Rival college football codes

Perhaps more important than problems arising from rival codes in the evolution of soccer was the division between supporters of the “dribbling game,” soccer-style association football, and supporters of the “handling game,” or what would become rugby football. This conflict was evident during the founding of England’s FA when rugby football-supporting clubs who, in addition to favoring the handling of the ball, also wanted hacking — or being able to kick an opponent in the leg — to be allowed, left the organization, eventually forming the Rugby Football Union in 1871. The “handling game” was at first more popular. Matthew Taylor writes in The Association Game: A History of British Football (2008) that in 1873, 122 clubs played a version of association football in Britain while 130 played rugby.

As we have seen, the original 1863 Laws of the Game allowed for the handling of the ball to make a fair catch, although picking up the ball, carrying the ball, or throwing the ball were forbidden. While this was eliminated from the Laws of the Game in 1866, American universities were creating their own codes for football that, along with their own local traditions, continued to be based on the 1863 rules and so allowed for handling the ball.

An account in the Rutgers student newspaper The Targum from November 1869 of the series of games between Rutgers and Princeton that took place that month helps to illustrate this.

Princeton had the most muscle, but didn’t kick very well, and wanted organization. They evidently didn’t like to kick the ball on the ground. Our men, on the other hand, though comparatively weak, ran well, and kicked well throughout…

The style of play differs, materially, in the two Colleges. A fly, or first bound catch, entitles to a “free kick,” a la Princeton. We bat with hands, feet, head, sideways, backwards, any way to get the ball along. We must say that we think our style much more exciting, and more as Foot Ball should be.

While Princeton can be said to have been playing “soccer-style” football in 1869 because the Princeton Rules were based on the 1863 Laws of the Game, they were not playing football according to the revised Laws of the Game. In contrast, Rutgers’ rules resemble those found in the original Sheffield Rules of 1858 which, in addition to allowing the “fair catch,” also said, “The ball may be pushed or hit with the hand, but holding the ball except in the case of a free kick is altogether disallowed.” By 1860, however, this was replaced with, “Holding the ball (except in the case of a free kick) or knocking or pushing it on is altogether disallowed.” The various codes followed by leading US colleges were slow to reflect revisions to the Laws of the Game in Britain.

The existence of differing football codes was an obvious problem and on October 19, 1873, representatives from Princeton, Rutgers, Columbia, and Yale met in New York to devise a uniform set of rules. Mark F. Bernstein writes in Football: The Ivy League Origins of an American Obsession (2001) of the 1873 rules, “The game they agreed upon still very much resembled soccer; no throwing or carrying the ball was permitted. Teams were to have twenty men to a side, although Yale argued for eleven on the theory that it might be easier to gain faculty approval for fewer men to travel to away games.” Melvin I. Smith writes in the November 2010 edition of the College Football Historical Society newsletter that “twelve common kicking game rules” made up the 1873 rules. He adds that, after the 1863 Laws of the Game, and the formation of Scotland’s Football Association in March 1873, the 1873 Princeton-led rules meant “America was the third country to consolidate their kicking game rules,” adding, “These rules were also taken from the 1863 English code.”

The rules that stamped the game as something resembling soccer were rules No. 5 and No. 7:

5. No player shall throw or carry the ball. Any violation of this regulation shall constitute a foul, and the player so offending shall throw the ball perpendicularly into the air to a height of at least 12 feet and the ball shall not be in play until it has touched the ground.

7. No tripping shall be allowed, nor shall any player use his hands to hold or push an adversary.

While Princeton, Rutgers, Columbia, and Yale were agreeing to move their football in the direction of the “dribbling game,” what proved most important was that Harvard, which favored the ‘handling” game, was, despite an invitation to join the meeting, not in attendance.

From the late 1850s, a rugby-style “handling” football had been played in the Boston area with intra-class games played at Harvard from at least 1858. In Boston, play was not limited to Harvard: by 1862, the Oneida Football Club had been formed at the Dixwell Latin School (see Roger Allaway’s Were the Oneidas playing soccer or not? (2001) for more on the importance of the club). But the “Boston Game” would soon be associated with Harvard. And without the participation of Harvard, the leading college in the United States, any attempt to create a uniform set of rules to govern how intercollegiate football would be played was doomed to failure.

Penn lags behind US college-based football development after the 1863 Laws of the Game

The University of Pennsylvania at this time was a small and sleepy institution compared to the one it is today. Indeed, a column in Penn’s University Magazine from May 1876 observed, “our University is hardly known outside of Pennsylvania and New Jersey,” and wondered “how is it that the University of Pennsylvania takes her rank, with shame be it said, as a third-class University” behind the likes of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Columbia?

In terms of football, location seems to have been a significant obstacle. During the first half of the nineteenth century, Penn was located at Ninth and Market Streets, only moving across the Schuylkill to its present West Philadelphia location at the beginning of the 1870s. Thus, as the football boom that was beginning at other east coast universities in the late 1860s, Penn’s downtown location meant that easy access to open playing spaces was limited. Enrollment was also small — a mere 92 students at the start of 1869 according to numbers in the April 1876 edition of University Magazine — so the numbers necessary to sustain participation in organized football were lacking. Perhaps the biggest problem was that, at the time, the university had no on-campus housing for its students. Without students gathered together after class hours, it was difficult to create the momentum required to get new sport initiatives off the ground.

And so, the May 1876 edition of University Magazine reported of attempts to organize a crew to represent Penn at in the intercollegiate Rowing Association,

But unsuccessful they have been, as also have our attempts to organize representative base ball nines and foot ball twenties, and until our joining the Intercollegiate Athletic Association, we have, though standing high in point of numbers among American colleges, and representing as an institution of learning the second city of the Union, taken part in nothing in common with the other colleges of this country.

Even membership in the Intercollegiate Athletic Association (IAA) didn’t necessarily facilitate matters if the administration wasn’t supportive of the students’ athletic association efforts to join in the growing intercollegiate sport movement. The University Magazine recounted in May 1876 that “when the Athletic Association wished to send delegates to the inter-collegiate convention, the delegates could get no leave of absence from the authorities.” This was compounded by the fact that the IAA apparently didn’t think highly enough of Penn to keep them informed about important matters such as a scheduling change. Thus, the February 1876 edition of University Magazine reported of the January IAA meeting,

Delegates from this college to the Convention of the Athletic Association started on the 6th ult., in accordance with a notice, signed by Mr. Webb, of Yale, as President of the Association, stating that the Convention would be held in New York, on Thursday, January 6th. For some unaccountable reason, the meeting, without an announcement of the fact having been made in any of the papers, was held the day previous, and our University, therefore, was not represented.

Football at Penn in the 1870s

Intramural soccer-style football games began to be played at the University of Pennsylvania by the early 1870s. University Record (1872), the Class of 1872 yearbook, says that “football, which has been greatly in abeyance for some time, took a vigorous start last fall in two games; one between the Sophomores and the Freshmen, in which the latter were victorious; and the other between the Seniors and the rest of the college. This latter contest was a most exciting one.”

A typescript sheet from 1914 at the Penn Archives related to the origins of football at Penn recounts the recollections of “John W. Townsend of the class of ’75” concerning the second game “of so called football” and contains the challenge offered by the senior class to the rest of the college for the second 1871 game.

The eighteen undersigned members of the senior class hereby do challenge an equal number — to be chosen six from each of the remaining classes — to play a match game of football on Saturday, December 9, 1871. The two sides will meet at the Philadelphia Cricket Club Grounds at 10 o’clock, each provided with a football. The side winning three mounts out of five will retain the two balls. Should this challenge be accepted you will please return with its acceptance the names of your eighteen players, after which no substitutes will be allowed.

If it was an exciting game, it was also a long one. The University Record reported, “After three or four hours of continual kicking, the Seniors obtained the best out of five ‘homers’ and were declared victors.” The yearbook also gives the final result as being 3-0, and describes the team of seniors as consisting of 13 players, while the underclassmen team had 22 players. (The enrollment information mentioned above indicates the senior class in 1871 consisted of 26 students at the start of the year. No number is given for the junior class, but the freshman class had 35 students, the sophomore class 31.) The account of the game ends, “the conflict was brought to a rather sudden conclusion however, a fear having entered our worthy Provost’s breast lest the window glass of the College might suffer damage.”

University Record (1873) reports the school “has fought countless foot-ball battle.” Yet, several pages later, the yearbook’s authors say, “We are authorized to state that football matches, rowing matches, walking matches, swimming matches, and even hymeneal matches (alas!) have been abandoned during the year 1872-3.” The abandonment was apparently temporary, for the University Record (1874) describes, “Our class has played the usual number of games of base ball, foot ball, and cricket.” A description of an athletics day concludes, “The contests were very close and interesting, the day’s sports being closed by a foot-ball match, ’74 and ’75 vs . ’76 and ’77.” The results are not recorded.

The June 1876 edition of Penn’s University Magazine, noting that “Foot ball at the University has now become so well established that it is necessary that we should have some fixed set of rules for our games,” offered a set of rules for the consideration of the school’s Athletic Association that fell somewhere between the “dribbling” and “handling” styles of play and were reminiscent of the Rutgers rules for football. Rule 7 stated, “The ball may be kicked or batted, but not thrown nor taken from the ground with the hands.” While players were allowed to make a fair catch, Rule 8 stated, “A ball shall not be held by any player unless he has made a ‘fair catch.’” Rule 10 states a player making a fair catch was entitled to a free kick, “Or a player having made a fair catch may continue to hit or kick the ball while running, but will not be allowed to hold it” (emphasis added). Rule 14 said, “No tripping, shoving, pulling, striking or hacking will be allowed under any circumstances, but shouldering will be allowed.” Each side was made up of 20 players. Goals were “thirty feet apart, at least fifteen feet high, with a cross rope ten feet high.” Rule 3 stated, “To win a game three goals out of five shall be necessary. To secure a goal the ball must pass between the goal posts, over the cross ropes, and touch the ground” (emphasis added).

The October 1876 edition of University Magazine noted, “We are glad to see that foot-ball is to be revived on the campus. The Athletic Association has appointed a committee whose duty it is to select a twenty from the members of the Association, to play a match game with a twenty from Columbia. All this is still in ovo, but if the students are properly stirred up, we have no doubt but that something will come of it. Let each class play every other class, and then the best men will make themselves apparent.” In the event, the Columbia game did not take place, but Penn challenged Princeton, which by this point had previously played and defeated Columbia, Rutgers, and Stevens College.

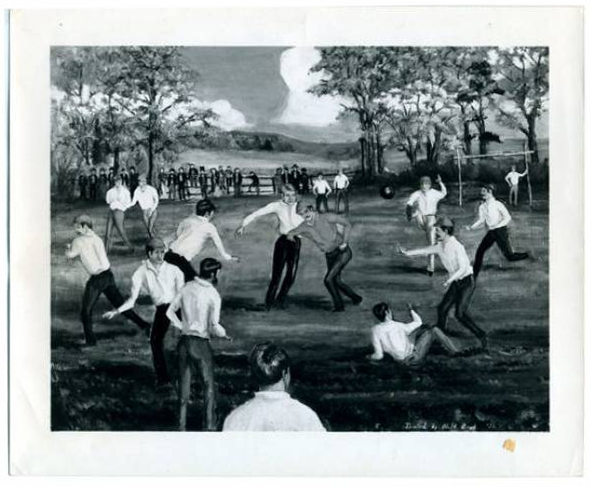

Penn’s first intercollegiate game took place against Princeton at Mannheim in Germantown on November 11, 1876. Penn lost, 6-0. The December 1876 edition of the University Magazine described,

In our Princeton match we have learned a lesson that we will never forget. When we went out upon the grounds and saw that we were pitted against men of at least double our weight, our first thought was that we had the advantage over them from the fact of our being more spry. Never was there a vainer hope. The first time the ball went out of bounds was the first time that we ever experienced what it was to be bucked. In our modest (to use a gentle expression) practicing we had sought to learn how to run and how to kick, but never had we thought of, much less seen, this practice of bucking. On Saturday, Nov. 11, we learned it, and the day is far distant when the recollection of that day will fade from our memories.

Although beaten as badly as we could be, we still must affirm that our men made quite as good an attempt at kicking as did our opponents. In all scrimmages, although our men were continually upset, somehow or other our men almost universally got the ball and passed it down toward the goal. Again, we clearly outran our Jersey friends, and in one instance, by sheer force of running, almost succeeded in obtaining a goal.

Before the return match at Princeton on November 25, which Penn also lost 6-0, Penn played an all-Philadelphia team, possibly at the Young America Cricket Ground at Wayne Junction, on November 18. University Magazine reported, “We had as easy a victory over them as the Spaniards did over us, obtaining four goals in little more than an hour.” (Apparently, “Spaniards” was a nickname for Princeton students?)

Writing of the game some 54 years later in an article called Recollections of a Football Fan, Davidson Kennedy describes,

You youngsters of the 1930 eleven wouldn’t recognize the 1876 game as the one you play today. In the first place, each side had twenty men, and they didn’t line up as you do now. It didn’t make any difference how many touchdowns a team made, because only goals from field counted in the scoring. All the emphasis was placed on kicking. It was real football.

It may have been “real football,” but wasn’t association football as it was being played in Britain, and its days at Penn were numbered.

The end of soccer-style college-based football

In 1874, Canada’s McGill University challenged Harvard to football and two games were played, one under the rules of the Boston Game favored by Harvard, the other under the rugby rules favored by McGill. Harvard unsurprisingly won the first game and then managed a scoreless draw against their Canadian opponents under the rugby rules. David Wangerin writes in Soccer in a Football World: The Story of America’s Forgotten Game (2006), “This proved a pivotal moment in American sport, for not only was Harvard immensely satisfied with its achievement, it also found rugby more to its liking. In October of that year, it played McGill again at rugby and won. The days of the Boston Game were numbered.”

Yale soon followed its rival Harvard in adopting rugby-style football. Wangerin writes, “With two of the nation’s most influential institutions converted…This left Princeton, with its fondness for the kicking game, to arrange matches with less prestigious schools, a situation it found intolerable.” By the time of the Intercollegiate Football Association meeting in November 1876, it was apparent that the only way to continue to expand intercollegiate football was by adopting a rugby-style code. Princeton, which had been so successful at soccer-style football with only one recorded loss in nearly 30 years of play, narrowly voted to adopt the rugby-style game. David Goldblatt writes in The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football (2006), “This culminated in the intercollegiate football association refining the rules of Harvard football to the point where most of the key elements of American football or gridiron — downs and yardage, blocking and scrimmaging — were now present.” Although the forward pass would not be made legal until 1906, the evolution of American gridiron football had begun.

In the Philadelphia area, the University of Pennsylvania adopted rugby-style football in 1877. Against Penn, Swarthmore played its first rugby-style football game in 1878, and Haverford played Swarthmore for the first time in 1879. Intercollegiate soccer would not be played in the United States for more than twenty years. When it did return, Haverford and Penn would be leading lights.

With universities leaving a vacuum in the development of the sport at this time, soccer in America would largely be played by middle- and working-class athletic clubs, clubs. In Philadelphia, these were often neighborhood-based clubs that played cricket in the summer and were, more often than not, English, Scottish, or Irish in their membership. Beginning around 1900, this process would in Philadelphia also include soccer teams from the cities more socially elite, upper-class cricket clubs, followed soon after by growing numbers of factory-backed teams.

A version of this article first appeared at the Philly Soccer Page on November 28, 2014.