It’s been a hot topic of late, the notion of bringing promotion/relegation to America. But believe it or not, it’s already been here and people have done that.

One instance of promoting a top team into an upper division while relegating a bottom finisher was accompanied by little fanfare 25 years ago, when it was practiced in the Pacific Northwest, not by professional clubs, mind you, but by collegians.

Back in the day before soccer was on the radar of most conferences such as the Pac-12, the Northwest Collegiate Soccer Conference (NCSC) provided the competitive and scheduling platform for nearly every program in Cascadia.

Formed in 1971, the NCSC was founded by seven men’s soccer programs, Washington, Seattle University and Seattle Pacific among them. As the game grew, however, women’s divisions were added, along with junior colleges. The men’s division mushroomed, peaking at 14 teams.

It was that explosion of growth and the disparity of programs that prompted the promotion/relegation discussion, recalls Cliff McCrath, then the head coach of Seattle Pacific and NCSC executive secretary.

McCrath says several NCSC coaches with British roots first raised the possibility in the mid-Eighties. “Their ideas were always very creative,” he says. “They were people who were accustomed to the promotion/relegation concept.”

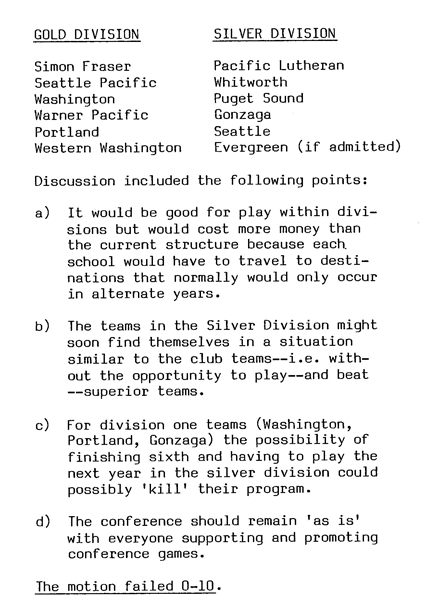

Proposals were brought to the annual meeting in 1986 and 1987 only to be soundly defeated. By 1988, outside pressure was brought to bear.

The University of Portland under Clive Charles was in rapid ascent mode. Kasey Keller, then a star for the U.S. youth national team, had joined the Pilots, helping them reach the NCAA Division I semifinals. Playoff selection and seeding was predicated partly on strength of schedule. Programs such as Portland or Washington or SPU (winner of four Division II championships between 1978-86) were paying a price for scheduling games with lowly, non-scholarship programs.

One D-I athletic director wrote that his school might withdraw from the NCSC unless divisions were created, resulting in fewer, more competitive games.

Peter Fewing, then a wide-eyed second-year coach with Seattle U., was trying to build a proper program after nine consecutive losing seasons at, first, the D1 and then NAIA levels. The coaching positions at UW and OSU, while appearing prestigious, were part-time, and the travel budgets did not accommodate air travel without fundraising.

In other words, “We were all just trying to make our way,” Fewing says.

McCrath and Fewing say the vote to split into divisions with promotion/relegation was matter-of-fact. “Nobody got upset or challenged anything,” McCrath contends. “I don’t remember anyone doing anything but applauding. It was a harmonious time.”

Fewing aspired to play the top teams, but he was realistic. While a player at Washington, Fewing’s Huskies had beaten Stanford, Cal and San Francisco, all away from home, and finished 14-3-2, yet did not earn a tournament selection. He understood the need for his alma mater and Portland needing to boost their RPI.

“The whole idea,” says McCrath, “was to keep that top division more regal and competitive.” His Falcons would win both the conference and NCAA championship in 1993.

As for Seattle U., they would use their time in the lower echelon to build a foundation for future success. “You want to test yourself against the best,” he says, “but you also have to learn how to win.”

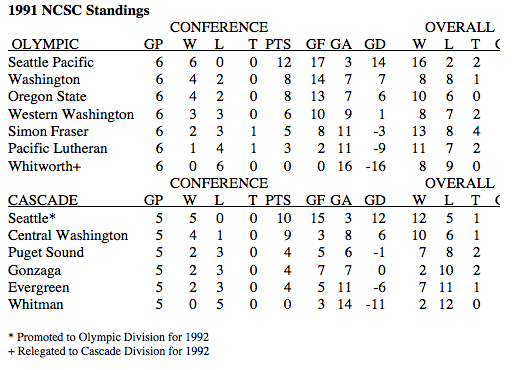

For 1989, D1 powers Portland and Washington were joined in the first (Olympic) division by McCrath’s D2 powerhouse Seattle Pacific and four NAIA programs: three-time champion Simon Fraser, Pacific Lutheran, Whitworth and Warner Pacific. Surprisingly, Whitworth finished with an identical 4-1-1 record to Portland, with the Pilots prevailing on goal differential.

While Western Washington, winner of the second (Cascade) division, was promoted, no relegation was necessary; Portland withdrew its membership at the next AGM. In 1990 relegation was avoided again; Warner Pacific left the league and Olympic Division and was replaced by Cascade winner Oregon State.

Finally, in the 1991 season, relegation became a reality. After twice finishing in the top four, Whitworth finished pointless in the top flight. Meanwhile, Fewing’s then-Chieftains won the Cascade by virtue of a 2-0 road victory over previously unbeaten Central Washington in the conference season finale.

Other than insiders, few knew about the promotion/relegation angle. And at the time, the trophy was more important than the promotion that went with it.

“We just wanted to win the doggone (division),” says Fewing. “The goal for us had been to get a trophy–our first trophy. Cliff got the conference some cool trophies, and it was something you wanted in your trophy case.”

It proved a seminal moment for Seattle University. Soon enough they would begin advancing to NAIA regionals. In 1997 the Chieftains won both their first conference championship and first NAIA national title. After moving to NCAA D2, they won a title there in 2004, going undefeated.

“It worked out great for us,” states Fewing.

In the meantime, NCSC membership began to decline. Gonzaga joined in Portland in the West Coast Conference, Washington and OSU went to the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation. After 1991 promotion/relegation was rescinded for two geographical divisions. Following the 1993 season the NCSC disbanded, with the D2, D3 and NAIA schools going to newly-formed multi-sport conferences within their affiliation.

When the NCSC flame flickered out, it marked the end of an innovative association that had fostered not only growth but excellence, if a program so wished. The promotion/relegation simply served the purpose at the time.

“The league was meant to die at some point,” McCrath concedes. “It was created to give order to an entire geographical area; it was all very pragmatic. And when it no longer was necessary, it went away.”

A version of this article first appeared at The Frank MacDonald Blog on October 21, 2014.

I believe there are American amateur and semipro leagues here and there that have had pro/rel for a while. The only one that I know of for sure is the Cosmopolitan League in New York (formerly named the German-American Soccer League) which has had it since at least the 1940s, maybe earlier. The GASL didn’t have pro/rel when the league was founded in 1923, but it did by the time of the earliest standings I’ve seen, in the 1947-48 season. The GASL seems to have started it for the same reason that it got started in England, too many teams.

Played college soccer during this time period on the East coast and know these teams, but not of the promotion and relegation. Very interesting to see it in the college game. Competitively, the next time I saw pro-rel was in the USLNJ Over 40 league. There are 4 divisions of 10 teams each. Here are the rules: “At the end of a competitive year, the two highest finishing teams from a less competitive division will be promoted to the next most competitive division for the ensuing competition year, and the two lowest finishing teams in a competitive division will be relegated to the next lower competitive division for the ensuing competition year.”