Baltimore has a long history of playing football. Even before the creation of the association, rugby, and intercollegiate codes there were football clubs in the city. By 1860, the Cottage, Mount Vernon, Waverly, Olympic and the East Baltimore Hurling and Football Club advertised meetings and matches. What rules they used and whether they played against each other are questions that remain unanswered. In 1894, the city had a team in the short-lived American League of Professional Football. A cup competition began in the city in 1914 and was named for Henry Rowland, a popular local businessman and soccer coach. Teams still compete for the Rowland Cup, symbolic of the state championship.

The history of women playing football in the area is less documented. In 1894, students at Miss Carter’s School for Young Ladies at Catonsville, Maryland, had a go at football. Two sides, the Unquenchables and the Invisibles, played a chaotic game that involved a fair amount of both kicking and carrying the ball. They wore distinct uniforms with both squads outfitted in white sweaters with either a U or I on the chest. The teams donned toboggan caps and skirts with the Unquenchables wearing blue and the Invisibles in red.

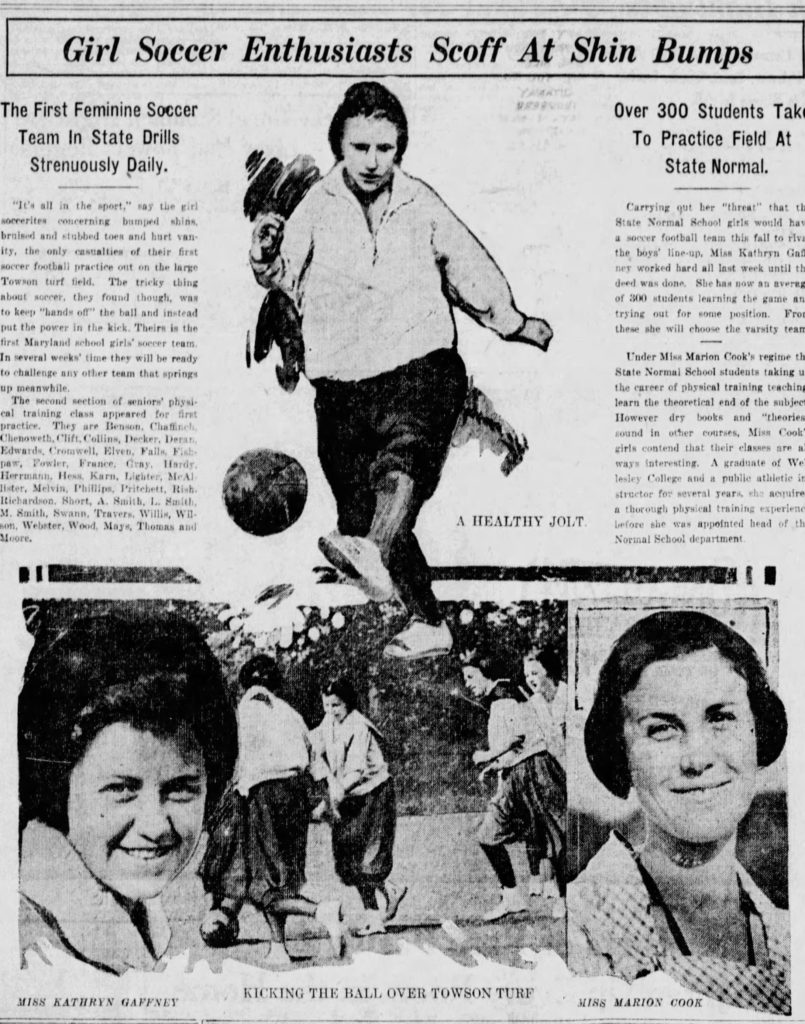

A few decades later in 1920, female students at the Maryland State Normal School (now Towson State University) began playing soccer. In the fall of 1921, a new coach arrived at the school named Katheryn Gaffney. A graduate of the Boston School of Physical Training, she had worked for Baltimore’s Playground Athletic League (PAL) for several years before joining the Normal. According to the Evening Sun, female students at the school decided that sports like field hockey and volleyball were “too mild.”[1] In other words, they pushed for the opportunity to participate in more active recreations. Gaffney undertook a process of determining who of the three hundred candidates would make the varsity squad. Less than a week later the newspaper published photographs of what they called the first women’s soccer team in the state at practice.

By November the Normal had scheduled matches against two different high school squads: Towson and Sparrows Point. First, however they were set to play an intramural game on Governor’s Day November 20 with the Honorable Albert Ritchie himself in attendance. Soon after they may have played the match against Towson High School, but there is no record of the result. In December the Sparrows Point High School team beat the Normal squad 3-1.

On October 22, 1922 the Dick, Kerr Ladies team of England played in Baltimore. They lost 4-3 to Baltimore Soccer Club, one of the city’s established male squads. At the same time, the teams from the Normal, Townson and Sparrows Point schools continued to play although details of the matches are lacking. In December, the Evening Sun announced two new women’s soccer clubs had formed. The Women’s Olympic Association of Maryland (WOAM) held their first practice in September or October and the Maryland All-Stars organized in mid-November. They were scheduled to play each other as part of a doubleheader on December 24, although it was eventually postponed due to poor conditions. The first match of the day featured the women’s teams while the nightcap was contested by two men’s clubs. During this period, it was extremely unusual, although not unique, to schedule women’s and men’s matches for the same day.

The organizing force behind the two new squads was named Edward Hill. Born Edward Hilkowitz to Russian-Jewish immigrants, he may have changed his name during his service in the US navy in World War I. He was employed by PAL and was especially involved in coaching girl’s swimming. An accomplished swimmer himself, he also worked as a lifeguard. One story in the Baltimore Sun on August 16, 1920 noted that he had saved at least thirty-five people during his career. A week later he raised the total to thirty-six after rescuing sixteen-year-old Joe Silver at Tolchester Beach. Although heavily muscled and clearly athletic, Hill suffered from health problems after being injured in the war and diagnosed with epilepsy. Such factors may have contributed to his early death on October 27, 1927.

The players on WOAM and the All-Stars came from Sparrows Point and other high schools around the area.

WOAM planned to also compete in a range of sports and a challenge notice from the club published in November 1922 declared they would face “any women athletic teams.”[2] Most of the soccer players were also accomplished athletes in other sports, especially track and field. Victoria Woodhead, for example, had a reputation as one of the fastest female sprinters in the state. She was the daughter of English immigrants and may have learned soccer from her father who grew up in Lancashire. Like several of her teammates, Woodhead came from a large family with four brothers and four sisters. Her father worked at a steel plant along with other WOAM dads; several more were employed by ship building facilities.

On match day December 31, 1922 the Evening Sun praised the quality of the players, noting that some of the squad’s better kickers could probably line up for men’s teams. High praise considering that the region had a quite active soccer community during this period. The game ended with WOAM taking home the honors after a 3-0 victory. A month later an extraordinary letter appeared in the Evening Sun. Authored by WOAM forward Audrey Matthews, it attacked Dr. William H. Burdick, head of the PAL. The missive was in response to a decision he recently made banning athletes who joined independent clubs from also playing on high school teams. Although the establishment of new soccer clubs may have played a role, the ruling was more likely in response to the formation of a girls’ basketball league. His objections were not totally clear but seemed to revolve around the dangers of amateur athletes competing against professionals.

Whatever the motivation, Matthews took Burdick’s ruling as an attempt to prevent young women from taking part in competitive and physically demanding sports. She questioned his motives “Is he promoting athletics or is he just holding us back from the thing that will make better women of us all?” She claimed that school gym classes were not vigorous enough and that “a girl who is an athlete is not afraid to get her hands or her middy dirty with the muddy ball; she is not so timid that she is afraid to charge her opponent when she is playing in a game opposite her.” She accused Burdick of trying to ban independent clubs because he knew that in a short time PAL athletics would no longer be able to compete against those outside the organization. Matthews continued by warning Burdick that “Girls will come to their senses. They will realize that they are handicapped by those bunglesome bloomers” and they will demand better athletic opportunities. She ended by encouraging others to write in and express their opinions “Are you in favor of major sports for women? Is it immoral for the players to wear [shorts] and long sleeve jerseys on the field of play? Come give us your answer through these columns.”[3]

I could find no evidence that Burdick responded publicly to the letter. The principal of Sparrows Point High School however was unequivocal in his support, declaring “at this time it is with pride that I give my endorsement to major sports for women.” He added that athletics had both physical and mental health benefits and that he had already seen “rapid improvement” in eight of the girls who joined WOAM.[4] The only other published reply came from a recent graduate of Eastern High School. Nelly M. Lewis defended Burdick saying that he had little to fear from WOAM. She rejected Matthews’s claims about the poor level of gym classes by stating that things had improved over time and that a wide variety of activities were available. Lewis doubted that many female students “will consent to appear in public in your beloved shorts and jersey” and if they did, they should not be surprised if the “fellows” made “passing remarks.”[5] The line suggested that if women athletes appeared in sporting attire other than bloomers and middys, they could not blame men from commenting on them.

As the controversy petered out, WOAM focused on other sports such as baseball and basketball during the spring and summer of 1923. The soccer club began practices again in October, but there is no record of any further games. Although short lived, the Baltimore women’s soccer clubs showed that young women craved more and better opportunities to express themselves through sport. Many of these female athletes continued to play and excel in other activities such as basketball, swimming, and track and field.

Endnotes

[1] “Hockey or Volley Ball Too Mild for Girls at Normal,” Evening Sun, October 8, 1921.

[2] “Women Issue Challenge,” Baltimore Sun, November 30, 1922.

[3] All quotes in this section from Audrey Matthews, “Girl Athlete Hurls Challenge at Dr. W.H. Burdick,” Evening Sun, January 30, 1923.

[4] “Sparrows Point Principal Favors Major Girl Sports,” Evening Sun, February 13, 1923.

[5] Nelly M. Lewis, “Eastern High Graduate Flies to Dr. Burdick’s Defense,” Evening News, February 1, 1923.