This post is the first of a two-part series telling the story of two soccer-playing soldiers who served during World War I. Thanks in part to family members Clyde Behrendt and Andrew Smith who reached out to me, I have more detail about the lives of Joe Cunat who played on the US team at the Inter-Allied Games in 1919 and James Currie who lined up for Bethlehem Steel in 1922.

Joseph Cunat was born in Braidwood Illinois on March 13, 1895. His parents came from what was then called Bohemia and would later be known as Czechoslovakia. They arrived separately in the United States in the 1870s and were married in 1890. As native Czech speakers, the family name was originally pronounced “Chyu-nut” but like so many immigrant family names it was later changed to “Cue-gnat.” Joe had two sisters and an older brother. Coal had been discovered in Braidwood in 1864 and like many immigrant men, Joe’s dad worked in the mines.

James Currie’s father was also a coal miner but in Scotland, not Illinois. James himself was born on Valentine’s Day 1896 in Galston, a town of about 5,000 people four miles east of Kilmarnock. Not much is known much about his childhood but he had two brothers and two sisters although one died in infancy. It’s likely he had always played soccer, first with his brothers and eventually for local teams Prestwick and Glenleven Rovers.

Joe spent his childhood in typical boyhood pursuits: hunting mushrooms, swimming, fishing, camping and roughhousing with friends. By the time he was in his early twenties, he had relocated to Chicago to work as a printer. The Midwestern metropolis was a mixture of various ethnic groups and Czechs like Cunat and his friends settled in neighborhoods like Pilsen, South Lawndale, Cicero, and Berwyn. Many of these pals joined Joe in playing for the Rangers Athletic Club baseball team.

Although his father labored in the mines, James worked as an apprentice coach maker for the North British Railway Company before joining the army in 1913. When World War I broke out in August 1914 Currie’s unit the 2/Scottish Rifles was in Malta. They quickly returned to England before shipping out to France, landing at La Havre on November 5. The 2/Scottish Rifles spent the last few months of 1914 alternating between reserve duty and service at the front lines, manning trenches in the region along France’s border with Belgium. Although the battalion did not participate in any major military actions that year they still came under fire, losing a handful of men each week to German bullets and artillery shells.

The rhythm of action – three or four days in the trenches followed by a similar period behind the lines – continued through the first two months of 1915. The routine changed at 8:30 a.m. on the morning of March 10, when two companies of the 2/Scottish Rifles went over the top, rushing across icy fields to attack enemy lines at Nueve Chappelle.

One company advanced quickly but the other faced heavy fire and men fell at an alarming rate. Part of the problem was that an artillery unit tasked with shelling the German positions had been delayed and was unable to neutralize the enemy’s machine guns. The results were deadly for the battalion and within an hour most of its officers had been killed or wounded. In his 1967 book about the Scottish Rifles at Nueve Chappelle titled Morale, John Baynes settled on a total casualty figure of 469 or one man for every yard captured.

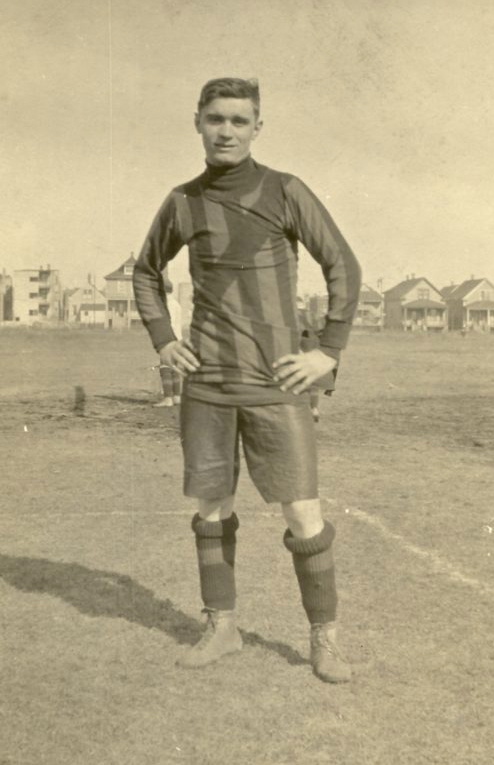

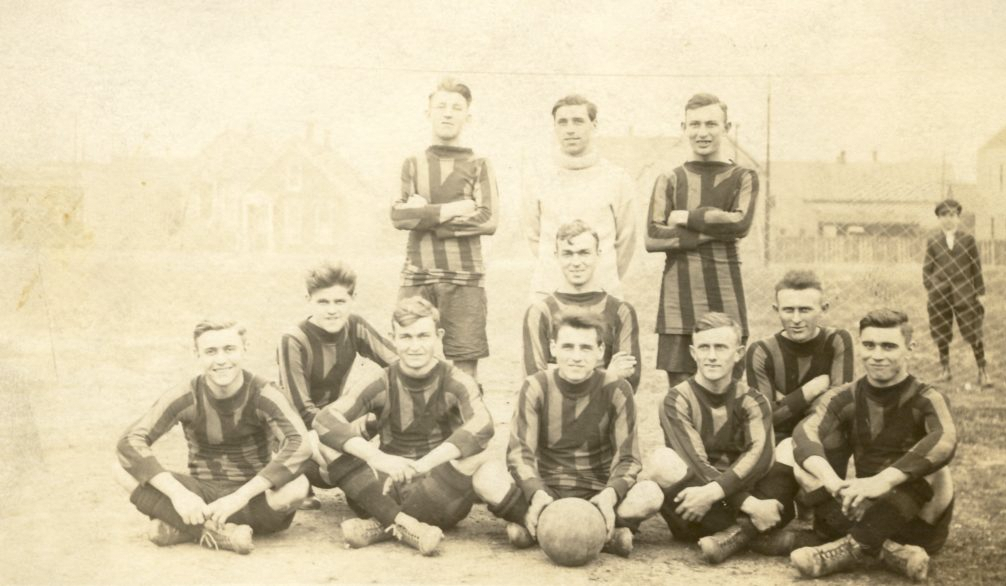

While Currie was manning the trenches in France Joe continued his life in Chicago. By the time the war started soccer was booming in the Czech neighborhoods and Joe lined up for clubs such as the Hungarian-Bohemians and the American-Bohemian club. Within a few years, a number of other teams sprouted up including Atlas, Olympia, Union, and Sparta. Participating in these activities helped connect second-generation immigrants like Joe to older, mostly foreign-born members of the community. Negative attitudes toward Czechs from some corners of the city led to tensions and these conflicts sometimes played out on the soccer pitch. After a series of controversial decisions and even some on-field violence most of the Czech teams decided to organize themselves as the fourth division of the Chicago District Soccer League. Joe’s team the Rangers claimed the John A. Gouger Cup as division winners. Although playing in the fourth division the club clearly had some talent as they managed to score 100 goals while conceding just one, and even that one was an own goal.

For men like James who survived Nueve Chappelle life once again settled into the by now familiar pattern of trench duty and rest, although even when the soldiers were behind the front lines they often worked on projects like building latrines or burying the dead. They also played sports. Competitions between units – from the platoon to the division level – became important ways of building morale and lightening the burden of war. As the conflict dragged on, men stationed behind the lines often trained during the morning and played games in the afternoon. When Currie joined the 2/Scottish Rifles he may have learned about the unit’s proud history playing soccer. Such information was often communicated to newcomers and helped build a sense of esprit de corps.

The 2/Scottish Rifles team was generally quite good although they had declined the offer of a Christmas truce in 1914 when other units paused hostilities to compete at football with the enemy. The first sign of the battalion’s prowess on the pitch came on May 5, 1916 when the Brigadier was on hand to present the Brigade Football Cup to the regiment and bestow medals on some of the team’s players. Eight days later the side defeated the 8/York and Lancaster regiment 4-0, booking their place in the Division Football Cup Final. The match was played on May 23 and with their commanders looking on the team captured the trophy with a 3-1 win over 8/Divisional Cyclists.

During the summer of 1916 Currie’s unit once again rotated between rear areas and the front lines, spending much of the time out of combat. Nevertheless, while in their trenches they continuously faced the threat of enemy soldiers stationed on average only 200-300 yards away. In early July the unit took part in combat near La Boiselle and a few months later on October 23, 1916 the battalion assaulted a German position called Zenith trench as part of the larger operation known as the Battle of the Somme. With over 240 killed or wounded it was the bloodiest action the unit had seen since Nueve Chappelle. The unit’s War Diary proudly noted “the advance was carried out with the utmost gallantry and determination by all ranks under heavy artillery and m.g. fire.” The battle also featured numerous acts of individual bravery including 2nd Lieutenant J. Ferguson who destroyed three machine-gun positions before he was killed.

James also performed heroically during the war and earned a Military Medal in November 1916. Established that year the M.M. was given to infantrymen for acts of bravery in battle on land. The award may have been given for gallantry during the fighting near La Boiselle since notification generally came three to four months after the actions that merited the award. After the Somme the men remained billeted behind the lines but found time to trounce the Cameronians 5-0 on November 30. A Christmas Day football match between sergeants and officers ended in a 2-1 victory for the former.

As war raged in Europe normal life continued for Joe Cunat back in Illinois as he worked as a printmaker and continued playing soccer. In the 1917-18 season, his Rangers squad completed a local double winning both the Chicago league’s third division crown with a 12-1-1 record while also capturing the third division cup. The squad also reached the semi-final of the Peel Challenge Cup, Illinois’s most prestigious cup competition. After losing a closely contested match to the Bricklayers and Masons 2-1 it was reported that all 15 members of Rangers enlisted. Eventually, Joe reported for training to Camp Grant at Rockford Illinois. Officially Joe was a Sergeant with Company E, 343rd infantry regiment, 172nd infantry brigade, 86th infantry division – also called the Blackhawk Division. Even while stationed in Rockford, he continued to turn out for various camp teams as well as for his Rangers.

A version of this essay first appeared at www.SoccerHistoryUSA.org on November 11, 2017.

Pingback: James and Joe, part 2 – Society for American Soccer History