Looking back now from a time in which it is the most popular sport in the world to the creation of the original Laws of the Game of association football in December of 1863, it’s easy to assume that soccer must have spread, fully formed, like wildfire throughout the world.

But the growth of association football, at least as embodied in the Football Association, was initially slow. Rival codes of play and rival soccer-style football associations meant that the purpose of the FA, namely the creation of a uniform set of rules of play in order to ease the arrangement of games, was slow to be realized. This process began to pick up speed with the staging of the first Football Association Challenge Cup tournament, known today as the FA Cup, in 1871-72, and when the FA Laws of the Game and the Sheffield Rules were unified in 1877. But while the original Laws of the Game are acknowledged as the founding moment of soccer, the game itself would evolve over the next several decades before it began to truly resemble the game that is played today.

For example, the original 1863 rules allowed handling of the ball to make a fair catch, although picking up the ball, carrying the ball, and throwing the ball were forbidden. Handling of the ball was eliminated in 1866, the same year that the forward pass was first allowed through the introduction of the offside rule, although a minimum of three opponents had to be between the player receiving the ball and the goal. Goalkeepers, first named as a specific position in 1871, were allowed to handle the ball anywhere in their own half of the field until 1912 when they were finally restricted to handling the ball within their own penalty area. The goal itself was originally simply two posts in the ground; the introduction of a tape stretched across the top of the posts soon followed but crossbars weren’t introduced until 1882. Nets weren’t required until 1892. Goal kicks were introduced for the first time in 1869. Corner kicks came in 1872.

The dimensions of the field of play in the 1863 rules allowed for a pitch that could be as long as 200 yards, and one hundred yards wide. Originally, the boundaries of the field of play were marked only by flags; lines marking the field of play and the halfway line weren’t introduced until 1882. A twelve-yard penalty area was introduced in 1887, the same year the center circle appeared, with penalty kicks allowed beginning in 1891; the 18-yard penalty area followed in 1902. Match officials, originally two umpires on the sidelines consisting of one representative from each team, were introduced in 1874. A third official, who kept time and to whom the two umpires “referred” when they couldn’t agree on a call, soon followed. The “referee” appears in the Laws of the Game for the first time in 1881, but the referee as the ultimate arbiter of the game wasn’t formalized until 1891. Nevertheless, it was up to team captains to alert the referee to infringements until 1898, when the referee was finally empowered to identify infringements on his own and the two umpires became neutral linesmen. Substitutes weren’t formally allowed until 1958. Back-passes to the goalkeeper weren’t banned until 1992.

It follows that the evolution of the rules of play was accompanied by an evolution in the tactics of how the game was played. David Goldblatt writes in The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football (2006),

Most teams fielded two backs, one half-back and seven forwards. Although the backs would often hoof the ball far up the field, most of the time the ball moved at the feet of individuals dribbling the ball towards the opponent’s goal. Passing was only considered as a last resort and indicated failure, even dishonour. During the 1877 England-Scotland game the Hon. Alfred Lyttleton, when challenged about his failure to pass the ball, remarked to his team-mate but social inferior Bill Mosforth, “I am playing purely for my own pleasure, Sir!” High crosses and heading of the ball were also absent from the players’ repertoire.

As Goldblatt describes, “the formation and practice of teams was a long way from the style of the modern game.” (For more on the tactics of early soccer games in Philadelphia, see 2-3-5 in the 215: Tactics in the early days of Philadelphia soccer.)

It is difficult to know how long it took for the rules laid down by the FA in 1863 to make their way to Philadelphia. A book review in the Philadelphia Inquirer from November 1864 describes The American Boy’s Book of Sports and Games as “a right royal contribution to Young America” containing “more than six hundred engravings, illustrating every sport.” However, the game of “Foot-ball” is found in the book under the heading “The Laws of Foot-Ball, As Played at Rugby.” So, less than a year after the publication of the Laws of the Game, the book describes only one form of football — and a school-based one, at that — despite this being but one of several organized football styles being played in Britain by this time.

As Melvin I. Smith describes in Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball (2008), that the Rugby School’s football rules — which should not be confused with the game of Rugby that was eventually formalized in 1871 with the establishment of the Rugby Football Union — rose to the forefront may be related to the popularity of a piece of literature, Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown’s School Days, which was first published in London in 1857. Indeed, on November 18, 1869, the Germantown Cricket Club and the Young America Cricket Club played a game, the rules of which the Philadelphia Inquirer reported were “adopted chiefly from those of Rugby School, England,” on the grounds of the Germantown Cricket Club. The Thanksgiving Day game, which featured 22 players per side “in their tidy dress and lightly colored sashes (worn to distinguish the sides)”, was played for more than two hours before Germantown finally scored the only goal.

First published account of a game of soccer-style football in Philadelphia after the 1863 Laws of the Game?

In the 1864-65 school year, students at Princeton University began to play again the kicking style of football that had been banned by the school’s administrators in 1859. By 1865, students at Haverford were playing scrub football, a form of football that allowed handling of the ball and, from the description of the game in A History of Haverford College for the First Sixty Years of Its Existence (1892) seems to have largely been played in the free time between classes. Whether the rules of the Haverford game were influenced by the rules of association football as laid down in 1863 is unclear. However, that handling the ball was allowed in Haverford’s scrub football does not necessarily mean that it wasn’t influenced by the original Laws of the Game.

In 1866, Beadle and Co. of New York published a set of rules in Cricket and Foot-ball of 1866 for both “Association Foot Ball” and the “Handling Game.” By 1867 the “Princeton Rules” had been developed and were based in part on the 1863 FA code. The Princeton Rules allowed for teams consisting of twenty-five players. While this may seem odd, the original Laws of the Game say nothing of the number of players each side could have on the field of play. As with the 1863 rules, under the Princeton Rules, players could take a free kick after catching the ball — on the fly or after one bounce — but could not carry or throw the ball. Games between Princeton and the Princeton Theological Seminary under the Princeton Rules followed. On November 6, 1869, Princeton played Rutgers in a kicking-style game of football with rules based on Rutgers’ versions of the 1863 rules. Rutgers won. Interestingly, this game is often referred to as the birth of American college gridiron football, although the ball that was used for the match is held by the National Soccer Hall of Fame, not the College Football Hall of Fame. On November 13, the teams met again in a game played under Princeton’s rules of the game. Princeton won.

While the general trend of schools becoming the first to play football according to the 1863 FA code might lead one to assume that the University of Pennsylvania would be central in the first published account of a kicking-style football game in Philadelphia, that honor may actually go to an ethnic organization, the Philadelphia Irish Nationalists.

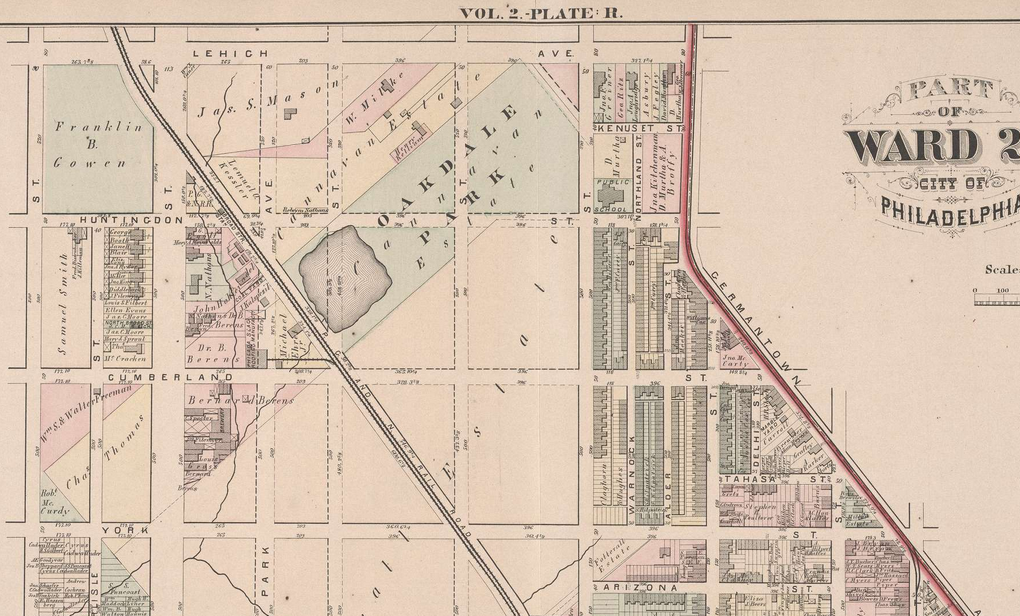

In Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball, Smith records a game taking place in June of 1870 between the Irish Nationalists and “Unknown team,” but he is unable to provide a specific date or a score for the game, and I have been unable to find a reference to that game in a database of Philadelphia newspapers. But on June 26, 1871, the Irish Nationalists held their second annual picnic at Oakdale Park, which was located between West Lehigh and Cumberland Avenues, and Thirteenth and Eleventh Streets. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported the next day,

A large number of persons were in attendance. The sports commenced shortly after two o’clock with a game of football. The competing clubs represented New York and Philadelphia, and after some hard kicking, the game was decided by the judge, Mr. James Carr, in favor of the New York Boys.

A report in the Public Ledger notes “considerable interest was manifested in the various sports prepared for the occasion,” and provides some more detail about the game.

The principal game was that of football, between the New York and Philadelphia Clubs, for a prize of $250, which was won by the former organization, after a contest of an hour and a half. There were twenty-five men in each club, and the contest was an exciting one.

I have been unable to locate a report on the Irish Nationalist’s third annual picnic in 1872, but we can probably assume that football was played then too, given “the considerable interest” in the 1871 game.

When the Irish Nationalists held their fourth annual games at Oakdale Park on August 27, 1873, “in the presence of a very large crowd of spectators,” football was again played. The Inquirer reported the next day,

The programme opened with a game of foot ball between the Knights the Red Branch, of Wilmington, Del, and the Irish Nationalists, of this city. The contest was warm, and there was some excellent “kicking” done, especially by Messrs James Ryan, John Nichol, Mr. McEntee and J. Donohue. The game was won by the Nationalists, who, with their victory, secured the prize of $100.

Were these the first association football games played in Philadelphia? There is reason for some doubt. Was the game the Irish Nationalists played some version of caid, the Irish folk football precursor to Gaelic Football, which was first codified in 1887? This is possible, but no mention is made of handling the ball — or, more importantly, of carrying the ball — in either of the three accounts of the games, while kicking is specifically referenced. So, assuming the game played was not caid, while we have no score for either the 1871 or the 1873 game, the first local team to play what would soon be referred to as “the English game” in Philadelphia newspaper accounts may have been an Irish club.

But, there is a further reason for doubt. A Philadelphia Inquirer column from December 1919 reports,

For the benefit of those who take a delight in tabulating records, Mr. Wainman, who is recognized as the “father” of soccer in this city, announces that the first soccer match under proper rules was played in this city on March 19, 1881. A rubber ball was used on that occasion.

Unfortunately, the teams that played this game, and the final result, are not described. Smith does not record the match and I have been unable so far to locate any records of it other than the mention in the 1919 Philadelphia Inquirer article.

In the event, it is interesting to note that the Irish Nationalist games took place against teams from other cities. Aside from being noteworthy in itself, this suggests two things. First, just as with the players who formed the Philadelphia side, a kicking, non-ball-carrying-style of football was being played enough in other cities that teams could be fielded against Philadelphia sides. Second, we can infer that, if these are the first newspaper accounts of a 1863 Laws of the Game influenced-style of football in Philadelphia, it is likely that other games were taking place. There was interest in the game — a marquee event of the picnics — which suggests that spectators had some personal knowledge of the game. Also, the games are described as “exciting” and “warm,” with “some excellent ‘kicking’ done,” which further suggest the players had at least some level of skill and familiarity with the game themselves.

Youth football in Philadelphia after the 1863 code

Smith notes that in the 1872-73 school year, “The Delaware Institute of Wilmington,” a high school, had a team playing by association football rules, “but no records of games played can be found.” Were student players a part of the Knights of the Red Branch team that lost to the Philadelphia Irish Nationalists? We do not know, but the existence of a Wilmington high school team does suggest a growing local awareness of football played according to the 1863 code.

A report in the Philadelphia Inquirer from August 1872 of the “Fourth Children’s Free Excursion” to Fairmount Park, an annual event organized by Philadelphia philanthropists for the benefit of “children of the poor,” highlights the playing of football by young Philadelphians: “A great many consumed a portion of the time in playing football and baseball.” A letter to the Philadelphia Inquirer in March 1873 from “A member of the senior class of the Lincoln School, Fifteenth Ward,” takes issue with three previous letters printed in the paper that he believes unfairly characterized his school. On the question of whether the school is adequately providing for the physical health of its students, he writes, “Our ages are from 14 to 16 years, and if you can find any twenty-five boys, of our ages, who have as fine a physical development, we are willing to try our skill with them at a game of football. If they wish to match their mental faculties against ours, we will give them a trial at mental arithmetic and algebra.” Under what rules such a contest would have been played is not described.

In A History of Athletics of the Germantown Academy (1910), Fred C. Vail writes, “Sometime in the ’70s the Academy lost a game of Association Football to Bromhead’s English Team, and from then until 1900 there was no ‘soccer’ at Germantown.” Vail, who graduated from Germantown Academy in 1900, does not record a specific date for the game. In Early American & Canadian ‘Football’ (2003), Melvin I. Smith records the game against “the touring Bromhead Football Club of England” as taking place in 1877 but in Evolvements of Early American Foot Ball (2008) he describes that Germantown Academy “possibly lost to the Bromhead Team of England in the spring of 1877.” My own correspondence with The National Football Museum in England has uncovered no records of a “touring” Bromhead club, although they were very interested to hear of the account. (For a discussion of the question of the Bromhead team, which I suggest may have been organized by George Bromhead, an English cricketer who settled in Philadelphia, see Philly’s first international.)

Outside of Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Military Academy, known today as Widener University, defeated the Chester Town team on November 3, 1877, by the incredible score of 12-11. In Pennsylvania Military College — The Story of One Hundred Years (1921) Henry J. Buxton quotes R. Kelso Carter: “Football began at Chester, at first very crudely, with any old rules-scramble, kick and scratch.” Smith records that Chester High School played soccer-style football in 1877 but he is unclear if the Chester High School team and the Chester Town team are the same, although this is likely the case. Both the Pennsylvania Military Academy and Chester High School switched to rugby-style “carrying” football in 1878.

Trenton High School, now Trenton Central High School, played two games against amateur sides in December 1877 before beginning to play rugby-style football. They defeated Trenton Independents 2-0 on December 1, 1877, at Liberty Grounds, then defeated the Trenton International team 8-0 on December 27.

Philadelphia-area universities continued to experiment with kicking-style football influenced by the 1863 code during this period. But, as we shall see, they soon abandoned such play in favor of the handling-, carrying-style of play that would develop into American football.

A version of this article first appeared at the Philly Soccer Page on November 24, 2014.