On Monday, September 21, 1953, police were called to the Garden Court Apartments at 47th and Pine Streets in West Philadelphia. The previous day, relatives and friends had repeatedly telephoned the four-room apartment on the third floor but the 55-year-old man who lived there had not answered. Increasingly anxious, an aunt contacted one of the man’s friends, who in turn contacted the building’s resident manager.

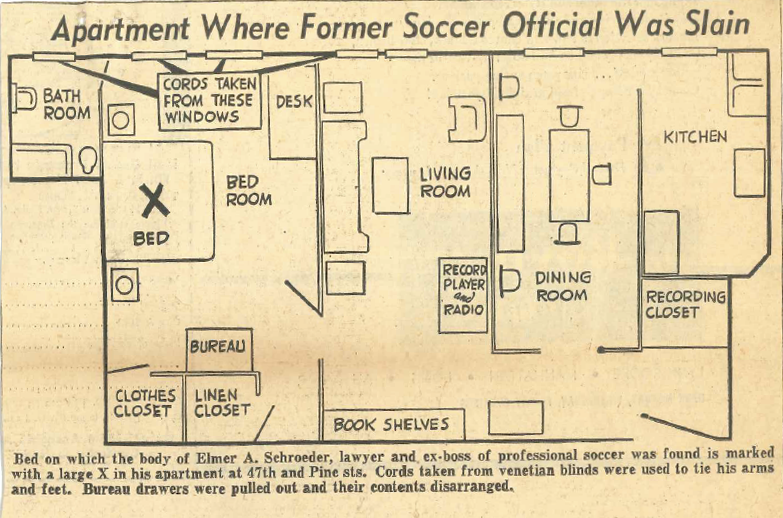

All of the lights were “blazing” when the resident manager used a passkey to enter the apartment, which had been “neatly ransacked.” Inside the bedroom on a bed that had not been slept in, the manager found the battered body of apartment’s resident, fully clothed and tied face up to the bed with cords cut from Venetian blinds in the apartment’s living room, bedroom, and bathroom. The man’s hands were bound behind his back. The cord around the man’s feet, which were crossed at the ankles, was secured under the bed. Around the man’s neck “looped into a garrote” was another cord lashed to the bed’s headboard. A sock had been stuffed into the man’s mouth, held in place by a torn bath towel tied around the man’s face. Two blows — “evidently…vicious, brass knuckle blows” — had crushed the man’s skull, one to the top of the head, the other to the left temple. When the body was later examined, heavy bruises were found on the lower part of the body, “particularly about the hips and thighs.” The man had been dead for at least 24 hours. Detective Captain Bartholomew Gorman said, “It’s one of the most vicious killings I’ve ever seen.” [1]

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “Robbery, detectives speculated, was at least one motive for the killing [emphasis added],” while the Courier-Post reported “robbery did not appear to be the primary motive,” the implication being the murder was sexually motivated. Writing in City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia, 1945-1972, Marc Stein describes how subsequent coverage of the crime — sometimes explicitly, sometimes more subtly using the coded language of the day — suggested the victim had been gay. “Unmarried,” he had “lived alone” in “bachelor quarters” variously described as “lavishly furnished,” “richly decorated,” “richly furnished,” “expensively furnished,” and “swank.” The man had been seen at a gay bar in Center City in the company of “young men” shortly before he was murdered. Of initial interest in the murder investigation was a “young man,” a “male companion” who had briefly lived with the victim. Soon, reporting described “striking parallels” with several other unsolved murders of gay men in the city, with the Philadelphia Daily News writing, “Circumstances of all three slayings indicate that the murderer of each man had been on fairly intimate terms with each victim.”[2]

The man found brutally murdered at the Garden Court Apartments was Elmer A. Schroeder, a prominent lawyer. Two decades before his killing Schroeder became the first native-born American to be elected president of the United States Football Association (U.S.F.A.), known today as the United States Soccer Federation.

–o–

The only son of German immigrants, Elmer A. Schroeder was born in Philadelphia on February 25, 1898. Growing up in Philadelphia’s Fairhill neighborhood, Schroeder graduated from Northeast High School. Attending Wharton at the University of Pennsylvania, Schroeder received an undergraduate degree in 1920, going on to earn a degree in law there. He maintained connections with his alma mater after beginning his law career in Philadelphia, receiving an appointment as an Instructor of Political Science in 1928 and later at Penn’s Law School.[3]

While an undergraduate at Penn, Schroeder began working with Lighthouse Boys Club, soon becoming the director of the organization’s soccer program. Under his stewardship, Lighthouse became the premier producer of Philadelphia soccer talent. By 1925, the Philadelphia Inquirer observed Schroeder “deserves credit for the untiring manner in which he boosts the dribbling game among the youngsters.”[4] The next year, Schroeder organized the first interstate junior soccer games to be played in Philadelphia.[5] By 1927, Schroeder, “manager general par-excellence,” was overseeing some thirty teams at Lighthouse, from youth sides to senior amateur sides.[6]

Schroeder’s success as an administrator at the club level was quickly recognized. In 1923 at the age of 25, he was elected to the executive board of the Middle Atlantic Boys’ Club Federation.[7] In 1925 he was elected to the Rules Committee of the Football Association of Eastern Pennsylvania and District (Eastern District), the governing body for soccer in the region, now called the Eastern Pennsylvania Soccer Association, and was also named as the organization’s delegate to the U.S.F.A.[8] A year after becoming a delegate, Schroeder was elected Third Vice President of the U.S.F.A. before being elected First Vice President in 1927.[9] One local report noted that between his duties managing Lighthouse Boys’ Club and at the U.S.F.A. headquarters in New York City, Schroeder ‘is thinking seriously of doing all his traveling through the air. All of which means that Mr. Schroeder may at some future time become recognized as a second Lindy.”[10] By the end of the decade, he was also serving as treasurer and vice president of Eastern Pennsylvania and District, and as president of Philadelphia’s top league, the Pennsylvania League.[11]

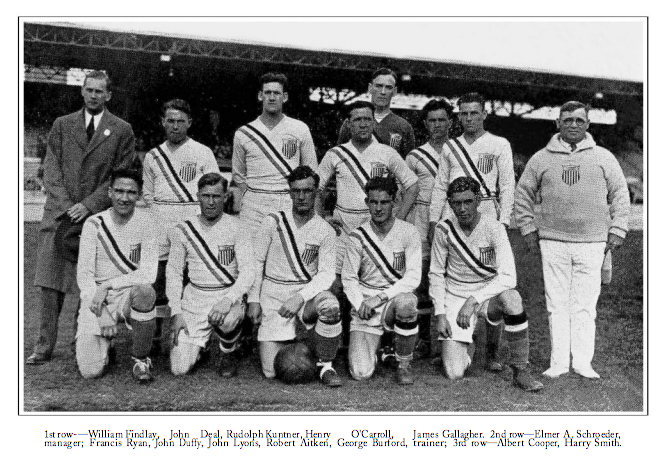

In 1928, Schroeder was appointed manager of the U.S. soccer team for the Olympic Games in Amsterdam. The Pittsburgh Press noted the appointment was “sufficient to raise eyebrows,” adding, “this admittedly bright and charming young man is practically untutored in the big things of soccer and cannot tank with other persons in ability and prestige.”[12] Moreover, while it was believed that a team of professional American players could capably acquit itself, there were concerns whether amateur soccer in the United States was sufficiently developed to realistically compete against more developed amateur sides from other countries which, “in many instances…are in a position to select just as powerful teams composed of simon pures as a team of profs.” Some even suggested it would be best if the U.S. did not send a soccer team to the Games.[13]

The U.S. team, which included from the Philadelphia area four players as well as the trainer, trained at the Ajax grounds in Amsterdam, playing two warm-up games against the Dutch side, the first finishing as a 1-1 draw, the second a 6-6 draw. On May 29, the U.S. faced South American champions Argentina, a team that had spent a long period before the Olympics playing warm-up games and believed by many to include professional players. Twenty-five minutes into the game and already trailing 2-0, the U.S. goalkeeper was injured and suffered a concussion. Schroeder wrote in his report to the U.S. Olympic Committee that “only spirit and courage enabled him to continue in a dazed condition.”

Argentina finished the game 11-2 winners and the U.S. was out of the Olympics. Schroeder reported, “It can be candidly stated that America could have produced no combination, amateur or professional, that could have carried the colors into the second round with Argentine as an opponent in the first.” Schroeder noted the team “lost gracefully and as true sportsmen…in a manner which was an honor to the country they were chosen to represent.”[14]

When the U.S.F.A. met in Milwaukee at the end of June, Schroeder’s report on the Olympic team, which played a series of games in the Netherlands, Germany, and Poland after the tournament, received “enthusiastic endorsement from al [sic] but those who had fondly expected to have his place.” The Pittsburgh Press declared, “The selection of Elmer Schroeder as manager of the Olympic team proved to be a satisfactory one after all.”[15] Among the recommendations Schroeder made after the Olympics was increasing the number of players sent to future games from sixteen to twenty-two “to facilitate training, to permit exhibition games to be played frequently and to guard against weakening the team by injuries.” In 1930, Schroeder joined the U.S. team in Uruguay as the U.S.F.A representative at the first World Cup.[16] There the team, made up entirely of professional players save for Philadelphia’s James Gentle, advanced to the semifinals where they were defeated 6-1 by Argentina in a game once again affected by injuries to U.S. players.

–o–

Newspaper reports indicated Schroeder was last seen alive around midnight at a downtown bar on Quince Street near Walnut Street on Saturday, September 19, accompanied by another man known to the witness.

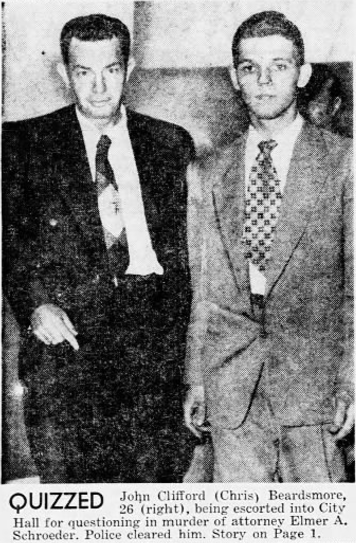

But of immediate interest to the police were the whereabouts of another man, described in newspaper reports as “a companion” who had lived with Schroeder at the Garden Court Apartments for a time until just before the murder. A day after the first reports of Schroeder’s murder, James Clifford Beardsmore was picked up at his “well furnished” one-room apartment at Delancey Place near 21st Street and after eight hours of questioning was released by the police. The 26-year-old told police he had first met Schroeder at a party earlier that summer. When Schroeder became ill in July, he suggested that Beardsmore move in with him until he recovered. Beardsmore did so but only after stipulating that he would pay part of the rent because he “didn’t want to be a moocher.” He said he had not seen Schroeder since September 1, although he had spoken to him on the phone.

Perhaps because of his recent illness, friends told police that Schroeder had not been drinking for some time until just before his murder. Fred Jordan, manager of the bar and restaurant at the Garden Court Apartments, described Schroeder as a regular patron who “had run up a bill of $165 at the time of his death.” Not that Schroeder wasn’t good for the tab. Jordan recalled on one occasion, “Schroeder was at the bar with two young men and displayed a check for $10,000 which he gave to one of his companions to deposit for him in a bank.”[17]

While police worked to establish Schroeder’s final movements before his murder they also examined his long-distance phone records and removed ten large cartons of business and personal papers from his apartment for inspection in an attempt to establish a motive for his murder. Police said they had received some fifty letters from people who knew Schroeder and wanted to help the investigation. On September 26, more than one hundred people attended Schroeder’s funeral at Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill.[18]

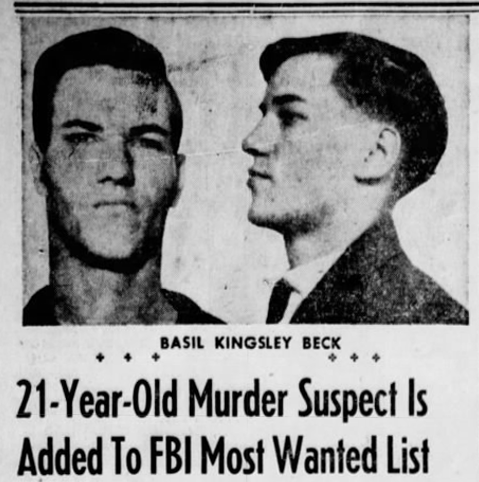

On October 10, Philadelphia police issued a national alert naming Basil Kingsley Beck, a 20-year-old escaped convict, as the number one suspect in Schroeder’s murder. On September 5, Beck and three other convicts had broken out of the Labette County jail in Oswego, Kansas after overpowering and disarming Undersheriff Arthur Hendrix before escaping in his car. Four days later, the convicts were spotted in Trumann, Arkansas. In the gun battle that followed one of the convicts was killed, and two others were captured. But Beck had already parted ways with his fellow escapees.

Stealing cars, according to police, Beck made his way to Philadelphia. “Waitresses, bartenders and several patrons” among the 135 acquaintances and friends of Schroeder questioned in the investigation identified him as “an almost constant taproom companion of Schroeder during the last days,” with the pair last seen together on September 18, three days before Schroeder’s murder. A Philadelphia newspaper report said Beck “moved from rooming house to rooming house,” and was last seen on October 5, “making the rounds of Pine and Spruce St. taprooms, apparently alone.” A nationally syndicated report said Beck “visited places frequented by homosexuals.”[19]

On March 1, 1954, his 21st birthday, Beck was placed on the F.B.I.’s Ten Most Wanted List. Two days later, he was arrested in San Pablo, California, where he had been working for several weeks at an auto supply shop under an assumed name.[20] He was returned to Oswego to face charges related to his escape. While awaiting trial, another jailbreak occurred but this time Beck did not join the three prisoners who escaped. Instead, he helped to free Sheriff John Burris, who had been locked into a cell after being overpowered in the escape.[21]

When questioned about the Schroeder murder, Beck acknowledged he had been in Philadelphia but said he knew nothing of the murder and had “never heard of the attorney.” On April 9, he was sentenced to a minimum of 27 years for the charges related to his escape. But police in Philadelphia did not request his extradition for the murder of Schroeder.[22]

Police soon had another suspect in Schroeder’s murder. On April 29, Francis X. Ballem was arrested by Upper Darby police after a trunk was left at the Sharon Hill trolley stop containing the dismembered partial remains of a man later identified as John Dopirak, a World War Two veteran from Chester who sometimes worked as a merchant seaman.

Ballem, who was carrying Dopirak’s legs in a suitcase when he was arrested at his home, quickly confessed and led police to Naylor’s Run in Upper Darby Park where he had earlier disposed of Dopirak’s lower torso. But he claimed not to know his victim’s name. Identification of the remains was delayed because, before dismembering the body with a carpenter’s saw, Ballem had burned his victim’s face and hands with a blowtorch and then covered the remains in lime and camphor before wrapping the body parts in plastic raincoats. Ballem told police he had met Dopirak at an orange drink stand at 12th and Market Street in Philadelphia before spending much of the rest of the day at a hotel bar at 13th and Filbert. After that, the pair went to Ballem’s home in Bywood where Ballem shot Dopirak, staying with the body for two days before dismembering it. Ballem later claimed self-defense although he admitted he planned to rob his victim. Asked about his “predilection for taprooms,” Ballem reportedly told police he was doing research for a book “about those places and the people who frequent them.”[23] Police investigated for a link between Ballem and four unsolved murders of gay men including Schroeder but had no success connecting him to those crimes.

While “numerous suspects were picked up but released for lack of evidence,” Schroeder’s killer was still at large.[24]

–o–

With his increased involvement in soccer at the national and international level, Schroeder stepped down from Lighthouse in 1931, although his involvement in Philadelphia soccer continued as president of the Pennsylvania League. On June 18, 1932, Schroeder was elected president of the U.S.F.A., becoming the first American-born president of the national governing body.[25] In addition to the election of Schroeder, a prime order of business at the U.S.F.A. convention in Baltimore was a move to return professional soccer to the control of the U.S.F.A. The country’s leading professional league, the American Soccer League (A.S.L.), had begun play in the fall of 1921 with great expectations. But disputes between the league and the U.S.F.A soon followed, culminating in the Soccer War of the 1928-29 season. The U.S.F.A declared the A.S.L. an outlaw league and backed a new professional league, the Eastern Soccer League. Matters were not helped by the advent of the Great Depression, and by the time of Schroeder’s election, the A.S.L. was on its last legs.

On November 19, 1932, Schroeder announced that a Philadelphia team would play in a new A.S.L., with the team largely based on the Disston club, the team he managed in the Pennsylvania League. Disston was made up of “the pick of the local district” and, perhaps because of Schroeder’s involvement with the 1930 U.S. World Cup team, included Bert Patenaude, the first player to score a hat trick at the World Cup.[26] Backing the team would be the city’s German American club, which gave the team its name, with games played at 8th Street and Tabor Road.[27] The German Americans, whose players retained their amateur status in the professional league, had a rough start in their first season in the A.S.L., finishing bottom of the table. But the team advanced as far as the quarterfinals of the 1933 National Challenge Cup, known today as the U.S. Open Cup, and won the National Amateur Cup with a 5-1 victory over Pittsburgh’s McKnight Beverage team on April 23, 1933. The same year, Schroeder’s proposal that all amateur players registered with the U.S.F.A. must pay a registration fee was unanimously adopted at the federation’s annual meeting.[28] The German Americans won the amateur title again on April 21, 1934, with a 2-1 win over another Pittsburgh team, Heidelberg S.C.

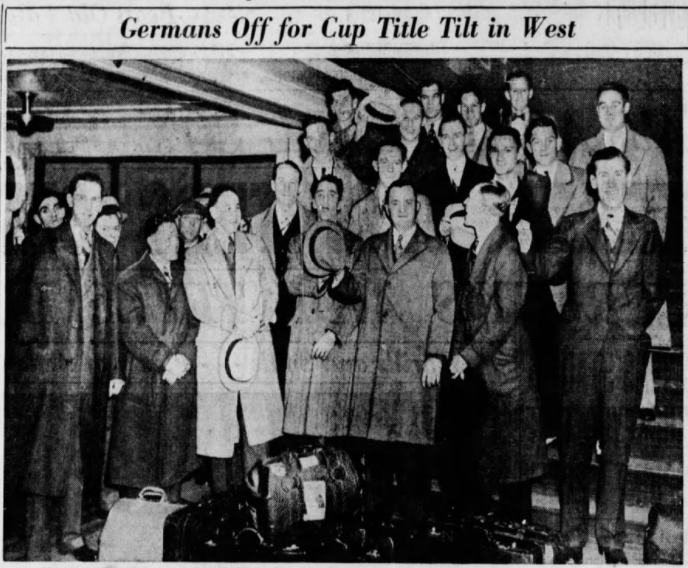

One week before the German Americans won their second national amateur championship, Schroeder was named as manager of the 1934 U.S. World Cup team, which included five German American players on the roster. The team’s coach was David Gould, assistant coach of the University of Pennsylvania’s soccer team.[29] Because the U.S. had been late in applying to enter the 1934 World Cup in Italy, the team was required to face Mexico in a playoff game on May 24, 1934. The U.S. won 4-2, with all four goals being scored by Aldo “Buff” Donelli. The U.S. team then had the misfortune of drawing host country Italy for their first game in the single-elimination tournament. On May 27, Donelli scored the lone U.S. goal in the 7-1 defeat to the eventual World Cup winners. Out of the tournament, the U.S. team played a short series of friendlies in Germany before returning home.[30]

At the annual U.S.F.A. meeting in July following the 1934 World Cup, Schroeder announced he would not stand for re-election as president “because of pressure of business.”[31] Nevertheless, less than a month later, Schroeder was appointed by the U.S.F.A. to oversee the new A.S.L., with the Philadelphia Inquirer referring to him as “the ‘Judge Landis’ of professional soccer,” a reference to Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the former federal judge who was Commissioner of Major League Baseball. At the same meeting, Schroeder was named chairman of the U.S. Olympic Committee on Soccer and a member of the U.S.F.A. appeals committee.[32]

Schroeder’s German Americans bounced back from their last-place finish in the 1933-34 A.S.L. season to win the 1934-35 championship, finishing with 18 wins, three losses and one tie, six wins better than the second-place New York Americans. Although they finished the 1935-36 A.S.L. season in fourth place, on May 3, 1936, the team defeated St. Louis Shamrocks 3-1 in Philadelphia after a 2-2 draw in St. Louis on April 26 to become the first amateur team to win the U.S. Open Cup. A few weeks later, the German American’s were defeated in the semifinals of the National Amateur Cup in their bid to capture a third national amateur championship.[33]

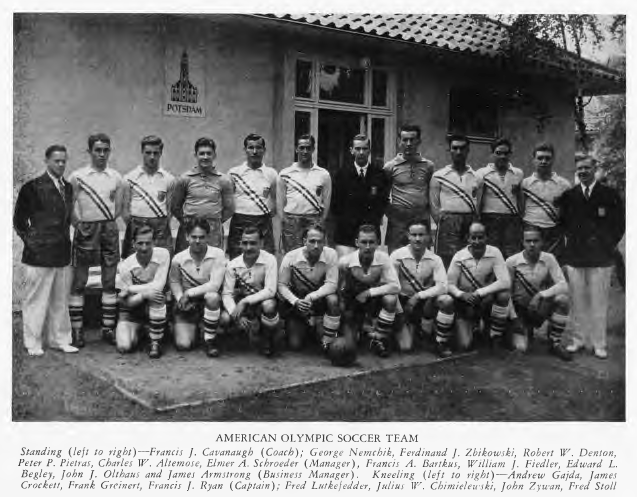

The success of Schroeder’s amateurs meant the U.S. squad for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin was largely made up of players from the German Americans, but the team was still short of the money needed to finance the trip. At the annual U.S.F.A. meeting only weeks before the team was set to depart for the Games, a speech by Schroeder proved to make the difference. The Pittsburgh Press reported the “masterful portrayal of his subject swung a rather hesitant, and in some quarters defiant meeting, into contributing $2,000 towards the cost of sending an Olympic soccer team to Berlin”.[34] Schroeder was again manager of the team and, once again, the tournament utilized a knockout format. Unfortunately for the U.S., they were again paired with Italy for their first game and lost, this time 1-0, in a game marked by rough play by the Italian side.[35]

A little more than a month after the U.S. team returned home, Schroeder announced the German Americans would turn professional, save for one player who was still a student at Temple University.[36] In July 1937, Schroeder stepped down from managing the German Americans in order “to take a much-needed rest.” One report said that under Schroeder, the team had “compiled the greatest record of any soccer outfit in this country.”[37] Schroeder’s rest was brief. In September he managed the U.S. team that traveled to Mexico for three games.[38] In October, Schroeder served as the arbitrator in a dispute between the U.S.F.A and the U.S. Referees’ Association.[39]

Schroeder was elected president of the A.S.L. in July 1939, a position he held until 1942, during which time he was also chairman of the U.S.F.A.’s Foreign Relations Committee.[40] A month later he returned to club soccer and the Pennsylvania League, managing the Trenton Americans, which was used as a farm club for the German Americans.[41] After the start of the Second World War, the Philadelphia German-Americans became the Philadelphia Americans. Now under manager Emil Schillinger, the Americans won the 1941-42 A.S.L. championship. As the 1943-44 champions, they were presented with a new trophy, the Elmer Schroeder Cup, donated to the league by the team’s former manager.[42] The “Amerks” won the championship again in 1946-47 before Schroeder returned as manager for the 1947-48 season, winning the championship once again before stepping down after the season “due to business.”[43]

On March 3, 1951, the Philadelphia Old Timers Association, the founders of the National Soccer Hall of Fame, inducted Schroeder into the Hall.[44] Two-and-a-half years later, Schroeder was murdered in his apartment.

–o–

Almost exactly two years after he was murdered, Philadelphia police named a new suspect in Schroeder’s killing, Thomas Wetling, a 20-year-old sailor assigned to the destroyer U.S.S. Hale. Wetling was implicated by another sailor who was being questioned by the F.B.I. in an unrelated investigation. According to the informant, Wetling and Schroeder knew each other. After a night of drinking, Wetling accompanied Schroeder to his apartment where they quarreled “about money and other things” before Wetling committed the murder. The Office of Naval Intelligence then placed Wetling under surveillance. When authorities used the pretext of issuing new identification cards to take a photograph of the suspect, Wetling became suspicious and jumped ship without a pass when the destroyer was docked in New York City. Apprehended two days later, he was placed in the brig while the ship traveled to its homeport in Rhode Island. There he was then questioned by Philadelphia police, who noted Wetling bore “a striking resemblance” with the previous suspect, Basil K. Beck.[45]

Wetling at first denied being in Philadelphia at the time of Schroeder’s murder. He then acknowledged he could have been in the city but did not confess to the murder. At a bail hearing, it was revealed the informant whose information led to Wetling’s arrest was James Clifford Beardsmore, the former roommate of Schroeder questioned and released by police in the days just Schroeder’s body was found. First questioned by the F.B.I. for passing bad checks, Beardsmore was now “confined to a hospital for mental observation.” According to newspaper reports, the only evidence the police had against Wetling was Beardsmore’s statement. Nevertheless, on February 17, 1956, Wetling was indicted for murder.[46]

Four years to the day after the murder, jury selection was completed for the trial of Thomas Wetling. On September 23, Assistant District Attorney Harry Shrager asked for the death penalty for the “merciless killing” of Schroeder, saying, “You can fight a man and hit him but you don’t tie him up and gag him until he dies.”

During the trial, Beardsmore testified that he had loaned Wetling a suit on September 19, 1953, and later found the pants of the suit in a closet “covered with blood.” Beardsmore explained, “I asked Wetling about them and he said he had an argument with Schroeder, that he hit him several times and tied him up to prevent an outcry.” Wetling later told him, “It’s too bad the way things turned out, I didn’t mean to kill him.”[47]

Detective Sergeant John McBride testified that when Wetling was questioned in Newport, he claimed, “I don’t know nothing about nothing.” When shown photographs of the scene of the murder and Schroeder’s beaten body, McBride testified that Wetling “turned white, sweated and shook like a leaf for three minutes.”[48]

Taking the stand, Wetling denied that he had ever met or known Schroeder. He also denied ever telling Beardsmore he had murdered Schroeder. After deliberating for only twenty minutes, the jury of five men and seven women declared Wetling not guilty of the murder.[49] Shortly after he was acquitted, Wetling disappeared from Philadelphia, leaving behind a wife and two young children.

On October 6, 1958, Donald Britton murdered Thomas Wetling in Hollywood Hills, California. Partners in a business run out of Britton’s home that sold detective correspondence courses and detective equipment, Wetling had lived with Britton until six weeks before his murder. When Wetling returned to Britton’s home on the day of his murder, an argument over the division of profits and ownership of the business ensued and Britton, who had also paid for Wetling to be trained as an electronics technician, shot him five times. Britton had appeared as a character witness for Wetling during the Schroeder murder trial.[50]

In April of 1960, James Beardsmore was arrested for credit card fraud in Pittsburg. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported Beardsmore “had a cultivated taste for good clothes, good liquors, good food and such famed hotels as the Waldorf-Astoria and the Hilton.” The report said while Beardsmore claimed the closest thing he had to a permanent address was Pittsburgh’s Golden Hilton, one detective thought “Beardsmore may have a different and much more permanent address after the FBI gets through following his trail of carte blanche high living on credit through several states.”[51]

No one was ever convicted for the murder of Elmer A. Schroeder, the first American-born, and gay, president of U.S. Soccer.

The YouTube true crime channel The Crime Reel made two excellent videos on Schroeder’s murder and life based on this essay several years after its publication:

An earlier version of this article first appeared at the Philly Soccer Page on July 26, 2017.

Endnotes

[1] “Hunt Friend In Slaying of Attorney,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 22, 1953, 1,16; “Cops Hunt Friend in Slaying of Phila. Lawyer,” The Courier-Post, September 22, 1953, 1,5.

[2] Marc Stein, City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004), 117-120.

[3] Elwood Baher Cunningham, ed., The Record of the Class of Nineteen hundred and Twenty (1920), 102; “Additional Faculty Appointments Listed,” The Pennsylvanian, October 2, 1928, 1-2; Cops Hunt Friend in Slaying of Phila. Lawyer,” Courier-Post, September 22, 1953, 1,5.

[4] Levi Wilcox, “With the Soccermen,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 8, 1925, 26.

[5] Levi Wilcox, “New England Junior Champions Will Come Here for Interstate Soccer Honors,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25, 1926, 19.

[6] Levi Wilcox, “Kicks from the Corner,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 10, 1927, 27; Levi Wilcox, “Soccer Progressing at Lighthouse,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 26, 1927, 12.

[7] “Boys’ Friends Honor 3 Philadelphians,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 2, 1923, 2.

[8] Levi Wilcox, “Stewart Elected Soccer President,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 13, 1925, 21.

[9] Harry H. Fairfield, “Bomb Sprung in Election of Armstrong,” The Pittsburgh Press, June 12, 1926, 31; “Valley Soccer League Closes with Banquet,” The Morning Call, June 8, 1929, 18; Wilcox, Philadelphia Inquirer, October 15, 1929, 21.

[10] Levi Wilcox, “Benny M’Laughlin, Former Fleisher Star, To Quit; Injury Forces Retirement,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 4, 1928, 23.

[11] “Protest Victory of Portugal F.C.,” The Morning Call, June 5, 1929, 23; Levi Wilcox, “Blamphin Will Again Lead Eastern District State Soccer Magnates,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 15, 1929, 21; Levi Wilcox, “Kicks from the Corner,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 24, 1929, 15.

[12] “Schroeder Named Olympic Manager,” The Morning Call, April 20, 1928, 34; Harry H. Fairfield, “Soccer Hope is Killed,” The Pittsburgh Press, April 22, 1928, Sports Section 6.

[13] Levi Wilcox, “Olympic Selection Creates Dissension,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 30, 1928, 18.

[14] Elmer A. Schroeder, “Report of Manager, Soccer Team,” American Olympic Committee Report: Ninth Olympic Games, Amsterdam, Holland, 1928, (New York: American Olympic Committee, 1928), 271-282.

[15] Harry H. Fairfield, “Soccer Session Placid,” The Pittsburgh Press, July 1, 1928, 39. Including the loss to Argentina, the 1928 U.S. Olympic team compiled a record on one win, five losses, and three draws in Europe. In addition to the draws against Ajax on May 24 and 26, and the loss against Argentina on May 29, the U.S. lost 3-2 to the Netherlands in a friendly on June 1 before defeating Werder Bremen 3-2 on June 6. On June 10, the US lost 4-3 to Altona in Hamburg before drawing 3-3 in Warsaw to Poland on June 11. The arduous schedule and injuries resulted in a 6-0 loss to Lodz on June 12, and a 7-0 loss to Poznan on June 13. See Schroeder, 271-282.

[16] “World’s Soccer Tourney Opens in South America,” The Morning Call, July 12, 1930, 16.

[17] “Police Clear Friend of Slain Lawyer,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 23, 1953, 1, 40.

[18] “Papers Studied in Slaying,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25, 1953, 22; “Police Checking Phone Calls in Lawyer Slaying,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 26, 1953, 9.

[19] “Convict Is Top Suspect In Slaying of Attorney,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 11, 1953, B6; “Seek Convict in Murder of Schroeder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 10, 1953, 1, 10; James Lee, “Ten Top FBI Cases — No. 8,” The Daily Times (New Philadelphia, Ohio), June 3, 1955, 6.

[20] “Philadelphia Murder Fugitive Placed in FBI’s ‘Top 10,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 2, 1954, 10; “FBI Captures Suspect in Schroeder Murder; On ‘Most Wanted’ List,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 4, 1954, 1.

[21] “3 Oswego Jail Escapees Hunted Near Welch, Okla.,” Joplin Globe, March 31, 1954, 1.

[22] “Tires of Fugitive Role,” Kansas City Times, April 7, 1954, 8 (40); “Basil Beck, 27 Years,” Kansas City Times, April 10, 1954, 1 (45).

[23] “Torso Timetable,” Delaware County Times, May 1, 1954, 2; Torso Slayer Identifies Former Seaman as Victim,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 3, 1954, 1, 8.

[24] “Quiz Schroeder Suspect in Navy After New Tip,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 24, 1955, 13.

[25] “Elmer A. Schroeder Heads Big Soccer Body,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 19, 1932, 24.

[26] “Big League Soccer for Philadelphia; Declares Schroeder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 20, 1932, 30.

[27] “Soccer Boomed This Year,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 25, 1932, 4S.

[28] “Soccer Players Must Pay,” The Pittsburgh Press, June 14, 1933, 26.

[29] “Stars of Stix and Pawtucket are Invited to Final Tryouts,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 13, 1934, 18.

[30] Ed Farnsworth, “The US and the 1934 World Cup,” The Philly Soccer Page. Retrieved July 20, 2017 http://www.phillysoccerpage.net/2014/03/26/the-us-and-the-1934-world-cup/

[31] “St. Louis Soccer League Granted Direct Affiliation By Officials of the U.S.F.A.,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 14, 1934, 11.

[32] “Elmer A. Schroeder is Pro Soccer Czar,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 13, 1934, 12.

[33] Ed Farnsworth, “Philadelphia German Americans win the 1936 US Open Cup,” The Philly Soccer Page, retrieved July 20, 2017 http://www.phillysoccerpage.net/2014/09/03/philadelphia-german-americans-win-the-1936-us-open-cup/

[34] Harry Fairfield, “Illinois Man New Prexy of National Soccer Body,” The Pittsburgh Press, June 28, 1936, 17. Soccer was not included in the program of the 1932 Olympics, which was staged in Los Angeles. Many believed the US should not participate in the 1936 Olympics because the Games were being turned into a propaganda vehicle by the Nazis. David Wangerin writes Schroeder and then USFA president Joe Barriskill thought participation was “justifiable–so much so that Schroeder received a special award from the Reich in recognition of his efforts.” Wangerin does not provide further detail about the award and there is no mention of it in the International Olympic Committee or U.S. Olympic Committee reports on the Berlin Games. See “David Wangerin, Soccer in a Football World (London: WSC Books, 2006), 99-100. Jospeh Barriskill authored the soccer section of the 1936 U.S.O.C. report and he undoubtedly goes to great, even embarrassing, lengths to defend U.S. participation in the Games. He writes, “[D]elegates of the United States Football Association… comprehended fully the real purposes and values of the Olympic Games, and they refused to be misguided, as were undoubtedly many leaders of other sports, by propaganda which was circulated lavishly — designed to defeat American participation” in the Nazi-hosted Games. He further asserts “a maximum share of the propaganda which was circulated against the Games being held in Germany in an effort to prevent American participation was not based on facts; that the athletes were well received abroad and that no attempt was made to influence them in favor of German political theories or to restrict them in religious worship, in a manner in which they were accustomed to worship God at home, regardless of creed.” Joseph J. Barriskill, “Report of Chairman of Soccer Committee,” in Report of the American Olympic Committee, ed. Frederick W. Rubien (New York, American Olympic Committee, 1937), 252-256. I have been unable to find mention of Schroeder’s political beliefs in newspaper reports of the day. But Philadelphia-area newspapers reported that on December 13, 1941 — six days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and two days after Nazi Germany declared war on the U.S. — Schroeder had enlisted in the U.S. Navy at the Boston Navy Yard. A report the following summer said Schroeder was being granted an “Army intelligence commission following recovery from a slight operation.” See “Schroeder Enlists In U.S. Navy,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, December 15, 1941, 25; “Elmer Schroeder Enlists in Navy,” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, December 15, 1941, 25; William Graham, “Sanford Outfit Not To Field Soccer Team,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 31, 1942, 11.

[35] “Yankees Boot Squad Loses Hard Fought Tilt to Italy, 1-0,” The Reading Times, August 4, 1936, 12. After an Italian player injured Philadelphia’s Bill Fiedler, the German referee tried to eject the Italian player three times “but finally gave up” after “half dozen Italian players swarmed over the referee, pinning his hands to his side and clamping hands over his mouth.”

[36] “German-American Eleven of Philly to Boot for Pay,” The Reading Times, October 8, 1936, 16.

[37] “Davies to Pilot Amerck Booters,” The Reading Times, July 1, 1937, 14.

[38] “Reading Man on Soccer Team Going to Mexico,” The Morning Call, August 27, 1937, 30.

[39] Soccer Moguls Refs Still Feud,” The Reading Times, October 23, 1937, 20.

[40] William Graham, “Schroeder is Named A.L. Soccer Head,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 19, 1939, 15; “Cuban Booters In Game Tonight,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 3, 1941, 28.

[41] “Philadelphia Team Seeks Berth in Loop,” Mount Carmel Item, August 31, 1939, 9.

[42] Harrisburg Telegraph, April 8, 1944, 9.

[43] Phila. Americans Beat Phoenix in Soccer, 7-2,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8, 1947, 22; “Mike Majkowski To Pilot Americans,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 25, 1948, S8.

[44] Bill Graham, “Soccer Names 21 Old-Timers To Hall of Fame,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 28, 1951, 21.

[45] “Sailor Accused in Slaying Of Noted Soccer Official in ’53,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 28, 1955, 31.

[46] “Schroeder Case Suspect Quizzed,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 30, 1955, 8B; Action Delayed in Schroeder Murder Case, Philadelphia Inquirer, November 1, 1955, 17. “Sailor Suspect Denied Bail in Schroeder Case,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 3, 1955, 25; “Bail Allowed Suspect in Schroeder Murder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 22, 1955, 2; “Sailor Indicted in Attorney Death,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 18, 1956, 13.

[47] “Prosecution Demands Wetling Be Sentenced To Death for Murder,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 24, 1957, 31.

[48] “State Rests Case At Wetling Trial In 1953 Slaying,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25, 1957, 43.

[49] “Ex-Sailor Acquitted in Schroeder Slaying,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 26, 1957, 27.

[50] “Detective School Owner Slays Former Partner,” Los Angeles Times, October 7, 1958, 5; “Former Sailor Freed In W. Phila. Slaying Shot, Killed in West,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 17, 1958, 20.

[51] “He Lives High On the Cuff,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 26, 1960, 5.