Our series on soccer’s origins in Philadelphia continues with a look at football in and around the city in the first half of the 19th century in the leadup to the codification of Laws of the Game of association football in 1863.

By the close of the eighteenth century and beginning of the nineteenth century, the playing of football in the United States began to be associated with schools and colleges. This had been the case in Britain for a number of centuries. As early as 1303 an English footballer had been attacked and killed by Irish students at Oxford. By the mid-nineteenth century, various English public schools had their own forms of football and graduates of these schools would be at the forefront of the formation of the FA and the codification of the rules of association football and rugby.

School-based football and the lead-up to the codification of the Laws of the Game

Melvin I. Smith recounts in Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball that school-based football games were present at Roxbury Latin School near Boston by 1768, with accounts of football being played at Yale by 1793, and at Harvard and Dartmouth by around 1800.

Thus far, I have been unable to locate references to school-based football in Philadelphia before the 1840s. But, an account by an unnamed British visitor to the US first published in the Edinburgh Review and excerpted in Philadelphia’s National Gazette and Literary Register in October of 1824 read,

One thing that I could not help remarking with regard to Americans in general, is the total want of all those games and sports that obtained for our country the appellation of “Merry England”…In America I never saw even the school-boys play at any game whatever. Cricket, foot-ball, quoits, &c. appear to be utterly unknown. (Emphasis in the original.)

The account is prefaced with a brief introduction from the editor of the National Gazette that ends, “It is indeed a just specimen of the general accuracy of those tourists.” In other words, simply because the visitor from Britain did not see school-boys playing games of football, it does not follow that such games were “utterly unknown.” The mocking tone suggests that readers of the account would find the suggestion that there was no football being played to be as laughable then as it is difficult now for historians to find contemporary accounts of such games.

That football was being played in Philadelphia is further evidenced by a letter printed in the Public Ledger in August 1838 that complains of “legions of disorderly boys” disrupting the peace of citizens wishing to use Franklin Square, located between Sixth and Seventh Streets at Race Street.

We would encourage athletic exercise among boys, as necessary to health and vigor of constitution; but we consider a place crowded by women and little girls, and men, seeking the calm recreation of an evening walk around a beautiful fountain, no place for football, the horse race or war dance.

As far as I’m aware, this is the first account naming a location where football was played in Philadelphia.

An edition of the North American and Daily Advertiser from November 1842 reprinted an extract from the October edition of the British literary magazine Bentley’s Miscellany that gives another sense of how pervasive football games were.

Zeal.–Men’s seal for religion is much of the same kind as that which they shew for a foot-ball, whenever it is contested for, every one is ready to venture their lives and limbs in the dispute; but when that is once at an end, it is no more thought on, but seeps in oblivion, buried in rubbish, which no one thinks it worth his pains to rake into, much less remove.

In this we get the sense that football is a ubiquitous game, one in which “every one is ready to venture their lives and limbs in the dispute,” but not one that continually occupies the mind, much less the effort of recording instances of play. It is a familiar game, but not a sport as we would understand the word.

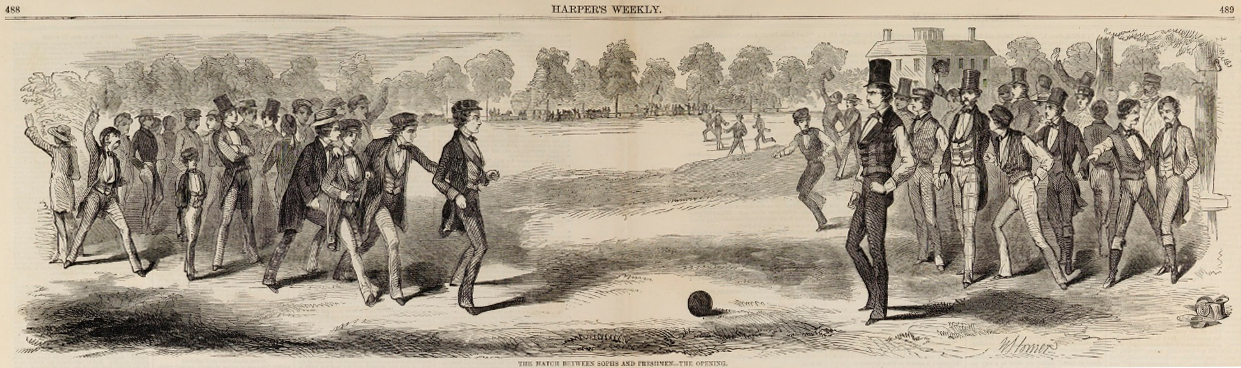

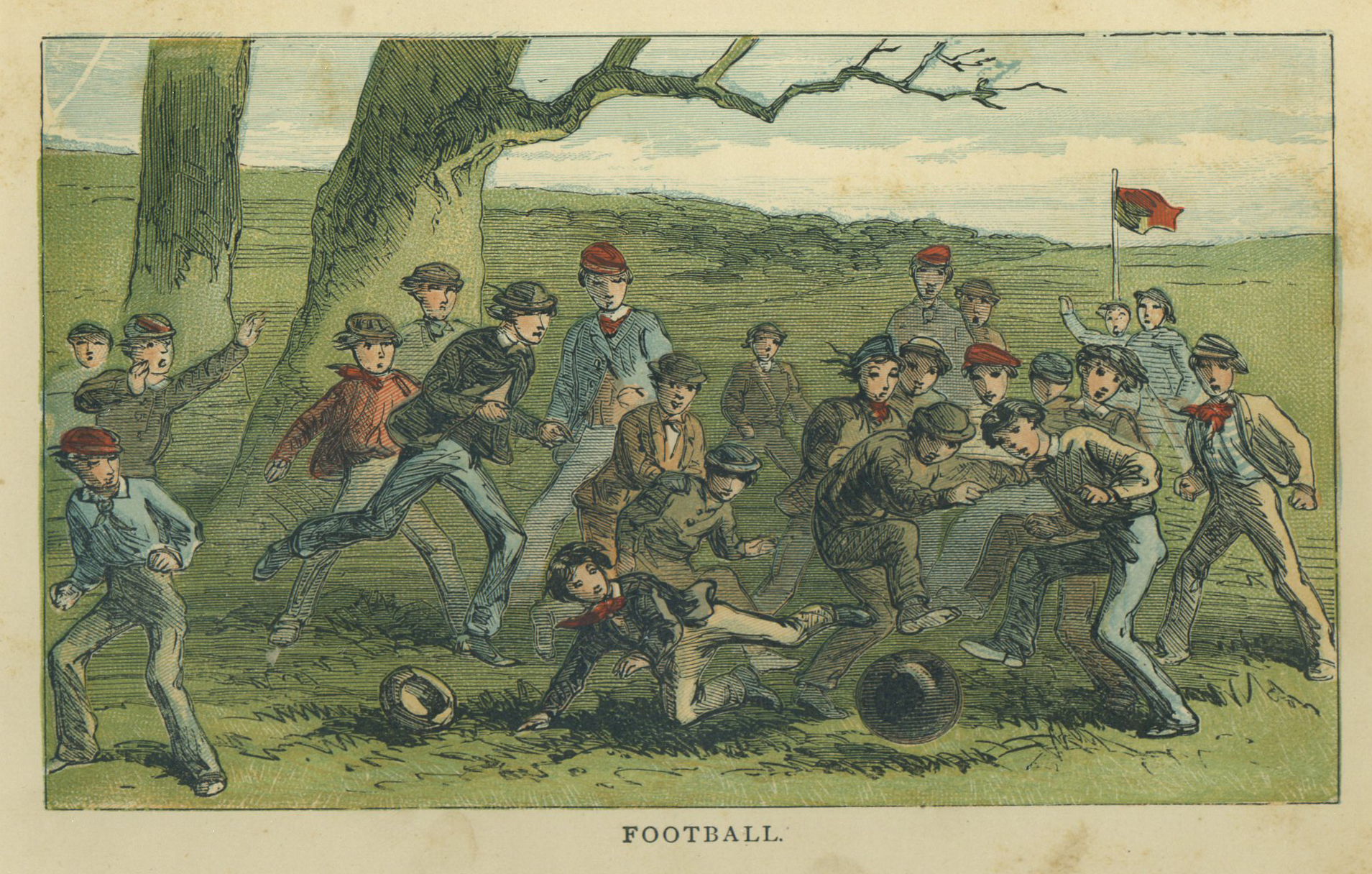

Nevertheless, there are references to school-based football games in Philadelphia in the 1840s. Smith describes students at the University of Pennsylvania, then located at Ninth and Market streets, playing football against local high school students in 1844, adding that the university’s Junior Cricket Club “might have played a game or two of foot ball” against the Philadelphia High School Cricket Club during the winter of 1845-46. Just outside of Philadelphia, football was being played at Haverford College by 1840 with annual contests between freshmen and sophomores occurring throughout the decade. An article reprinted in a November 1863 edition of the Christian Recorder, the newspaper of the African Methodist Episcopal Church published in Philadelphia, recounts “the beginning years” of Girard College — founded in 1833 and opened in 1848 — in which there were “huge games…of football.”

Princeton, known as the College of New Jersey until 1896, had been playing a form of the English game ballown since 1819, a game in which players were allowed to use their hands to bat a ball forward but not to carry it the ball, and had been playing a kicking form of football since the 1840s. In 1857, students there formed the first college football club in the US. The same year on Thanksgiving Day in Columbia, Pa. in Lancaster County, a town team played an unknown team in a game of football.

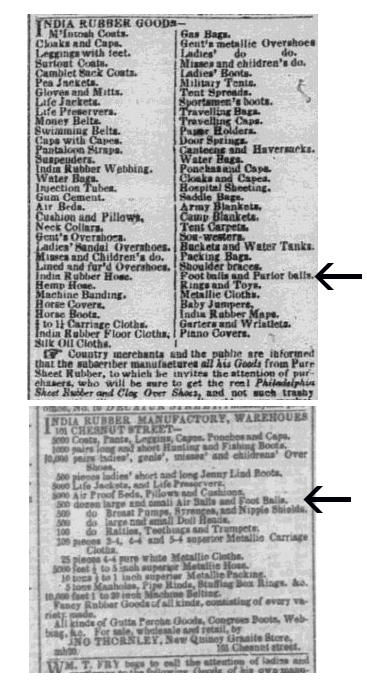

Although newspaper accounts of football being played in Philadelphia during this time are few, footballs were advertised for sale in at least one Philadelphia newspaper. In an edition of the North American and United States Gazette from March 1850, John Thornley advertises “Footballs and Parlour Balls” for sale. The listing describes, “Country merchants and the public are informed that the subscriber manufactures all his Goods from Pure Sheet Rubber” (emphasis in the original). In an edition of the North American and United States Gazette from May 1851, Thornley advertises the availability of “500 dozen large and small Air Balls and Foot Balls” for sale at his “New Quincy Granite Store” at 101 Chestnut Street. Smith notes that with the availability of India-rubber balls, “kicking or dribbling of the ball along the ground became the primary way to move the ball forward.”

Princeton had an India-rubber ball by 1858 and the first intercollegiate soccer-style football game may have occurred between Princeton and the Princeton Theological Seminary around this time. Smith relates that this new style of play “became so popular with students that the administration stopped it in late 1859” because it was “taking too much time and energy from school-work to continue.”

Back in Philadelphia, a Philadelphia Inquirer report from October 1858 on a City Council session notes discussion about the Pennsylvania Railroad Company-owned “Powelton grounds” on the west side of the Schuylkill River. The discussion was prompted by concerns over horse racing on the property, which had been leased by the Pennsylvania Railroad to a man “to graze his mules, and he has, it appears, turned it into a racing ground.” The report continues,

Mr. Cornman said the gentleman from the Thirteenth Ward had not alluded to all the desecration on the west side of the Schuylkill. He said that from an article which appears in an afternoon paper, a fine tribe of Tuscaroras are to be there to-morrow, have football, amusements, and riding on mustangs, &c.

The Tuscaroras are a Native American tribe that, before the arrival of Europeans, had settled in what would become North Carolina, migrating north to Pennsylvania and New York following the Tuscarora War (1711-1713). The Tuscarora was also a packet ship that was scheduled to embark from Philadelphia for Liverpool on Nov. 6, 1858, but the reference seems to apply to Native Americans, not the ship’s crew. As such, it is the only direct account that I have so far been able to find of America’s original footballing people playing the game in Philadelphia.

Football during the Civil War

The Civil War years saw a relative decline in the playing of football at colleges: faculty opposition to football as a distraction and the violent style of play had resulted in familiar bans and many students were away fighting in the war. But at Princeton, the kicking style of football that had become so popular with the advent of India-rubber balls that it was banned in 1859 resumed in the 1864-65 school year.

While the Civil War marks the germination of baseball, the sport that would captivate the country in the ensuing decades, soldiers certainly played football: an engraving in Harper’s Weekly from 1861 entitled “The First Maryland Regiment Playing Foot-Ball Before Evening Parade” shows what appears to be the kickoff of a game in which the opposing sides consist of scores of players. Visible at one end of the playing field are two cannons spaced apart that appear to mark one of the goals. (Click here to view the engraving.)

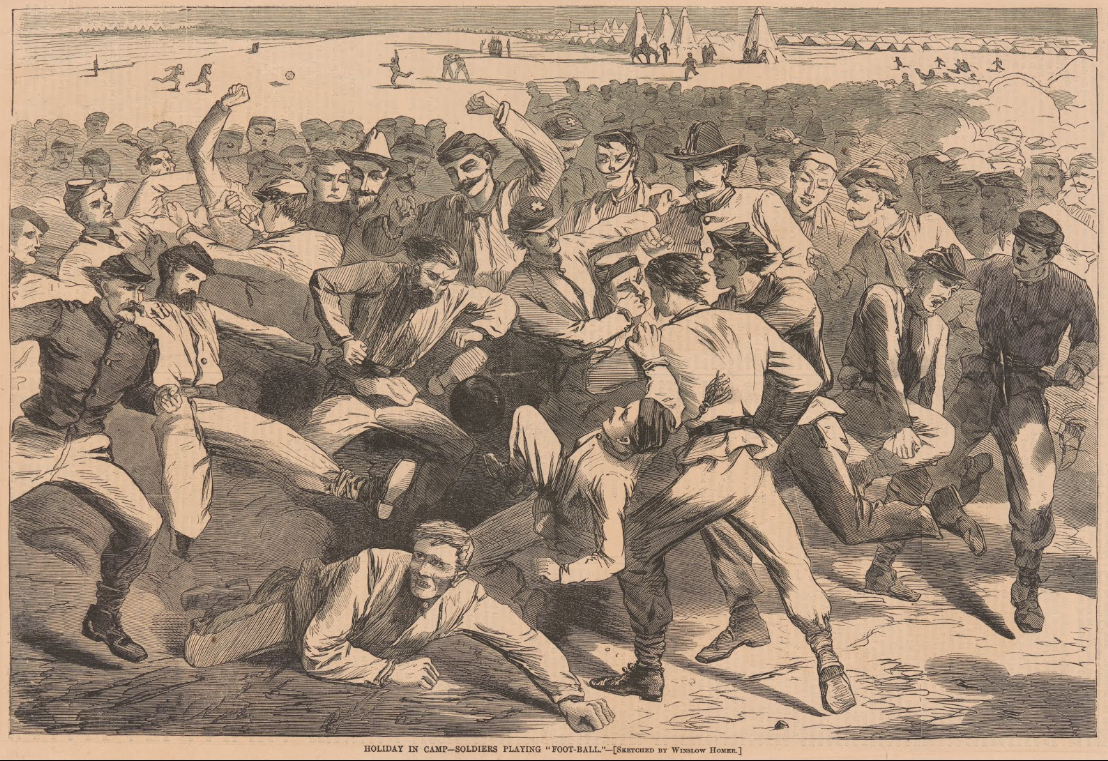

A scene that would have been familiar to a colonist landing in Philadelphia from Britain one hundred years before is the subject of a Winslow Homer illustration in Harper’s Weekly from July 1865. Entitled “Holiday in Camp — Soldiers playing ‘Football,’” it shows two opposing sides engaged in something more resembling a brawl – or what Smith referred to as “a gang-fight centered around a ball” when describing football at the close of the eighteenth century — than what we would think of as a game of soccer. Very small in the background of the engraving are three figures kicking a ball.

The British colonists who founded and settled Philadelphia encountered Native American tribes who had their own football games. But these native traditions had no impact on the football traditions the colonists brought with them. The forms of football played by the colonists would have followed the forms of play back home in Britain, with rules that may have allowed both handling and kicking of the ball, not to mention potentially violent play. References to the playing of football are often indirect, whether through football as a metaphor, or through football as a disruptor of the public peace, as evidenced in attempts to ban the game through the law, or in newspaper accounts that refer to the playing of football as a public nuisance. Accounts of football games themselves are few. The playing of football was likely spontaneous and informal, rather than an organized contest in itself or to celebrate secular or religious holidays, a trend that would remain until the development of school-based forms of football led first to games within a particular school, and then games against other schools. Furthering the ongoing development of various school-based forms of football was the development of a new technology that created better footballs and so encouraged the trend toward styles of play that favored kicking over handling of the ball.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, momentum was gathering for the codification of the Laws of the Game, setting in motion a version of football that would develop into the most popular and widely played team sport the world has ever known.