It began in a smoke-filled club room as the boys gathered with drinks in hand. It started amid the fiery glow of the blast furnace or the inky dark of the mine. The men told stories about their childhood games and longed for a chance to once again run and kick and push. Perhaps they had a go at soccer during a festival or holiday celebration and decided they would enjoy playing more often than once or twice a year. For others, it was a return to a profession they had had back home when they trod the sward at Tontine Park. Wherever it happened, and whatever the reason, the men decided they wanted to form a soccer club. First though, they had to find enough willing players. If it was based on a social club, recruitment was relatively straightforward as they could call upon the members. If it emerged from the factory floor, they might ask around during breaks or the slow walk home. Many relied on family to fill out a squad or tapped folks they knew from the cities and villages where they had once lived back in the old country. At times, they placed ads in newspapers asking interested parties to gather at a hotel or clubhouse on a certain date.

Once they had enough brave souls willing to take the leap, they set about organizing. Formal clubs needed officers and elections soon produced a president and vice president, a treasurer, and a secretary. Sometimes, especially if the men worked at the same place, they named an honorary president who inevitably held a position of authority in the firm. Running a club is expensive and the squad needed resources – money to pay for equipment and kit, transportation to away games, and a place to play. A well-connected patron could recruit talented players by offering them both a position on the pitch and on the assembly line. Eager employers believed that paying for jerseys and building a ground might distract the workers from agitating for higher wages and shorter hours. Once the coffers were full they sought out the necessary equipment: balls, goals, boots, and uniforms. Such items might already be at hand in a local sporting goods shop or they could buy them through a catalog, perhaps the one put out by the famous Spalding company. In some cases, they ordered them from overseas and waited impatiently for the ship to come in from Glasgow or Liverpool.

It was time to play some games. Days before a match, the club secretary posted a notice in the local paper or mailed out postcards to the players with the expectation that all would be ready to go. Those who were no-shows faced fines or other penalties. Often the manager was responsible for arranging transportation to away matches and the players usually traveled together. Depending on the distance, they might take the train, although complex schedules and different time zones led to late arrivals and forfeits. For closer visits, they might take a horse car, trolley, or even walk. On game day the home team paid for all expenses. The layout included flyers to advertise the match, rent for the ground, and payments for the referee and security. Keeping the peace was often a tall order given the fact that many fields were unfenced and fans packed together along the edges of the pitch, just a few feet from the action. Tensions between supporters and between players meant that fisticuffs were not uncommon. A particularly rowdy crowd could storm the pitch, easily overwhelming the police officers, causing delays and sometimes cancellations. Teams played on empty, undeveloped lots or rented the grounds from other athletic organizations, especially baseball teams. They may have played on fields provided by a generous employer. Supporters placed wagers on their favorite team and clubs laid down their own stakes.

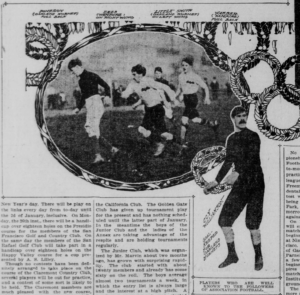

The local press covered the action, sometimes writing long pieces analyzing team tactics and the skill (or lack thereof) of individual players. Rarely a photographer might be on hand to capture some of the action. If no reporter was present at the match, the teams or the league sent results and updated standings to the newspaper. Arranging a match with a squad from a distant city was more complicated. Once again club secretaries did much of the heavy lifting. They communicated with potential rivals, negotiated guarantees, and arranged for transportation. The secretary may even have helped determine how much money the winning side took home and what prize, usually silver or gold medals, was given to the players. For the home side, these matches were seen as money-spinners, yet another way to provide revenue for the club. Such arrangements were not without risk however, poor weather or an indifferent crowd could lead to serious financial loss. Victory over a well-known side from a rival city earned bragging rights and perhaps an inflated claim to some hypothetical regional or national title.

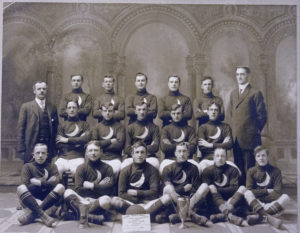

Once the final whistle blew the teams ate and drank together at a banquet or smoker. Such events could be informal gatherings or large-scale affairs designed to toast a visiting squad or to celebrate an end-of-season championship. Depending on the result, a protest might be lodged. Teams complained about a lot of things from sub-par field conditions, to ineligible players and bad refereeing decisions. These disputes, along with the violence on the pitch, generated bad blood and bad publicity. The rancor caused league officials to resign and teams to withdraw from competition. Title-winning sides sometimes had their picture taken on the field immediately after their moment of triumph. Later, they donned their kit, assembled for a formal portrait in a photographer’s studio, and proudly posed with their trophies. The club distributed these images to its members and once real photo postcards became more common, they found their way into the hands of supporters. The souvenirs, often lovingly annotated with names and scores, became treasured mementos of a successful season. After a summer respite, they would reconvene in the fall to begin the whole process over again.