Doing American soccer history can be hard, but doing African American soccer history is harder still.

Too often there is an uncooperative historical record, so historians have to look long and hard to unearth even the tiniest of leads—a two or three sentence match report, a sepia-toned photograph, or some bit of oral history. From there, with some diligence and luck, a story can unfold, even if it is an incomplete one.

Importantly, the number of African American soccer stories has increased recently, notably with a string of Black History Month posts at Stars and Stripes FC by Donald Wine II, and the recent scholarship of historian Dr. Jermaine Scott, who writes on the African American soccer experience.

Dr. Brian Bunk, a professor of history at University of Massachusetts-Amherst, documented in several recent posts on the Society website that stories of African American participation in soccer, especially during the first half of the twentieth century, still remain “largely unknown and untold.” He then ably goes on to tell stories of pioneer Gil Heron and the integrated schoolboy team of the Barrow School team of Springfield, Massachusetts.

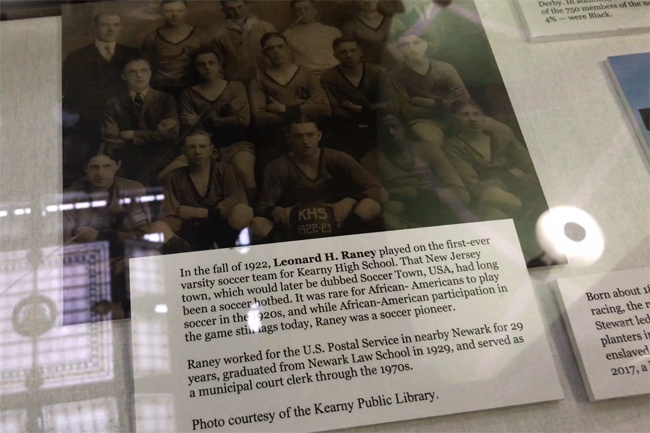

I stumbled on one such “unknown and untold” story at the Kearny Museum, a lead that came from a photograph of the first varsity soccer team at New Jersey’s Kearny High School in 1922-23. Tucked in the back of a museum display case, the nearly 100-year-old picture revealed a young African American man. Seated, with his arms and legs crossed, Leonard Raney stared at the camera. Born in Kearny in 1905, Leonard Raney’s parents came to town from Virginia as early participants in the Great Migration. Leonard’s father was a laborer and his mother was a housekeeper. Later, Mrs. Raney helped run a boarding house. The Raney presence in Kearny was an anomaly as there were few African Americans living on the east side of the Passaic River. A much larger and ever-growing black community lay just across the river in Newark.

But the fact that Leonard played soccer was no mystery at all. He lived at the base of Cooper’s Block, a working-class neighborhood where many Scottish and Irish immigrants lived. Some of the greats of the game had been nurtured within its confines, including Archie Stark, Jim Ford, Davey Brown, Jimmy Douglas, every one a future U.S. international.

The local kids played pick-up soccer on empty lots and joined junior teams. Beginning in the 1920s, the best the town could produce played for the high school team, and Leonard Raney was one of them. Surely, he learned the game in one of the cradles of American soccer alongside his neighbors and classmates. Yet, there is so little that documents his soccer career. There is an odd mention in the local newspaper and an interview of Leonard as an older man from a local television station (he appears at 0:20). He was not too fond of the “modern game.”

That picture, the interview, the brief mention in a faded newspaper clipping asked more questions than they answered. What were Leonard’s life experiences? His soccer stories? Raney’s obituary provided a few answers. He worked for the United States Postal Service for several decades and put himself through law school before serving as a Newark city clerk for nearly twenty years. He died at 96.

I tried to find relatives via Facebook without success (not everyone uses Messenger) before seeking information the old fashioned way, fittingly through a letter to his daughter. I have not heard back yet.

In the meantime, Leonard Raney’s unknown and untold and incomplete story is part of a current exhibit at the Newark Public Library. Dale Colston, the curator of “The Black Athlete in America: Protest, Activism and Inclusion,” included the early twentieth-century soccer pioneer in one of the exhibit’s display cases with the team photograph and a pair of vintage soccer boots. The display included the following caption:

In the fall of 1922, Leonard H. Raney played on the first-ever varsity soccer team for Kearny High School. That New Jersey town, which would later be dubbed Soccer Town, USA, had long been a soccer hotbed. It was rare for African Americans to play soccer in the 1920s, and while African-American participation in the game still lags today, Raney was a soccer pioneer.

Raney worked for the U.S. Postal Service in nearby Newark for 29 years, graduated from Newark Law School in 1929, and served as a municipal court clerk through the 1970s.

There is more to learn and there is hope that something comes back from Raney’s long-time employer—the U.S. Postal Service.