Today’s soccer players are bigger, faster and better trained than those of previous years. They also make a lot more money.

In 2014 Clint Dempsey was the highest paid player in Major League Soccer, earning a reported $6.695 million in that season. He was closely followed by other stars including Michael Bradley, Jermain DeFoe (both at $6 million) and Landon Donovan ($4.583 million). Although such figures were not typical for the league, the average salary was still a healthy $186,258 and even the lowest paid players took home at least $36,500. While not a lot of money compared to the top earners, the minimum salary, depending on individual circumstances of course, was probably still enough so that the players did not need to work at another job during the season.

Historically the ability to earn such wages in the US strictly by playing soccer was an impossible dream. Even professional athletes in the country’s top league toiled at other occupations as they competed on the pitch.

The Holyoke Falcos provide an interesting case in point. The club joined the American Soccer League (ASL) during its inaugural season in 1921-22. The team was based in Holyoke Massachusetts, an industrial community about one hundred miles west of Boston. Nicknamed the “Paper City” due to the number of paper manufacturers, Holyoke also had its share of textile mills. It was out of these industrial concerns, especially the textile companies where soccer clubs first emerged in the late 19th century.

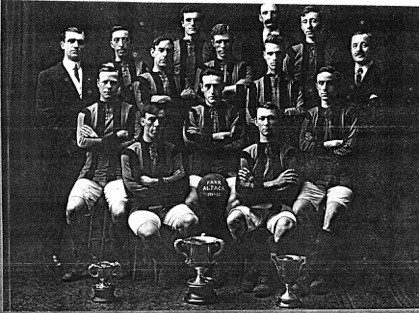

Farr Alpaca, the company that sponsored the Falcos, was founded in Canada and moved to the United States in 1873. To fill its factories with skilled workers the operation brought in employees from Canada and the British Isles. The company organized its first soccer team, appropriately named Farr Alpaca Football Club, in 1909.

Many of these early soccer players came from Great Britain, especially Scotland. Let’s take a look at eleven members, including eight players, the trainer, manager and team president of the 1911 Farr Alpaca squad. Only one of them, Frederick Arnold, was born in the United States and he was likely the son of the team’s honorary president John P. Arnold, who came from England. Of the remaining members of the squad, one other was born in England and the rest in Scotland. Three, or more likely four, worked for various firms in the city (including a paper company and a silk manufacturer) while Farr Alpaca employed all the rest. The company had a reputation as one of the highest paying companies in the city and it was also one of the first factories in Holyoke to have air conditioning. Jobs at the Farr were so coveted that sometimes entire families worked together in the mills.

Although the local league remained an amateur circuit, it is also clear that the firm used the promise of employment to lure talented athletes who could compete for the company. As an overseer, John Arnold held considerable power to make hires and he may have been responsible for recruiting many of the early soccer players. Such policies may explain why many of the men playing for Farr Alpaca in 1911 were listed simply as an “employee” of the company.

It’s impossible to know what work they actually performed although it’s unlikely that these were simply no-show jobs where they spent the bulk of their time in training. Instead these positions were probably unskilled, requiring little experience or training. Since the players could be paid for missing work time it may be that they tended to be placed in positions that could be easily covered when the team was playing or practicing. Other members of squad held named positions including pressman, dyer and singer. The latter did not involve music but was a position related to the process of making textiles. Despite having a specific designation, none of these positions paid particularly high wages. Nevertheless, they likely earned more than most industrial workers in the city.

By 1921 when the Falcos joined the ASL, its players, according to the terms of the league were regarded as professional soccer players. Nonetheless they still held positions off of the pitch.

Some things had changed since 1911, most notably the fact that of the twelve identified members of the squad five were American born while four came from England, two from Scotland and one was unknown but likely Scotland. Only three were confirmed as employees of Farr Alpaca while the others held positions as a woolsorter, loom fixer, and clerk, among other jobs. Once again some occupations, such as clerk or engineer, indicated middle class status but others like bricklayer, dyer, and paper maker did not.

Several of the players, including Alexander Moir (employee) and Walter Dowdall (dyer) resided at boarding houses near the center of the city. This may indicate the low salaries such men earned while playing professional soccer in 1921. Others such as Joseph Marriot, a loom fixer at the Farr Alpaca company, were skilled workers who made enough to own their own homes. Historian William Hartford called loom fixers “the most skilled and indispensable workers in the [the weaving] departments” of large textile mills. Despite his position as a homeowner and his relatively high status place in the industrial world of the textile mills Marriot was not likely a wealthy man. The house he owned at 85 Newton Street was a small brick rowhouse built in 1890 and not a mansion.

From the few details we can glean about the lives of these early professional soccer players they did not get rich playing the game. In fact all of them continued to work off the pitch and for many those jobs were likely low paying, industrial positions with little security — a far cry from the extravagant earnings of today’s top stars and still some distance even from the players on the margins of modern professional rosters.