In the midst of a growing influenza epidemic, on September 28, 1918, the city of Philadelphia hosted a Liberty Loan Parade aimed at supporting the American war effort in what is now known as the First World War. Some 200,000 people lined Broad Street for the parade. The parade proved to be a tragic mistake enabling the rapid spread of the influenza virus.

The flu had first appeared locally in the vast Philadelphia Navy Yard. On September 18, some 800 sailors were reported to be sick with the disease.[1] By October 1, only days after the parade, 635 new cases were reported in the city. With the outbreak rapidly spreading in other industrial centers such as Chester and Bethlehem, the state’s acting Commissioner of Health Dr. B.F. Royer announced the statewide closure of all places of public amusement on October 3. At the time the ban was issued, Philadelphia public health authorities estimated “at least 75,000” were infected in the city. Philadelphia’s Board of Health issued an order prohibiting “the assemblages of all persons in public and semi-public places.” All schools and churches were closed and work in the city’s factories began to grind to a halt. Funerals for those who succumbed to influenza or pneumonia were ordered to be private with only immediate adult relatives allowed to attend.[2] Within a week some 2,600 Philadelphians were dead. Young people in the city’s crowded industrial neighborhoods were particularly affected by the epidemic. By its end, Philadelphia had the highest number of deaths of any city in the country.[3]

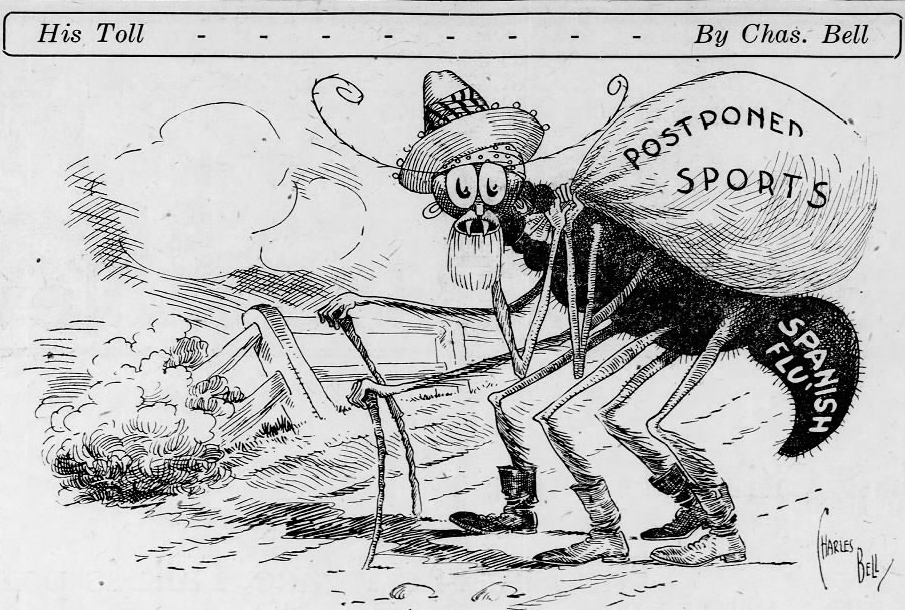

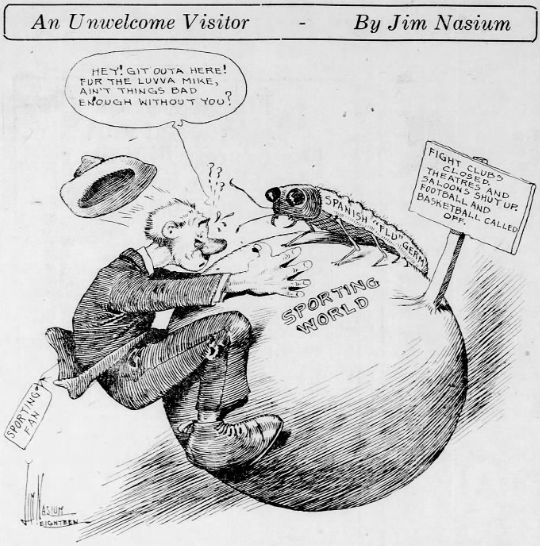

On the day of the parade, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on the opening match of the 1918-19 soccer season, a National Association Football League match scheduled for the next day at nearby Bristol, Pa. between the Merchant Ship Team A and the Babcock & Wilcox team of Bayonne, N.J.[4] As the influenza epidemic rapidly took hold, outdoor sporting events were canceled. The opening of the University of Pennsylvania’s football season, at the time Philadelphia’s premier sporting event of the fall season, was repeatedly postponed. According to one report a little more than two weeks after the Liberty Loan Parade, “Except for a few soccer games and golf matches the sporting world has been pretty well in the throes of the epidemic.”[5] But the epidemic’s effects on soccer were already present. Under the headline “Many Athletic Games For Today Are Off,” the Inquirer reported on October 5 the scheduled meeting between the Merchant Ship Team B and the Henry Disston team in the city’s Tacony neighborhood had been postponed “owing to the spread of the flu in that section of the city.”[6] But while “health authorities” would not allow that game to proceed, others were played as scheduled.[7]

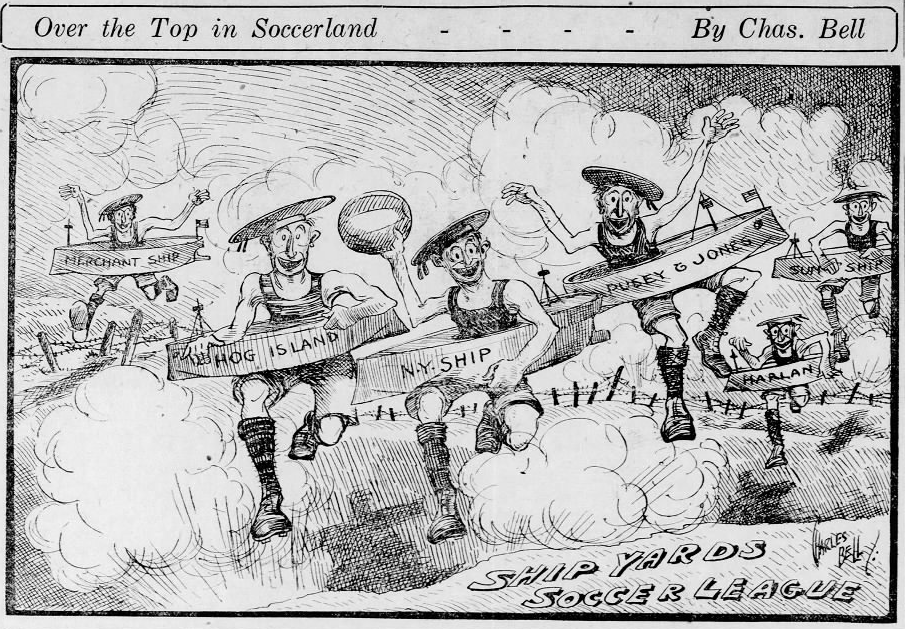

Two days after the report on the postponement of the Merchant Ship-Disston game, an Inquirer preview of the city’s newly formed Delaware River Athletic Association Soccer League (otherwise known as the Shipyard League), as well as the American League and Allied American League made no mention of the possible effects of the influenza outbreak on the start of league play. But a few columns away on the same page as the preview, another report noted the secretary of the Industrial League was “laid up with Spanish influenza” and that Douglas Stewart, president of the Football Association of Eastern Pennsylvania and District had “been seriously ill for the last few days.”[8]

Soon, death notices for soccer players and administrators began to appear. On October 9, the Inquirer reported that Vance Hall, an amateur player with Cardington before joining professional side Victors and “one of the best soccer players in the country in his prime,” was dead “from Spanish influenza after only a few days’ illness.” A week later it was reported that F.C. Wright, manager of the Pusey & Jones team of the Shipyard League had succumbed to pneumonia as a result of the flu.[9] The next day, a report said the Shipyard League had decided to postpone the start of its season “because of several of the players being laid up with influenza.” The Allied American League also postponed the opening of its season.[10] The American League disbanded.[11] Soon after, former West Philadelphia and Falls player Harry Kendall died “after a short illness from the influenza.”[12] The death of relatives due to the epidemic also had an effect on soccer. A report on sports at Germantown High School noted the captain of the school’s soccer team, Louis Johnson, had left the school after the death of his father.[13]

As the death toll rose nonleague games continued to be scheduled in the city with the sanction of local health authorities because “the epidemic ban had not been placed on out-door sports.” Indeed, it was asserted in one report on October 11 that outdoor sports “should be given every encouragement at this time.”[14] On October 17, a report described the Shipyard League as “badly crippled” and “hit badly by the Spanish ‘flu'” and noted while some games were canceled because of the epidemic other games remained as scheduled because “no official word” said they couldn’t be played.[15] While “national cup matches” were postponed “owing to the epidemic,” the start of the Allied American League second and third division seasons commenced on Oct. 19, albeit with just four games.[16] The next day came reports of the death from influenza of Charlie Turner, assistant trainer of Merchant Ship Team B.[17] During the week of October 13-19, the city’s health department reported 4,596 deaths due to the epidemic.[18]

Games played as scheduled were nevertheless affected by the influenza outbreak. Second team players filled the roster of the Sun Ship team in their match against the Germantown Boys Club “owing to the ‘regulars’ being ill with the ‘flu.’”[19] The administration of soccer in the city was also affected by the epidemic. The ban on indoor public gatherings resulted in planned meetings by officials of the Eastern District and Allied American League being indefinitely postponed.[20] Nevertheless, in the midst of the crisis, the Germantown Boys’ Club announced the formation of a new six-team Liberty Soccer League. The teams, composed of players under the age of 18, would play evening games at the Boys’ Club grounds, which had been “fitted up with big arc lights expressly for soccer at night.”[21]

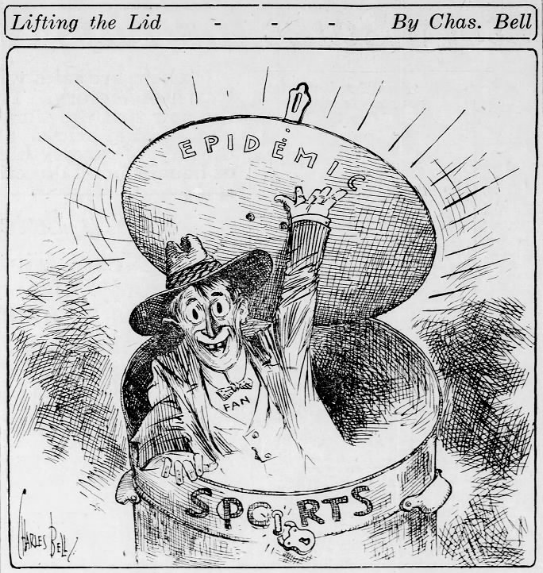

Curiously, the Inquirer report on October 21 on the formation of the Liberty Soccer League also states, “Soccer football will likely get going in full swing next Saturday [October 26] as it is expected that the epidemic ban will be lifted by that time on outdoor sports in this city,” this a day after the newspaper reported on games played in Germantown and the start of Allied American League second and third division play.[22] While the city enforced the ban on public gatherings, and the start of the University of Pennsylvania’s football season was repeatedly postponed, authorities allowed soccer games to be played in the city and elsewhere. It is unclear if the “epidemic ban” refers to the city’s leagues postponing the start of league play. But the epidemic itself was finally beginning to peak.

On October 28 public schools reopened. Two days later the closure of all public gathering places was lifted allowing bars and theaters to open for the first time in three weeks. Dr. Wilmer Krusen, the Director of Health and Charities of the city’s Board of Health who at the start of the outbreak had reassured the public “there was little fear that the disease would spread to any great degree among citizens” now said, “There can be no doubt that the situation has returned to normal.”[23] Since September 30, 11,811 Philadelphians had died as a result of the epidemic with nearly 50,000 cases of infection reported.[24] But while the epidemic had peaked its terrible toll continued. Within six months, fatalities numbered 16,000 and half a million cases of infection were reported among the city’s population of 1.7 million.[25]

The soccer season in Philadelphia officially opened on November 2 with fifteen games in and around the city.[26] Among the highlights was the opening of the Shipyard League season at the grounds at Third Street and Lehigh Avenue with the Hog Island team defeating Pusey & Jones, 3-2. In a first-round National Challenge Cup match at Disston Ball Park in Tacony, the Merchant Team B defeated Disston 7-5 after extra time, the teams playing to a 5-5 standstill after 90 minutes.

Notes

[1] “800 Cases Here of Spanish Grip; Naval Men Sick,” Evening Public Ledger, Sept. 18, 1918, 1

[2] “Theatres, Saloons in Penna. Closed to Halt Influenza,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 4, 1918, 1, 13.

[3] Mira Shetty and J.J. Ahern, “Penn and the 1918 Influenza Epidemic,” retrieved Mar. 16, 2020 https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/flu

[4] “First League Match,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Sept. 28, 1918, 14.

[5] “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 14, 1918, 12.

[6] “Many Athletic Games for Today are Off,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 5, 1918, 14.

[7] “Soccer Games Today,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 5, 1918, 14.

[8] “Soccer Season to Open Saturday,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 7, 1918, 14; “Corner Kicks,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 7, 1918, 14.

[9] “Soccer Champions May Play Navy,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 9, 1918, 12; “Soccer Magnate Dies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 17, 1918, 12.

[10] “Shipyards Soccer Opening Postponed,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 10, 12; “Soccer Games Postponed,” Evening Public Ledger, Oct. 10, 1918, 12.

[11] “Soccer Game Wanted,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 23, 1918, 12.

[12] “Soccer Player Dies,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 20, 1918, 19.

[13] “Reopening of Schools Starts Much Activity,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 29, 12.

[14] “Arrange Soccer Match,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 11, 1918, 14.

[15] “Flu Again Halts Soccer Contests,” Evening Public Ledger, Oct. 17, 1918, 12.

[16] “Soccer Games Today,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 19, 1918, 12.

[17] “Kicks from the Corner,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 21, 1918, 14.

[18] “Warm Rain Favors Influenza’s Spread,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 21, 1918, 6.

[19] “Two Victories for Germantown Teams,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 20, 19.

[20] “Corner Kicks,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 14, 1918, 12.

[21] “Six Soccer Clubs in Liberty League,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 21, 1918, 14.

[22] “Six Soccer Clubs in Liberty League,” 14. See page 19 of the Oct. 20, 1918 edition of the Inquirer for reports on the games played in Germantown and the start of Allied American League second and third division play.

[23] “Spanish Influenza Sends 600 Sailors To Hospitals Here,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Sept. 19, 1918, 2; “8 a.m. Wednesday Hour for Lifting Grippe Ban Here,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 28, 1918, 1, 5.

[24] “Ban Raised Here as Epidemic Ends,” Philadelphia Inquirer, Oct. 31, 1918, 8.

[25] Shetty and Ahern, “Penn and the 1918 Influenza Epidemic.”

[26] “Fifteen Soccer Games on Card,” Evening Public Ledger, Nov. 2, 1918, 14.

Pingback: Philadelphia soccer and the 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic – The Philly Soccer Page