This is the second of two posts detailing the lives of two soccer-playing soldiers: Joe Cunat and James Currie. The first part can be read here.

James Currie spent early 1917 much the same way as previous months – rotating in and out of the trenches. In April, his unit participated in various combat operations before spending half of May training in new forms of trench-to-trench attacks. During the first three weeks of July the soldiers underwent still another period of intense training in preparation for a major operation planned for the end of the month.

Known as the Battle of Passchendaele the 2/Scottish Rifles attacked at a place referred to in the War Diary as Mud Lane. The results of the fighting for James’s unit were 38 men killed, 146 wounded and 19 missing. After a week of rest the unit made another advance at Bellewaarde Ridge leaving 29 killed, 13 wounded and 6 missing. It was probably for his actions during one of these engagements that James earned the Distinguished Conduct Medal. The London Gazette stated the award was:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. During an attack, when his platoon was held up by a hostile machine gun which was inflicting many casualties, he advanced by himself and killed the three men who composed the gun team single-handed, thus enabling his platoon to advance to their objective.

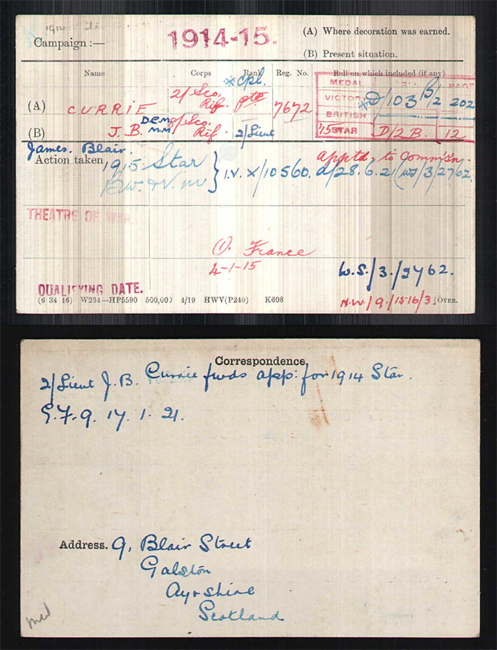

The battalion experienced a fairly quiet autumn and spent most of December resting and training. The football team captured another title, winning the Divisional Football cup on December 23. The announcement of Currie’s D.C.M. in the Gazette indicated that he had now risen to the rank of Lance Sergeant. At some point in 1918 he entered officer training and on May 1 was named a temporary 2nd Lieutenant.

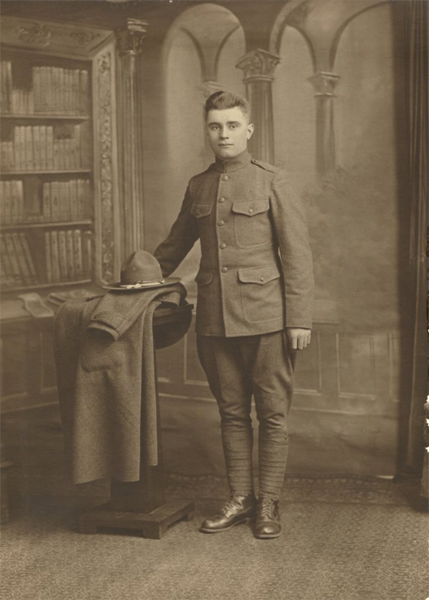

About four months later on September 8, 1918 Joe Cunat set sail for England. The trip was uneventful if not particularly comfortable because only some of the ships had bunks installed while others contained simple hammocks. All of them were so tightly packed that at times it became hard to breath. Joe’s berth was likely on the Walmer Castle, a British passenger ship originally launched in 1902. After landing they were immediately confronted with English autumn weather – drenching rain – along with long marches through mud choked lanes. A number of men died due to the Spanish flu. After crossing the channel at night the Americans landed at La Havre, France before continuing on by rail to the Medoc region. Joe’s unit was billeted at Saint Loubès a few miles northwest of Bordeaux. It’s likely that Joe was one of the non-commissioned officers sent to “finishing schools” and not one of the 9,000 enlisted men transferred to other units as replacements. By November 8 the unit was ordered to Le Mans where they would be prepared for combat. The signing of the Armistice on November 12 canceled these plans and the next day the Blackhawk Division was broken up. Joe remained in France and was assigned to assist at the American Expeditionary Force Departure Center, duty that some disparaged as being akin to hotel-keeper.

Through it all Joe kept playing soccer. In May 1919, he played on the Le Mans team that captured the American Expeditionary Force championship. In the first match they defeated Intermediate Section 5-2 and followed that up with a 10-1 trouncing of General headquarters. Two days later they captured the title in a marathon match over Third Army, winning 3-1 after 180 minutes of play. Joe played a crucial role in defense and his work as right half back helped keep Third Army from scoring more than a single goal. In June, Joe was chosen to represent his country at the Inter-Allied Games in Paris. Although the US team beat Canada 5-4 they could not compete with the stronger European sides losing 7-0 to Belgium and 8-2 to eventual tournament winners Czechoslovakia.

After finishing the war as a 2nd Lieutenant and leaving the army James Currie embarked on a career as a professional footballer. He originally signed with Kilmarnock but moved to Notts County without making a first-team appearance for the Scottish side. He lined up for the Magpies in the English First Division during the 1919-20 season making his debut on September 6 in a 1-2 home loss to Burnley. On September 27, 1919 he scored the opening goal after 18 minutes versus Manchester City. Twenty-two thousand fans packed Hyde Road on a beautiful fall day to see the home side claim a 4-1 victory. It is hard to imagine how James must have felt since almost two years earlier to the day in 1916 he might have been stationed in trenches near Hulluch, France when over 800 heavy German trench mortar rounds severely damaged the lines. After starting the club’s first five matches Currie slipped out of the first team and made only three more appearances the rest of the season. By January 1920 he was playing for Notts reserves and missed several chances in a 2-0 win over Hull City reserves. Later that year the Football Association suspended Currie for two months following an “incident” in a match against Leeds United.

Joe returned to the US on July 3, 1919, and was honorably discharged on August 11. He earned $8,135 for his military service plus train fare home to Chicago. Eventually he met a woman named Emma Koca and the two married on April 21, 1920. Joe continued working as a printer and playing soccer. He returned to his pre-war club Rangers and also occasionally lined up for the famous Sparta Club. Soon children came along – Joseph who lived for only a day in 1923 followed by Grace in 1925 and Robert four years later. The family had by then moved into one of the “Czech Bungalows” that lined the streets of Berwyn and were surrounded by family and friends.

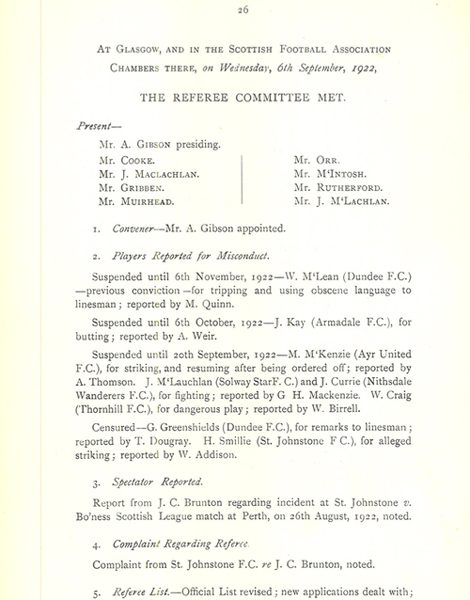

James’s whereabouts for the 1920-21 season are unknown, he may have continued on with the Notts County reserves, been injured or simply stopped playing. By the spring of 1922 however he had signed for Queen of the South F.C. In a 1-1 draw with Motherwell on April 15, Currie was one of the game’s better players. He consistently outwitted defenders and created multiple chances for his side before scoring his club’s only goal early in the second half. Less than a month later he signed for Nithsdale Wanderers. It’s unclear how many games he played for the club before he drew a two-week suspension for fighting from the Referee’s Committee of the Scottish F.A. It may have been the new ban or perhaps it was the fact that his brother had relocated to New Jersey, but whatever the reason Currie sailed on the S.S. Columbia from Glasgow for the United States on September 30, 1922.

Listing his occupation as a miner, Currie soon joined the famous Bethlehem Steel football club while also working as a machinist for the company. The team was just beginning the American Soccer League’s second season and Currie was one of many British imports in the side, including former Liverpool man Robert Terris and ex-Clydebank F.C. winger Malcolm Goldie. Ultimately Currie appeared in just three games for the Steelmen before contracting pneumonia on November 30. James Currie, survivor of the Battles of the Somme and Passchendaele, decorated war hero and professional footballer died in hospital in the early morning hours of December 1, 1922. The next day his teammates ran out 3-0 winners over Harrison.

Joe saw his daughter married in 1945 and his wife Emma pass away in 1947. Ten years later he relocated along with his daughter Grace’s family to a new house in North Riverside, Illinois. All the while he continued to return to his childhood home of Braidwood – to collect black walnuts with his grandchildren, smoke his pipe and hunt mushrooms like he did as a boy. Joe passed away on December 18, 1969 and was buried next to his wife and parents in the Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago.

A version of this essay was published at www.SoccerHistoryUSA.org on November 13, 2017.