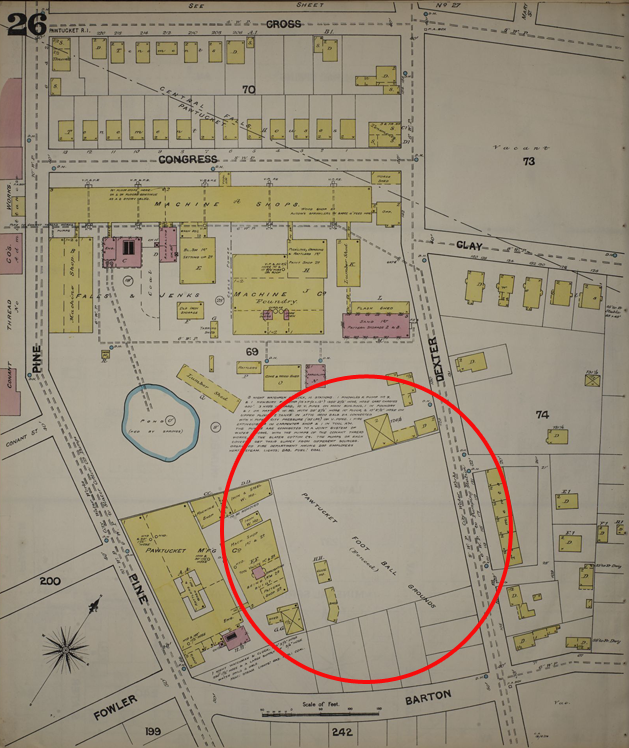

On April 20, 1895, the two Pawtucket sides met at the Free Wanderers’ Dexter Street Grounds. A formidable aggregation, the Free Wanderers were favored to win although they had lost the Pawtucket Mayor’s Cup to the YMCA squad the previous spring. The YMCAs were relative newcomers, having joined the New England League the previous season. The Pawtucket Evening Times noted that the Free Wanderers’ supporters expected their team “would easily overcome their young opponents” to advance to the Cup final.

Such expectations seemed fulfilled when the home side dominated the first half of play, which finished with the Free Wanderers enjoying a 1-0 lead. The Wanderers’ fine play continued after the start of the second half, but soon the momentum gradually shifted toward the visitors. Twenty minutes from full time YMCA managed to equalize. Newly invigorated, “the Y.M.C.A. boys” now forced the Free Wanderers “to act strictly on the defensive.” As the Evening Times match report described, soon “the loud cheering of the crowd” made clear Watson had scored to “put the black and gold in the lead,” his second goal in as many AFA Cup appearances. The jubilation of the YMCA supporters was short lived when moments later the Free Wanderers equalized. Back and forth play swung — “the rivalry between the teams was intense and the excitement of the players at the highest pitch” — before in the dying seconds the Free Wanderers claimed a handball in front of the YMCA goal. But the resulting free kick was saved and the match finished tied at 2-2.[10]

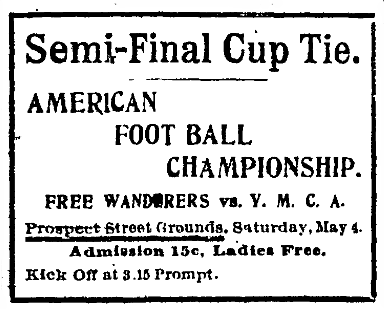

The teams met in the replay at the YMCA home grounds two weeks later on May 4. Watson once more was at right wing for his club. The Free Wanderers took another 1-0 lead into the second half before YMCA responded with two goals. But where the Free Wanderers battled back with renewed energy, “the Young Men seemed fagged.” In the span of a few minutes the Wanderers scored three unanswered goals to finish 4-2 winners.[11] In the American Cup final at the Fall River Rovers Grounds on June 1, 1895, the Free Wanderers suffered a crushing 4-0 defeat to Kearny Caledonians. The era of Fall River/Pawtucket American Cup dominance was over.[12]

Another Watson on YMCA: “they being the first colored men to play the game”

When Pawtucket YMCA played Pawtucket Free Wanderers in a pre-season scrimmage on September 21, 1895, a Watson was listed at fullback.[13] In the season opener at home against the Fall River Olympics on September 28, two Watsons were listed, “F. Watson” at fullback, and “A. Watson” at center forward. Subsequent reports make it clear that “A. Watson” was Oliver “Allie” Watson: Oliver’s obituary and burial record show his name as Oliver H. A. Watson, or Oliver Henry Arnold Watson.[14] It appears he preferred to be known as Allie rather than Oliver, which was the name previous reports said he was registered under with the YMCA team. “F. Watson” was Oliver’s younger brother, Fred Watson. Reports of Fred Watson’s playing career actually preceded those of Oliver’s. In a junior league match between the YMCA Juniors and Providence Juniors on April 14, 1894, Fred broke the leg of the Providence captain, John Armstrong, when both simultaneously kicked the ball.[15]

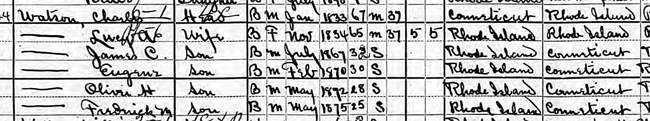

The Watson brothers were native New Englanders. Their father, Charles, was born in Connecticut in 1833, their mother Lucy (Curness) in Rhode Island in 1834. During the Civil War, Charles “was engaged in the maritime business” but for the bulk of his working life he was employed by E.P. Carpenter Co., a manufacturer of pipe organs.[16] A “devoted churchman,” Charles was also a founder of the Gaspee AME Zion Church in Providence; Lucy was eulogized as a “devoted member of the First Free Baptist Church.”[17] Oliver and Fred had three older brothers. Charles, born in 1864, worked as a machinist for the New York, New Haven and Hartford railroad; James, born in 1867, was a laborer and later a crew member on the steamer Orient.[18] Eugene, born 1870, was a musician, a newspaper reporter and editor who was also active in the local Republican party; on the same day in October 1895 the Pawtucket Evening Times highlighted Oliver and Fred in an analysis of the YMCA team, the newspaper reported Eugene had been elected secretary of the Colored Republican Club of Pawtucket.[19] Described as “somewhat of a leader among the negroes of this city,” he was active in the civil rights movement, sharing the stage at one meeting with Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells.[20] Oliver, born in 1872, became an “expert pressman and bolt maker.”[21] Fred, born in 1875, also worked in a bolt factory.[22] It is unclear how Oliver and Fred came to play soccer but Fall River and Pawtucket stand out in the early history of soccer in the United States as places where the sport was quickly embraced by native-born players and wasn’t viewed simply as the “English” or “Scotch” game.

Against the Olympics, a team made up of veteran Fall River players including six former ALPF professionals, the YMCA team had little hope and suffered a resounding 5-0 loss.[23] Said one report, “There were too many young and light players on the team to successfully combat a team of old experienced men as the Olympics lined up.” Fred, at the time 20 years old, was one of the few players on the YMCA team praised in match reports for his performance in the game. Allie, 23 years old and a winger being played out of position at center forward, “missed a great many chances for good passes and open kicks at goal.”[24]

The Watson brothers were both in the lineup again when YMCA played its next league match, a 2-2 draw in Pawtucket against the Free Wanderers on October 5. YMCA started the match shorthanded, with Fred one of just ten YMCA men on the field at kick-off. Allie was subbed in on the wing ten minutes after the opening whistle when it was learned a new forward “from one of the first-class teams in England” was ill and could not play. Despite his late appearance, Allie’s play, along with that of another new forward signing, was described as “first class” and the pair “passed and dribbled beautifully.” Allie still hadn’t found his goal-scoring form, however: three times he shot “a trifle high or wide…when it seemed as if the team must score.” Fred also played a part in the fightback as the team’s fortunes began to change when the young defender was moved from fullback to halfback.[25]

Newspapers in Fall River took note of the brothers’ play. YMCA’s first match of the season in the Spindle City was scheduled to take place on October 12 against the Fall River Rovers. The Daily Globe called the team “greatly strengthened” by the addition of the two “colored backs,” incorrectly reporting Allie’s position. The Fall River Daily Evening News commented, “The work of the two fast colored men recently added to the Y.M.C.A. will be matched [sic] with interest, they being the first colored men to play the game in this county.”[26] Only an unknown typesetter long lost to history can answer whether “county” was meant to be “country.”

In the event, neither Allie nor Fred appeared in the match, a 4-2 loss played in “a continual downpour.” The YMCAs were without several players who, one report said, were “doubtless expecting postponement.”[27] Another newspaper said players were missing because the team “had been obliged to leave Pawtucket at such an early hour to arrive in time for the game.”[28] Both brothers were in the lineup for an exhibition match the following week, a 2-1 win over Ashton Victors, with Fred among the players praised for their performance in the victory.[29]

A review of the YMCA team a few days later observed the team had the kind of “good material” that could make it “one of the best teams in the country” if “management uses good judgement in selecting the players.” The review noted, “Fred Watson is improving every game he plays,” while Allie would be more effective with “a little more life” in his play.[30] Allie must have taken the review to heart because when his team hosted Fall River East Ends on October 26, he found his goal-scoring form. With his team trailing 2-0 in the second half, Allie, “in the prettiest manner imaginable” bypassed the East Ends goalkeeper and “made the first goal for the local men.” By the time the final whistle blew Allie had tallied another goal in what finished as a 6-2 victory for YMCA.[31]

On November 9, 1895, YMCA met the Free Wanderers in the first round of the 1895-96 American Cup. Their places on the roster now firmly established, both Allie and Fred started for their team. After the kickoff, play moved back and forth between each goal with “astounding rapidity,” but neither team was able to score. Then a costly error from Fred showed his inexperience:

After being dangerously near each custodian the ball was finally forced in to the Y.M.C.A. territory, and despite the efforts of their backs it was soon so near the line that Fullback Watson, thinking it was over, picked it up for a goal kick, thus allowing their opponents a free kick from which they scored after a hot scrimmage.[32]

Undaunted, the YMCAs fought back, their supporters cheering “their men to an echo.” The team won a series of corners before Allie “tied the score on a well placed shot.” Now, the “excitement was at a fever beat” as each team fought for supremacy. In the second half, “the excitement became so intense that the usually boisterous supporters forgot to shout, so eagerly did they watch each play.” But with darkness falling, the score remained level at 1-1 when full time was called.[33]

The first-round replay was scheduled for November 28. Before that, YMCA fell 3-6 at home to Fall River Olympics in a New England League match. A Watson is listed at halfback for the loss but without a first initial; likely it was Fred at halfback given his appearance in the position on October 5.[34]

Fred played well in the American Cup first-round replay, where he “blocked many brilliant attempts at scoring.” YMCA fought back to equalize after the Free Wanderers opened the scoring, but the young team found itself down 3-1 at the half. YMCA clawed back another goal but never overcame the Free Wanderer’s goal advantage and at the final whistle the scoreline was 5-3. The YMCA’s American Cup dreams were over.[35]

Eliminated from the American Cup tournament, the YMCA team’s attention would’ve turned to improving their poor standing in the New England League. But available records show that, after the loss to Fall River Olympics on November 16, the team did not play another league match until March 1896. On December 18, 1895 it was announced that all New England League matches had been cancelled because of “severe weather,” with league play unlikely to resume until “sometime in March or April.” Instead, in the interest of minimizing travel expenses for the cash-strapped clubs, the only matches of consequence to be scheduled were Mayor’s Cup matches.[36] But, no records of Mayor’s Cup matches between the two Pawtucket sides have been located. YMCA and the Free Wanderers did meet in an exhibition game on December 21 and while Fred “did good work in keeping the ball away from the Y.M.C.A. cage,” his team lost 3-2.[37] A revised New England League schedule was announced on March 3, 1896, but Pawtucket YMCA did not return to play until March 28 when they lost 6-3 to the Free Wanderers.[38] On the same day, the league decided to cancel all the remaining games.[39] With the baseball season now underway, a newspaper report announced that all “interest in foot-ball at Pawtucket has ceased.” In order to “prevent running in debt,” the Free Wanderers and YMCA teams canceled all remaining matches, including those for the Mayor’s Cup.[40]

“The only two regular association players of their kind in the country”

Soccer struggled in Fall River and Pawtucket over the next few seasons. Interest in the game was so low the New England League did not meet to organize matches for the 1896-97 season. Another setback arrived like a hammer blow when the AFA organized the 1896-97 edition of the American Cup tournament without including Fall River and Pawtucket teams.[41] In 1897-98, a four-team Bristol County League was organized for Fall River sides with modest success. In Pawtucket, sporting attention was firmly focused on roller polo, a kind of hockey on roller skates played indoors away from the frigid New England winter. While occasional one-off soccer matches were played, the brief reports that can be found on the matches make no mention of the Watson brothers.

Finally, in the fall of 1898, Fred Watson appeared at full back with “a revised Pawtucket Free Wanderers” in a cold and rainy 4-1 win over Fall River Floats on October 29.[42] A preview for the match, originally scheduled for October 22, described the Free Wanderers back line as “about as strong as has been seen in this part of the country for many years.” The match report concluded, “Watson played a rare good game at full back. He saved pluckily, is very fast, and kicks with good judgement.”[43] Fred was “unable to play” when his team defeated Fall River C.C.’s 3-2 on November 7. Soon after, the New England League was “temporarily organized” with four teams: the Free Wanderers, C.C.’s, Floats, and the New Bedford Dartmouths.[44]

Fred appeared in the first league game of the season, a crushing 6-1 home loss to the C.C.’s played in “miserable weather conditions” on Thanksgiving Day.[45] He was not with the team when it defeated Floats 5-3 two days later. But the league did indeed prove to be temporary as early winter storms left heavy snow on playing grounds and high winds blew down the fencing surrounding enclosed grounds. The result was the postponement of New England League matches and the abandonment of the Bristol County League season. Before the end of December, the New England League suspended play until March. When March arrived, the league’s grounds were still in poor condition and the league again suspended play until the following season. In the meanwhile, exhibition matches were staged in Pawtucket.[46] Fred Watson was still included in the Free Wanderers’ player pool but did not appear in any of the exhibition games.[47]

The Watson brothers appear together again in a match report for the first time in four years on November 18, 1899. They lined up for Attleboro (Massachusetts) in a 0-1 home loss to Pawtucket North End in a friendly played at the Thatcher Grounds. Despite the loss, the match was the impetus for the formation of the “A.D.’s” team, or Attleboro and Dodgeville team. A week later both brothers were on the roster again when the A.D.’s defeated Pawtucket Rovers 7-1. Allie and Fred both appeared in two matches against Pawtucket North End during the 1899-1900 season, a 4-3 loss on December 30, 1899, and a 3-1 win on February 10, 1900.[48]

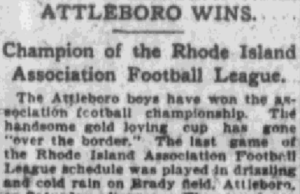

A new league, the Rhode Island Amateur League, was organized with seven teams for the 1900-1 season. Allie and Fred appeared together in nine matches for the A.D.’s, with each brother also appearing without the other one time. During the campaign, Allie tallied nine goals, a total that included two hat tricks. On April 20, 1901, the brothers were on the field for a 3-2 win over Pawtucket Rovers, a victory that gave the team the league championship, making Allie and Fred the first African American soccer players to be awarded championship medals.[49]

The Attleboro and Dodgeville team disbanded before the start of the 1901-02 season for reasons unknown.[50] By that time, the Watson brothers had moved to the Thornton squad, a picked team described in one report as “the pride of Pawtuxet valley.”[51] Fall River newspapers in previews ahead of an exhibition game on October 19, 1901 against the New Rovers prominently reported the presence of Black players on the team. One article in the Fall River Daily Globe noted, “They have playing with them two colored fellows who are said to be the only two regular association players of their kind in the country and they are crackerjacks at that.” Another Daily Globe report described the Thornton team as made up of the “best players to be procured in the state of Rhode Island” and wrote that, “The two colored players they have are the Watson brothers. One is a forward player and the other a full back.” The Fall River Daily Herald also commented, “The Thornton team has with it two colored players, who are spoken of as very good men.”[52]

Match reports also highlighted the race of the Watson brothers: “When the game was on, the spectators saw that the two Watson brothers (colored) were with the visitors.”[53] The brothers’ play was praised despite their team losing the match 5-3. The Daily Globe described Fred as “a good, strong mate” for his fellow fullback. Allie, “though not holding any long suit on scrimmages, showed the ability to pass very cleverly.”[54] While the Daily Globe noted Allie “failed to score on an excellent chance,” the Daily Herald described: “Watson is a colored man, as is the other Watson on the visiting team, and with his white companion played a beautiful passing game on their way down the field.”[55] The Fall River Daily Evening News had praise for Fred: “Watson, a colored player, did well at full, and his clever work won the favor of the spectators.”[56]

On October 26, the Thorntons played another exhibition game, this time winning decisively 5-1 against another Fall River team, the Acorns. The Daily Herald match report again praised the brothers’ play, saying Fred and his fullback partner “were a barrier the Acorns could not penetrate.” Allie and a fellow forward “showed they knew a thing or two about the game.”[57]

A few days before the win over the Acorns, the Pawtucket Evening Times reported the Thorntons had joined the Rhode Island Amateur League for the 1901-02 season but disputes revolving around the question of professionalism and accusations of ill-treatment by the league quickly led to the team’s departure.[58] Soon after, reports said the Thorntons would be joining the New England League, now reported as a professional league, only for the team to withdraw a week later and disband.[59] Former Thornton players moved to other league teams, and Fred joined Pawtucket Free Wanderers.

Professional: “very popular with fans”

The Free Wanderers opened the league season at home against Fall River Pocassets on November 9, 1901. With several starters unable to play, Fred lined up at halfback in the 4-2 loss. Fred was not on the roster for the 4-1 road loss to Fall River Oaks on November 16; the day before the match the Pawtucket Evening Times reported “16 regular professional players” had been signed by the team.[60] While the report does not name the professional players it is reasonable to conclude Fred was one of them, making him the first African-American professional soccer player to appear in a match in the United States.

Fred Watson’s play was praised in his next appearance, a 3-0 loss on November 23 to Fall River Pan Americans, so named because the team had won the soccer tournament at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo that September. The rough start to the season finally took a turn for the better on November 28, Thanksgiving Day, when the Free Wanderers defeated Fall River Oaks 5-1 at home.[61] Fred made several key defensive plays, including saving a goal. One report said Fred’s play “showed a decided improvement” and “was greatly admired,” adding, “Get in the game Fred.”[62]

Fred was at fullback for the 2-1 home win over Fall River Pocassets on November 30 and the 3-0 loss to the Pocassets in the return game in the snow on December 7. A Daily Globe report on the game in Fall River highlighted the performance of “the colored fullback” and his fellow defender, observing, “They certainly put up a great game and they had to.”[63] Appearances in a match in which the Pan Americans walked off the pitch after a disputed goal on December 14 and in a 2-1 home win over Fall River Oaks on December 21 followed.[64]

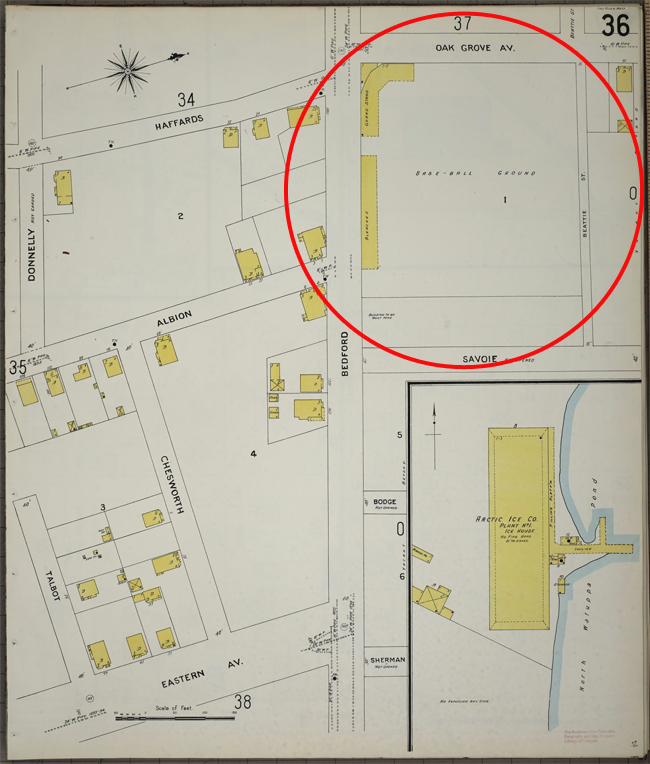

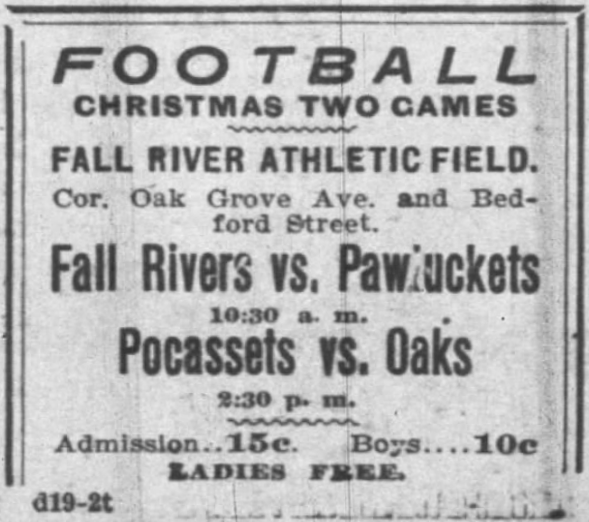

The Pan Americans hosted the Free Wanderers at the Fall River Athletic Field on Christmas Day 1901. Unaccountably for such an anticipated match, the Free Wanderers arrived with thirteen players, three of whom were unregistered. Rather than play an unregistered player, which would result in a forfeit regardless of the outcome, the Pawtucket team played the game with only ten men. Remarkably, the shorthanded side managed to prevent the Fall River team from scoring more than one goal at the end of the half. Even more remarkably, the Free Wanderers scored a goal of their own minutes after the start of the second half. Soon after that, Fred Watson was badly injured. The Daily Globe described,

Meikle sent the ball up the field in the air. Lynch went after it and so did Watson, the colored full-back. Lynch says the collision was almost inevitable and as he reached the ball he tried to jump to one side. While he was in the air Watson came up with a powerful kick. He kicked the ball but his foot caught Lynch squarely on the instep. Watson fell but Lynch seemed to go 10 feet in the air, turning a complete somersault and landed on the back of his neck. He got up somewhat dazed but Watson was helpless.[65]

His leg broken, the Fall River Daily Herald reported Watson “was taken in the arms of several players to the gate and across the street to a small store” to await the ambulance that had been summoned to take him to the hospital. There it was found he had “sustained a simple fracture of the right leg just below the knee,” although a later report said his injuries were “more serious than first thought” and that a bone in his ankle was also broken. The Fall River Daily Evening News noted Watson “was very popular with fans,” adding, “He was a strong kicker, and played a clean sportsmanlike game.”[66] The Pan Americans went on to win the game 6-1.

Several Pawtucket players remained in Fall River after the match and visited Fred in the hospital. The Daily Globe reported members of the Fall River and Pawtucket teams were arranging a benefit game for the injured fullback, “assisted by a number of local people who have volunteered contributions to help the cause along, as the colored fellow was one of the most popular players that ever came to this city.”[67] Updates on his recovery were reported in Pawtucket and Fall River papers over the next month. The same day the Pawtucket Evening Times reported he was home from the hospital, the paper informed readers that a date had been decided for a benefit match for “that well known player, Fred Watson.” Expectations in Fall River were that “the sale for the colored fellow will be quite a large one.”[68]

In the benefit match on January 25, 1902, the Free Wanderers lost 2-1 to the Pan Americans. But turnout for the match “for the popular colored full back” was strong, with “Fully 3000 people spectators” on hand.[69] Indeed, the large turnout became the impetus to form an association to fund the building of new enclosed grounds at the Free Wanderer’s Dexter Street Grounds. As the Pawtucket Evening Times explained,

Through the efforts of Watson’s friends, a large number of tickets were sold and the injured player was netted a handsome sum. It would have been larger had the field been enclosed by a fence, for quite a number came to the game without paying a cent. These same persons, all lovers of the game, would have cheerfully paid had they been obliged to, but as they were not Watson lost a tidy sum.[70]

A little more than a month later Pan Americans manager C.C. Murphy visited Fred in his home to give him his portion of the gate receipts.

Fred had just taken the plaster cast from his leg for good. He was much pleased to see Mr. Murphy, but when the latter turned him over a neat sum of money as the share of the benefit to which Fall River players and public contributed quite generously, the colored fellow could hardly find words to express his gratitude for the kind remembrance by the local followers of the game.[71]

While Fred was recovering, a Watson appeared for the Pawtucket Free Wanderers on the wing in three matches, scoring the lone goal in a 3-1 loss to the Pan Americans on February 1, 1902, but it is unclear if this was Allie. Beginning with the 1904-05 season, newspaper reports include a Watson at fullback on several different teams. But the reports do not include a first name or initial to aid in more precise identification. On March 18, 1905, four Watson’s were on the Pawtucket team roster in a Rhode Island State League match against Howard & Bullough, with an “A. Watson” at fullback and an “F. Watson” at left wing, flipping Allie and Fred’s familiar positions on the field. A commentary piece that mentions the match notes the large number of Watsons with the Pawtuckets but describes no familial connections.[72] In September 1906, Fred Watson is among the fullbacks included in the player pool of the Fairlawn team, although later match reports that include a Watson in the lineup do not provide a first name or initial.[73]

Conclusion

In many ways the story of the Watson brothers is unremarkable. Industrial workers in cities across the country took up soccer and competed in local and regional competitions. It was also fairly common for brothers and other family members to play together. What makes their story unique is that they were African American soccer players. At a time when major league baseball began to enforce a color line, the sport of soccer displayed a willingness to accept Black players as equals. Despite their participation, the specter of racism could at times rear its ugly head. At least one early newspaper story contained elements of racial caricature and we may never know if, or to what extent, Allie and Fred experienced racist abuse on the field. Nevertheless, it is clear from multiple positive press reports and the outpouring of support when Fred broke his leg that the brothers were accepted and respected, not only as athletes but also as men.

Even as the Watsons hung up their cleats, reports from other cities show that more and more people of color were taking up the sport. The first documented Black soccer organization in New York City formed in 1908 and was called the Spartan Club. A year later the champion Barrow School boys soccer team of Springfield, Massachusetts, included three African American boys in the squad.[74] Although progress over the next decade was slow, the 1920s and 1930s saw a boom in the number of Black clubs forming in New York. Many of these sides competed against White teams in various local competitions including the Empire State League and the Metropolitan League. Even historically Black colleges such as Hampton Institute and Howard University tried out the sport. Eventually, pro players of African descent such as Tewfik Abdallah and Joe Gaetjens competed in the American Soccer League and on the international stage. Gil Heron, who is often thought of as the first Black professional soccer player in the United States, made his debut in 1946.[75] The story of the Watson brothers is an opportunity to expand the timeline of Black participation in soccer and enables us to reconsider the role of people of color in US soccer history.

By 1907, the Watson brothers seem to have stopped playing soccer for good and we find no evidence they appeared in any more organized games. As they faded from public view, they continued to live their lives, perhaps unaware of their role as pioneers. Oliver passed away at the age of 53 in May 1925, unmarried, and survived only by his brothers Fred and Eugene. Fred married Elsie L. (Levina) Watts in May 1901, who passed away in March 1931. Like his older brothers, Fred and Elsie had no children. Fred was 66 years old when he died in December 1941.

Watson Brothers Appearances by Club*

Oliver H. A. “Allie” Watson (27 appearances, 15 goals)

| Season | Competition |

Club |

Appearances | Goals |

| 1894-95 | New England League | Pawtucket YMCA | 1 | 1 |

| 1894-95 | American Cup | Pawtucket YMCA | 3 | 2 |

| 1894-95 | Exhibition | Pawtucket YMCA | 1 | 0 |

| 1895-96 | New England League | Pawtucket YMCA | 3 | 2 |

| 1895-96 | American Cup | Pawtucket YMCA | 1 | 1 |

| 1895-96 | Exhibition | Pawtucket YMCA | 1 | 0 |

| 1899 | Exhibition | Attleboro | 1 | 0 |

| 1899-1900 | Rhode Island Amateur League | Attleboro and Dodgeville | 3 | 0 |

| 1900-01 | Rhode Island Amateur League | Attleboro and Dodgeville | 10 | 9 |

| 1901 | Exhibition | Thornton | 2 | 0 |

| 1904-05 | Rhode Island League | Pawtuckets | 1 | 0 |

Fred Marcus Watson (37 appearances)

| Season | Competition |

Club |

Appearances | Goals |

| 1895-96 | New England League | Pawtucket YMCA | 4 | 0 |

| 1895-96 | American Cup | Pawtucket YMCA | 2 | 0 |

| 1895-96 | Exhibition | Pawtucket YMCA | 3 | 0 |

| 1898-99 | New England League | Pawtucket Free Wanderers | 2 | 0 |

| 1899 | Exhibition | Attleboro | 1 | 0 |

| 1899-1900 | Rhode Island Amateur League | Attleboro and Dodgeville | 3 | 0 |

| 1900-01 | Rhode Island Amateur League | Attleboro and Dodgeville | 10 | 0 |

| 1901 | Exhibition | Thornton | 2 | 0 |

| 1901-02 | New England League | Pawtucket Free Wanderers | 8 | 0 |

| 1904-05 | Rhode Island League | Pawtuckets | 1 | 0 |

| 1906-07 | Rhode Island League | Fairlawn Independents | 1 | 0 |

*Appearances and goal totals are representative of the best currently available evidence from contemporary newspaper reports and are likely incomplete.

Endnotes

[1] “Injured at Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 16, 1894, 6; “Variety of Sporting,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 26, 1894, 7.

[2] For more on the soccer scene in Fall River at this time see Ed Farnsworth, “After the collapse: ALPF vs. ALPF in Baltimore and Fall River, 1894-96,” Society for American Soccer History. Last modified April 27, 2020 https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/after-the-collapse-alpf-vs-alpf-in-baltimore-and-fall-river-1894-96/.

[3] “Variety of Sporting,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 26, 1894, 7.

[4] “On the Wane,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 24, 1894, 1; “Walkover for the Olympics,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 24, 1894, 7.

[5] “On the Wane,” 1.

[6] “Rovers Defeated,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 29, 1894, 7.

[7] “Association Football,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Jan. 21, 1895, 8: “Football Passes,” Fall River Daily Evening News,” Feb. 4, 1895, 4.

[8] “East Ends Exit,” Fall River Daily Globe, Mar. 11, 1895, 1.

[9] “Y.M.C.A. Defeats East Ends,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Mar. 11, 1895, 2.

[10] “Exciting Contest,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Apr. 22, 1895, 2.

[11] “The Wanderers Won,” Pawtucket Evening Times, May 6, 1895, 7.

[12] “Hot Kicking,” Fall River Daily Globe, Jun. 3, 1895, 1; “Cup Goes West,” Fall River Daily Herald, June 3, 1895, 7.

[13] “The Game in Pawtucket,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 23. 1895, 7.

[14] “Mortuary,” Pawtucket Times, May 26, 1925, 9; Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission, Walnut Hill Cemetery, (http://rihistoriccemeteries.org/newgravedetails.aspx?ID=192059), entry for Oliver H. A. Watson.

[15] “Injured at Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 16, 1894, 6.

[16] “Charles Watson Dead,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 15, 1915, 16.

[17] “Mortuary,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 17, 1915, 3; “Mortuary,” Pawtucket Evening Times, May. 9, 1905, 9.

[18] Charles F. Watson, 1910 U.S. Census, Kent County, Rhode Island, population schedule, Ward X, East Greenwich town, sheet 23 A, dwelling 425, family 558; “Mortuary,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 17, 1915, 3; “Mortuary,” Pawtucket Evening Times, April 26, 1909, 10.

[19] “Watson, Eugene Alexander,” in Who’s Who of the Colored Race: A General Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of African Descent, Volume One 1915, ed. Frank Lincoln Mather (Chicago: Frank Lincoln Mather, 1915), 278; “Two Colored Republican Clubs,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 24, 1895, 6.

[20] “Which is the “Truly’ Orator,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 3, 1899, 6; “Told in Paragraphs,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 30, 1894, 8.

[21] “Mortuary,” Pawtucket Times, May 26, 1925, 9.

[22] Frederick M. Watson, 1900 U.S. Census, Providence County, Rhode Island, population schedule, 2nd Ward, City of Pawtucket, sheet 15, dwelling 222, family 344; Frederick M. Watson, 1910 U.S. Census, Providence County, Rhode Island, population schedule, X Ward, Sheet 20, dwelling 281, family 371.

[23] “One for Olympics,” Fall River Daily Herald, Sep. 30, 1895, 7.

[24] “Y.M.C.A. Defeated,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Sep. 30, 1895, 2.

[25] “Played a Tie Game” Pawtucket Evening Times. Oct. 7, 1895, 2. While the Evening Times report repeatedly refers to Allie’s play, the Fall River Daily Globe’s report lists him in the lineup as “O. Watson.” “Tie Game,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 7, 1895, 1.

[26] “Football Notes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 11, 1895, 8; “Football Passes,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Oct. 11, 1895, 7.

[27] “Rovers Win,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 14, 1895, 1.

[28] “Local Elevens Win,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 14, 1895, 7.

[29] “Y.M.C.A. Team Practice,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 21, 1895, 2.

[30] “Foot Ball Notes,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 27, 1895, 2.

[31] “East Ends Beaten, “Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 28, 1895, 2.

[32] “Association Football,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 11, 1895, 2.

[33] “Association Football,” 2.

[34] “The Olympics Won,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 18, 1895, 2.

[35] “Free Wanderers Won,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 29, 1895, 4.

[36] “Football Games,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 18, 1895, 1.

[37] “An Exhibition Game,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 23, 1895, 2. YMCA hosted and lost 3-2 to Fall River Rovers in a Christmas Day exhibition game but no roster is available for the game. “Rovers Defeated Y.M.C.A.,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 26, 1895, 2.

[38] “Wanderers Won,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Mar. 30, 1896, 2.

[39] “Out for the Cup,” Fall River Daily Herald, March 31, 1896, 7.

[40] “City Briefs,” Fall River Daily Herald, Apr. 22,1896, 7.

[41] “No Football Games,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 10, 1896, 6; “Frozen Out,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 27, 1896, 8.

[42] “The C.C.’s Defeated,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 7, 1898, 7.

[43] “Pawtucket Team Made an Excellent Showing Against Fall River Floats,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 31, 1898, 2; “Saturday’s Game,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 20, 1898, 2.

[44] “The Pawtuckets Defeated the Strong C.C’s After a Pretty Exhibition,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 7, 1898, 2; “Temporary Organization,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 21, 1898, 8.

[45] “Pawtucket Defeated,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 25, 1898, 2.

[46] “Weather a Detriment,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 2, 1898, 4; “N. E. Football League,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 21, 1898, 8: “Association Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Mar. 27, 1899, 4.

[47] “Association Foot Ball,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Apr. 19, 1899, 2.

[48] “Rovers Were Badly Beaten,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 27, 1899, 2; “North End Victorious,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 1, 1900, 2; “Honors Even,” Pawtucket Evening Times, February 12, 1900, 9.

[49] “Game Schedule,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 10, 1900, 2; “Darkness Interfered,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 26, 1900, 2; “Association Football,” Pawtucket Evening Bulletin, Nov. 30, 1900, 2; “Amateur Football,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 30, 1900, 2; “Attleboro 7, Atherton 0,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 3, 1900, 2; “League Football,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 17, 1900, 2; “Attleboro Still Leading,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 24, 1900, 2; “Called a Draw,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 31, 1900, 2; “Amateur League Football Games,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 7, 1901, 2; “No Goals Gained,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 28, 1901, 2; “Schedule Off,” Pawtucket Evening Times, April 1, 1901, 9; “Manville Beats Attleboro Team,” Pawtucket Evening Times, April 15, 1901, 2; “Attleboro Wins,” Pawtucket Evening Times, April 22, 1901, 9.

[50] Association Football League,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 17, 1901, 2.

[51] “East End Echoes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 16, 1901, 7.

[52] “East End Echoes,” Oct. 16, 1901, 7; “East End Echoes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 18, 1901, 7; “Tomorrow’s Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 18, 1901, 2.

[53] “Five to Three,” Fall River Daily Globe, Oct. 21, 1901, 7.

[54] “Five to Three,” 7.

[55] “Rovers-Thornton,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 21, 1901, 6.

[56] “Rovers Win,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Oct. 21, 1901, 7. Inexplicably, Oliver is identified in the Fall River newspaper reports with the first initial “J,” with the Daily Globe referring to him as “Jim.” No reports have been found to suggest the oldest Watson brother, James, who was 34 years old at the time, played soccer. The same report reverses the ages of Oliver, then 29, and his younger brother Fred, who was 26. Reports on the brothers’ next match together use the correct initials.

[57] “Acorns defeated,” Fall River Daily Herald, Oct. 28, 1901, 6.

[58] “Association Football League,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 15, 1901, 9; “Association Football League,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Oct. 17, 1901, 2.

[59] “New Football League,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 1, 1901, 1; “New England Football League,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 7, 1901, 7; “New Football League,” Fall River Daily Globe, Nov. 7, 1901, 1. “League to Meet,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 15, 1901, 2.

[60] “On Association Football Fields,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 11, 1901, 2; “The Oaks Won,” Fall River Daily Herald, Nov. 18, 1901, 6; “League to Meet,” 2.

[61] “With the Association Teams,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 25, 1901, 2; “Association Football, Pawtucket Evening Bulletin, Nov. 29, 1901, 2.

[62] “Football Results Association Game,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 29, 1901, 2; “Goal Kicks,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Nov. 29, 1901, 4.

[63] “Pawtuckets Play Great Game,” Pawtucket Evening Bulletin, Dec. 2, 1901, 2; “Pocassets Won,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 9, 1901, 7.

[64] “Forfeited the Game,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 16, 1901, 6; Another Protest,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 16, 1901, 1; “Pawtuckets Defeat Oaks of Fall River,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Dec. 23, 1901, 2.

[65] “Over Four Thousand Persons,” Fall River Daily Globe, Dec. 26, 1901, 1.

[66] “Christmas Football,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 26, 1901, 6; “Flint Village,” Fall River Daily Herald, Dec. 30, 1901, 5; “Fall River 6, Pawtucket 1,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Dec. 26, 1901, 5.

[67] East End Echoes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Jan. 30, 1902, 8.

[68] “Fred Watson Improving,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 2, 1902, 2; “Fred Watson Home,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 16, 1902, 2; “Ned Birt Chosen Captain,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 16, 1902, 2: “Globe Gossip,” Fall River Daily Globe, Jan. 18, 1902, 1: “East End Echoes, Fall River Daily Globe, Jan. 21, 1902, 7.

[69] “Pan Americans 2, Free Wanderers 1,” Fall River Daily Evening News, Jan. 27, 1902, 5; “Pans Won the Game,” Fall River Daily Herald, Jan. 27, 1902, 6.

[70] “Athletics Field Contemplated,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Jan. 28, 1902, 2.

[71] “East End Echoes,” Fall River Daily Globe, Mar. 13, 1902, 7.

[72] “Holburn Injured, Pawtucket Lost,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Mar. 20, 1905, 2; “Punts,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Mar. 20, 1905, 2.

[73] “Fairlawn,” Pawtucket Evening Times, Sep. 7, 1906, 12.

[74] Brian D. Bunk, “The Barrow School Socker Football Team,” Society for American Soccer History. Last modified Feb. 13, 2020, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/the-barrow-school-socker-foot-ball-team/.

[75] Brian D. Bunk, “Gill Heron,” Society for American Soccer History. Last modified Feb. 4, 2020, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/gil-heron/; Brian D. Bunk, “What Kind of Player was Gil Heron?” Society for American Soccer History. Last Modified Feb. 6, 2020, https://www.ussoccerhistory.org/what-kind-of-player-was-gil-heron/.

Pingback: Black History Month: The Watsons of AmericFootball - Theultramods

Pingback: Gil Heron – Society for American Soccer History