Our series of Q&A’s with Philadelphia-born US Soccer Hall of Famer Len Oliver continues.

SASH: You have great awareness of the heritage of Lighthouse as a producer of some of the best soccer talent both in the city and in the country. Was that something that you had at the time or did that come later?

Len Oliver: Being in the neighborhood, we just naturally thought of playing with Lighthouse Boys Club’s youth soccer program. Others were doing it so we just joined. Since our games were at Lighthouse Field, B St. & Erie Avenue, we just walked up there—about 3 miles, or took several trolley cars. Needless to say, we were ready to play when we arrived. E.g., I had never heard of a hamstring injury before adulthood. We came to realize the importance of Lighthouse to Philly youth soccer only later, when we realized that many of the pros on the Philly Americans and Philly Nationals were Lighthouse products.

SASH: I ask because that sense of local and national soccer heritage became lost in the US at some point, which is of course part of why you first wrote your article. That disconnect still exists for many Americans, whether they are fans of soccer or not. What is the importance of that heritage to you?

LO: When you are growing up in the neighborhoods, we didn’t think about our “soccer heritage,” we just found it convenient to play at Lighthouse. Our coaches were English and Scottish ex-players who wanted the kids to play without too much coaching. No coaching schools existed in the U.S., so these coaches taught us the game mostly by example. Outside of St. Louis, soccer in America in the1940-early 1960s was primarily urban ethnic. That’s what we thought soccer was, outside of our Philly neighborhoods—urban ethnic and it was true.

SASH: While the primary mission of Lighthouse was to provide beneficial services to North Philadelphia’s working class citizens, it became the city’s top producer of soccer talent. Nowadays, parents like your father who wanted their kids to become soccer players would travel for miles to get them in such an elite program. Did anything like that go on with Lighthouse when you were with them or were clubs more strictly neighborhood based?

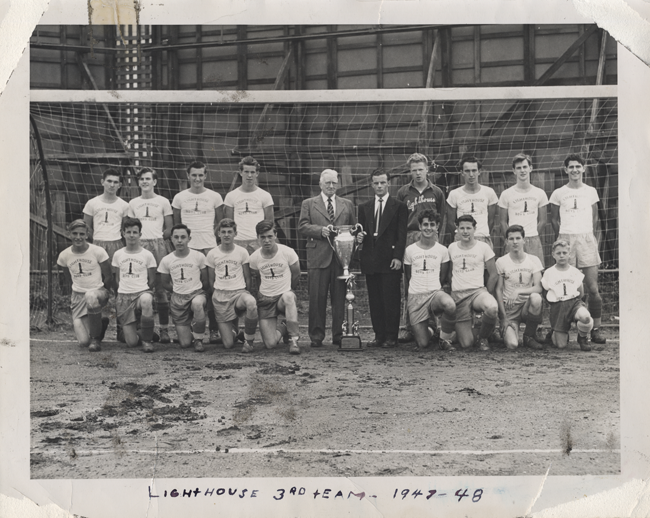

LO: You caught it right. We naturally gravitated to Lighthouse Boys Club for our soccer. It was really our only soccer outlet. Our soccer was Northeast Philly-based, with Lighthouse Boys Club as the hub. Once we emerged from the 10-12 year old Lighthouse divisions, we went to the Lighthouse Boys Club’s youth team—Lighthouse Juniors– playing throughout the city and beyond in U.S. Junior Cup play. I was 13 when I joined this team, coached by my pro-soccer playing cousin, Tommy Oliver, of the Philly Nationals in the old American Soccer League. Since there were no FIFA-age divisions at this time. we played regularly against 17-and 18-year olds. Sure, you were knocked about for a few games, but then you had to give it back in that rough-and-tumble youth soccer world or leave the game. We gave it back, winning two national junior titles, in 1947 by 1-0 against Shumacher of St. Louis at Holmes Stadium (decided in the last minutes on a direct corner kick into the goal!), and then in 1948 against Windsor of St. Louis by 2-1, in St. Louis, with all goals scored in the last three minutes. That was heady, never to be forgotten. These are the only scores I can remember from our Philly youth soccer experiences.

SASH: What did Coach Ozzie Lynn mean when he exhorted you and your teammates to play “the English game”?

LO: At this time, Scotland played a tough tackling game, but tried to build in finesse with passing combinations. The English style of the period was to drive the ball long, get it into the box for forwards to run onto. There was not a lot of finesse in our game. We tackled hard (there were no cards in the game at this time—the cards came on the scene in 1970), worked the ball around, but eventually drove it up field for our forwards to run onto. Remember, we played the old “two-back” game at this time, so we had five forwards and three midfielders to support every attack.

SASH: Could you tell me a little about your cousin, Tom Oliver, who played for Philadelphia Nationals?

LO: Tommy Oliver, our cousin, was about 10 years older than us. He played with the Philly Nationals from 1943-1953, winning four ASL Championships. He was a right winger, with a solid shot, scoring a number of goals. I believe he came up through the Lighthouse BC, and coached us in the late 1940s when we played with the Lighthouse Juniors, winning two national junior championships.

SASH: There is such a variety of tactical formations in use in the game today, some readers might be surprised to learn that the 2-3-5 was essentially the only formation used in the game for so long. Can you describe the 2-3-5 and how it worked? Where did you play within that formation?

LO: First, I played the old center halfback position, although on Lighthouse, playing against older players, I usually played right halfback. The English went to the “W-M” or “3-back game” in the late 1920s when the Offside Law was changed. You needed that extra player in the back. But the change didn’t come to America until the early 1950s, when teams dropped their center-half into the back line, meaning more work and running for the halfbacks and the inside forwards. My position was usually left-halfback, emulating one of our heroes at the time, Walter Bahr of the Philly Nationals.

Later formations included the Italian “Catenaccio” of the early 1950s, a defensive formation, the use of the 4-2-4 by Brazil in the 1958 World Cup in Sweden (my first World Cup—as a young GI I traveled by train to Sweden to see the games), the advent of the 4-3-3 by Germany in the late 1960s with Franz Beckenbauer as the “Sweeper,” then the 4-4-2 by numerous teams in the late 1970s, to today’s varied formations of 4-5-1, 4-2-3 1, and other modern innovations. The Dutch were truly the innovators of the period, with their concept of “total football” (everyone on attack, everyone on defense), always playing the 4-3-3 so they had consistent wing play.

SASH: You describe Lighthouse offering age divisions for players. Did you play against other clubs in these younger age division teams before advancing to the Lighthouse Juniors?

LO: We had strict age divisions in the Lighthouse Club soccer, but you didn’t start until you were about 10 years old—today’s U11 age grouping. Until that point, it was strictly ”street soccer” and “pick-up soccer”—for whoever showed up. We usually played on Helen Street, with garage doors as the goal, knowing you had to maneuver your brother, cousins, neighbors, the gas light, a 6-inch curb, and an occasional drunk named Riley. We learned soccer moves from this environment. We also used a Civil War cemetery for our play, using tombstones as goal posts. Innovative urban kids playing their adopted sport!

SASH: Who were some of Lighthouse’s rivals? What were some of the teams you looked forward to playing against?

LO: Our main rivals were Nicetown in North Philadelphia, Thomas Celtic near the Allegheny Avenue corridor, Erzgebirge—the German club, and youth teams sponsored by the various ethnic clubs—Italians, Hungarians, Ukrainians, Latvians, and other sponsors of their beloved youth soccer teams.

SASH: What were the colors of the the Lighthouse kit?

LO: We wore white button up shirts, completely different from the modern pull-over jerseys. In many cases, they were “hand-me-downs” from older teams. But they won championships.

SASH: You describe in the article that “We were low-income kids” whose equipment consisted of hand-me-downs. Given Lighthouse’s location in Northeast Philly, I’m assuming most of the players were first or second generation kids from the largely English, Irish and Scottish immigrant neighborhoods that worked in the factories in that area. Can you tell me more about the backgrounds of your Lighthouse teammates?

LO: You caught it right! Most of us were sons of immigrants (girls simply did not play soccer at this time) who worked in the textile mills and lived in the row house neighborhoods. We all came from similar ethnic backgrounds. For equipment, we used balls formerly played with by the senior clubs, like the Kensington Bluebells where our Father was a trainer who brought home equipment. Even our cleats, the famous Mansfield and Hotspurs’ lines, with “nail-in studs,” were often hand-me-downs as we couldn’t afford new shoes. For shin pads, our favorite was “Popular Mechanics,” a thick popular magazine that when torn in half constituted our pads. You could even read it at half-time. I hadn’t thought about it, but I assume the other ethnic junior clubs also used “hand-me-down” equipment from their senior teams.

SASH: Was there a sense that playing soccer was part of your ethnic heritage or was it simpler than that, that you were simply playing the sport that you had fell in love with through your watching your father and others in your neighborhood play. (I think I’m trying to get a sense of the place of soccer and Lighthouse in the community when you were growing up.)

LO: Most of the men in our ethnic community—German, Scots, English, and Irish—had played some soccer in the “old country,” passing the game on to their sons. Even third, fourth generation American youngsters, seeing us play the sport first in the streets and then with Lighthouse, joined in, so it wasn’t strictly ethnic. Few of our neighbors knew about Lighthouse Boys Club, as it was somewhat removed over on Front Street and Lehigh Avenue. There was nothing like it in our immediate neighborhood, and we only heard about Lighthouse, and the opportunities the Club offered to play organized soccer, through our Father and cousin’s relationship to the game.

SASH: You mentioned in the first interview that you were playing school ball during the week. At what school (s)was this? Was there an organized school league separate from the Philadelphia Soccer League? Was one league more competitive or prestigious than the other?

LO: We played at Northeast High School, 8th Street and Lehigh Avenue, as the natural school outlet for our soccer interests. Northeast, an all-boys school now moved to a new location in upper Northeast Philly and turning co-ed, was a known power in Philadelphia high school soccer. Yes, there was a public high school league, with our main opponents being Central High School, Frankford High, and occasionally West Philly High School. Since Northeast always was a home for the Lighthouse contingent, including Walter Bahr, we went 96 games without a defeat by the time Jim and I left in 1951. Our major rivals were in the private schools, especially Girard College, a perennial power in soccer, and we went head to head with Girard in the city finals for the three years we were at Northeast.

After every season, they named an “All-Scholastic Soccer Team,” competing against an All-Star team from the New York schools in an annual competition.

Five of us went on to play under full scholarships with Pete Leaness at Temple University, winning the Intercollegiate national title in my freshman year in 1951, defeating the University of San Francisco in Kezar Stadium 2-0 before a crowd of 10,000 home fans. We won the National Title again in 1953 with roughly the same team. A number of us were named to the National Soccer Coaches Association of America (NSCAA) All-American Intercollegiate Soccer Team since NCAA had not yet fully recognized soccer.

Just a few years ago, I was told the story from Philly that one of the referees told Pete Leaness to give five of the Northeast boys full scholarships to Temple, and that by doing so, he would win the National Championship. He gave us the scholarships, enabling low-income kids to attend college, often the first in our families to do so, and indeed he did win several national championships. Ah, fate!

SASH: Can you tell me about Holmes Stadium, where you the National Junior Challenge Cup for the first time.

LO: Holmes Stadium was just west of Kensington Avenue on Erie Avenue. It was an enclosed professional soccer stadium, host to ALS league games, US Open Cup games, and some international games. It had stands seating, I would guess, around 1,000 fans.

SASH: You mentioned making the US Olympic team as an alternate in 1952 and being told to come back in for years, “and that’s another story.” What happened in 1956?

LO: Long story. I came back in 1955, preparing for the U.S. Olympic Team tryouts, when I broke my left fibula against Ludlow Luistano in October, 1955, causing me to miss the Olympic team once again. Disappointed, but I was taken into the U.S. Army, played at Ludlow in 1956, played in San Francisco with the SF Mercury for a season while studying Romanian at US Army Language School in Monterey, and then sent to Germany where I played two-and-a-half years with a German side in Inn-Chimsee and with the U.S. CISM team in 1958 and 1959. [CISM is the acronym for Conseil International du Sports Militaire. Founded in 1948, it is the second largest sports organization in the world after the International Olympic Committee.]

While with the U.S. CISM team in 1959, as Captain, we were to participate in the tryouts for the U.S. Olympic Team in 1960. I caught mononucleosis in Belgium just before a game with Belgium, came over to the States with team, but again, for the third time, missed the tryouts. Disappointed, I returned to my German base, kept playing with my German team, determined to make the U.S. Olympic Team next time around. At the tryouts in St. Louis in December, 1962, I made the U.S. Pan-American Team to Brazil in April, 1963 and the U.S. Olympic Team for qualifying rounds in Mexico in 1964. A long, but rewarding soccer journey!

SASH: What are your thoughts on the recent rule from the US Soccer Development Academy that players on clubs in the Development Academy system cannot play on their school team?

LO: I understand the reasoning behind US Soccer’s dictum on Development Academy players not competing on their high school teams, but I am uneasy with the ruling. Some of my fondest memories in soccer came from my high school days, being recognized both in Northeast High School and in the larger community for our exploits. Our social standing in school, because of soccer, was unparalleled. We received great attention and recognition in the school paper and in assemblies, all contributing to our being awarded scholarships at Temple University. Not all the youngsters in the Developmental Academies will make the pros. In the meantime, I think they will have lost something valuable, never to be regained, by not playing with their high school soccer teams.

A version of this Q&A originally appeared at the Philly Soccer Page on December 19, 2012.