My thanks to Roger Allaway, Brian D. Bunk, George Kioussis, and Tom McCabe for their comments and advice while researching this essay; the USSFA section would not have been possible without materials George generously shared with me. Thanks also to James Brown, David Kilpatrick, and Clive Toye. A special thank you to Roger Allaway for passing his Graham Guide collection on to me. Any errors below are my own.

While the 1950 Census recorded his occupation as a supervisor at a chewing gum factory, Scottish-born Bill Graham’s work life was more complicated than a single entry could describe. In the 1930s, Graham also ran for New York’s 7th Assembly District seat and edited a Scottish newspaper. More important for US soccer history, Graham began his long tenure as a soccer columnist for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1936, a position he held until the newspaper folded in 1955, returning to the paper for its brief revival as a Sunday weekly in 1960.[1] Graham for many years was also a contributor to Soccer News and the Midwestern Soccer News. Reminders of his main job at the Beech-Nut gum factory – and his life as a politician — were never far away: Graham was renowned for handing out packets of chewing gum.[2]

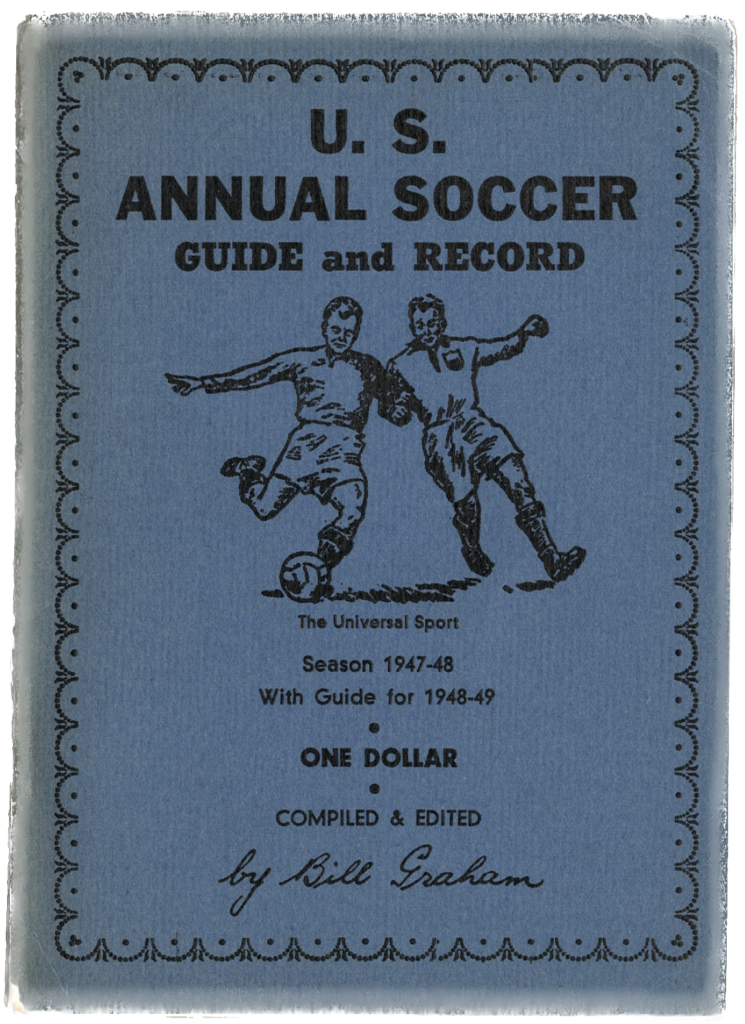

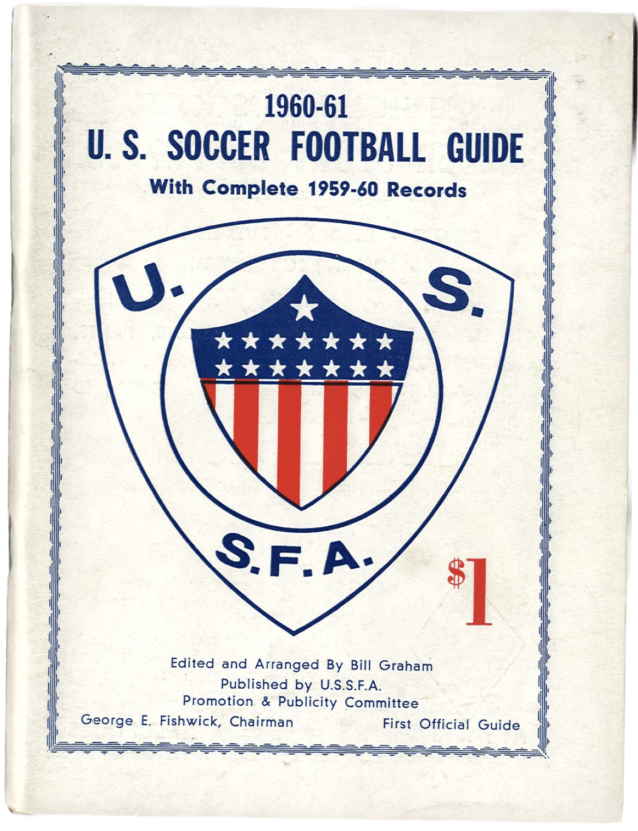

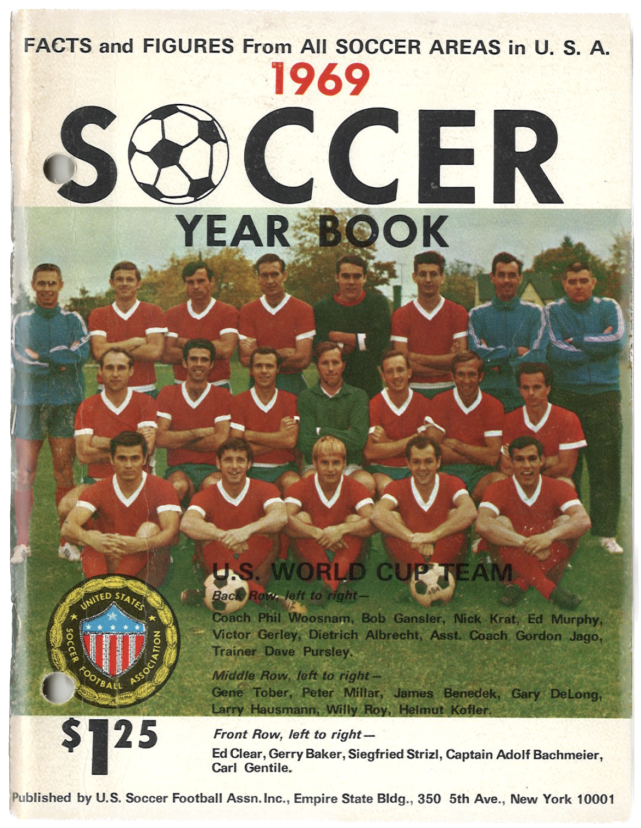

In 1948 Graham launched the U.S. Annual Soccer Guide and Record. Retitled as the North American Soccer Guide for the 1950 edition and colloquially known as the Bill Graham Guides or simply the Graham Guides, further editions were published by Graham each fall through 1956. After a three-year hiatus, the United States Soccer Football Association (USSFA) revived the Guide in 1960 as the U.S. Soccer Football Guide. Published under the auspices of the USSFA’s Promotion and Publicity Committee, Graham returned as editor through the 1968 edition as the Guide underwent several name changes, and was Honorary Editor for the 1969 edition. The history of the Graham Guides is thus a story in two parts, that of the self-published editions and then of the USSFA-published Guides. The few details available today about the production and distribution of the self-published Guides come from scattered remarks by Graham in his columns at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. More detail about the USSFA-published Guides can be found in the minutes of the USSFA’s annual meetings and Promotion and Publicity committee reports.

As a compilation of soccer activity across the United States, the Graham Guides followed in the footsteps of the Spalding Guides published between 1905 and 1924. But the Spalding Guides were backed by the leading sports goods company of the day. The soccer guides were just one among dozens of sports guides and manuals the company published and enjoyed all the benefits of promotion and distribution Spalding had at its disposal. In contrast, Graham alone was the force behind the Guide when he launched the first edition in 1948 and he created his own network of distribution. Graham’s mailing lists would later be used by the USSFA.

While their comprehensiveness could vary, as collections of results from local, regional, national, and international competitions; official communiques; reports on international tours; and commentary from leading figures on the issues of the day, the Spalding Guides and Graham Guides had no contemporary equals. They also often contain the only known images of historic players, teams, organizers, and administrators. A historian looking for basic information – names, dates, locations – begins with the Spalding Guides and Graham Guides to inform search strategies for deeper research in other sources. Thumbing through them can feel like entering “soccer in the US” into a search engine if the Internet had existed in 1915 or 1965. But print copies of editions of each of the annuals are exceedingly rare and, to date, only the Spalding Guides have been digitized.

The self-published Guide

William Graham was born in Scotland on September 23, 1893. The 1930 Census indicates Graham, then living at 263 60th Street in Brooklyn, arrived in the US in 1923, with his wife Helen and son William J arriving the following year. Graham’s occupation is recorded as foreman at a gum factory, while his wife was employed as a “janitress.”[3] By the 1940 Census, Graham and his family – which now included his US-born son Ronald — were living at 4705 Sixth Avenue in Brooklyn, the same address in the 1950 Census and also the address listed for the Guides self-published by Graham between 1948 and 1956.

Available for one dollar a copy and sized to fit in a pocket, little is known about the publishing history — such as numbers printed, numbers sold, ad revenue, printing costs, mailing costs, and so on — of the self-published Guides. References in Graham’s Brooklyn Daily Eagle columns give the sense of a growing, even thriving publication. In 1951, Graham reported the USSFA was sending copies of the Guide “to each of the other 73 sister nations” in FIFA “as a good will gesture.”[4] After the publication of the 1952 edition, Graham reported the Guide was available “in more than 30 major city public libraries,” with international orders being received from as far afield as “Roumania, Switzerland and the Philippines.”[5] The next year, Graham reported orders for the 1953 edition had “far surpassed those of the previous five editions” and was “a sellout within five weeks.” The FIFA-member mailing list had grown to 81 countries, although it is unclear if these copies were purchased by the USSFA for distribution to fellow national associations or resulted from direct sales.[6] Graham reported reviews of the 1953 Guide were to appear in “French, German and Swiss newspapers” and Sir Stanley Rous, secretary of England’s Football Association, wrote him to say the Guide would be mentioned in the association’s Monthly Bulletin, “which has worldwide circulation.”[7] By now the Guide was available “in more than 50 major-city libraries from coast to coast” with sightings of the Guide reported in Chile and Uruguay.[8] He received orders from “Queen Elizabeth and Ghazi Shah Mahmud Khan of Afghanistan.”[9]

The Guide’s apparent growth did not come without some controversy. In a Brooklyn Daily Eagle column published in December 1952, Graham had described American League News, which covered the American Soccer League (ASL), as “incoherent and asinine following a widespread reprimand for injecting politics into Stadium promotions.” Given repeated missteps by the ASL, Graham suggested the league should “listen respectfully to any and all promotion suggestions.”[10] According to Graham, an unnamed “fledgling writer of the American League News” responded by describing his criticism of the ASL as “a fine example of his gratitude when he gets monies for ads, news matter gratis and unselfish co-operation in the promotion” of the Guide. Graham explained, the unnamed writer “refers to a $40 ad in the North American Soccer Guide, the purchase of two single copies by loop officials, others being freeloaders, and the mailing of a two-page throwaway,” adding, “Believing the $40 was paid only for value received in the ad the Guide has notified the American League that the space will not be available in future editions.”[11] Two days later, Graham wrote, “Do patrons of Sterling Oval know that the Soccer News and the North American Soccer Guide are barred from sale inside when the New York Americans are home?”[12] Whether the ban was in response to Graham’s criticism of the ASL is unclear.

Given his reports on the Guide’s continuous growth it is difficult to answer why Graham published no further editions after 1956. One factor could be the demise of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1955: Did the loss of income from his newspaper work affect his ability to continue to self-publish and distribute the Guide? There is some evidence this may have been the case. In a discussion of the Guide at the USSFA annual meeting in July 1968, association vice president Erwin A. Single said, “The U.S.S.F.A. stepped into the picture when [Graham] couldn’t make ends meet anymore.”[13] Another factor could have been simple fatigue. Graham was 63 years old in 1956 and perhaps simply needed a break. He had spent nearly two decades as a columnist for the Brooklyn newspaper, and published the Guide, all while working full time as a supervisor at Beech Nut. Dependent on the self-reporting of soccer activities from local leagues and associations, compiling the Guide was surely taxing, more so in an era before the Internet and easy desktop publishing.

Not that Graham suspended soccer-related work along with the Guide. A newspaper article in April 1957 suggests he had moved into public relations, crediting the source of information on an upcoming US tour by German club Kaiserslautern to “Bill Graham, of the Service Bureau.”[14] Another article in November 1957 said Graham was publicity director for New York’s German American League. That article also indicated Graham had not completely left the publishing business. Noting “the 1957-58 Soccer Football Rules book” was now available, the report said, “If you would like a copy, mail 20 cents to the North American Soccer Guide.”[15] The address listed for the Service Bureau and the North American Soccer Guide was Graham’s home address in Brooklyn.

The USSFA revives the Guide

As we have seen, the USSFA used the Guide to promote awareness of its activities and soccer in the United States from at least 1951. At the forty-fourth annual meeting of the USSFA in Milwaukee in June 1960, George E. Fishwick, chairperson of the association’s Promotion and Publicity committee and publisher of the Chicago-based National Soccer News, reported the USSFA would begin publishing the Guide: “Plans have been put into effect to publish an Official U.S. Soccer Guide, which will be distributed next September. Bill Graham of New York has accepted the task of editing the publication, but this endeavor will become a part of the coming season’s financial budget.” A sum of “up to” $2000 was allocated for reviving the Guide, equal to about $20,600 today: “the guide is being budgeted to bring in a profit.”[16] While $2000 may seem a pittance today, the figure was a remarkable increase in funding for the Promotion and Publicity Committee. The 1960 Treasurer’s Report noted the committee’s expenses for 1958-59 were $81.06, and $200 for 1959-60.[17] Any acrimony that might have existed between Graham and the ASL was by now forgotten. Among those who spoke in support of the USSFA reviving publication of the Guide was ASL delegate Anthony Uhrik.[18]

A year later at the annual USSFA meeting in Baltimore in June 1961, Uhrik spoke to “highly commend Mr. Graham and Mr. George Fishwick for the successful revival of the official Soccer Guide under the auspices of the United States Soccer Football Association.” Uhrik added, “We recommend that this official Soccer Guide be continued on an annual basis and efforts should be made with these instructions inside as well as outside soccer circles.” Published in fall 1960, the 1960-61 U.S. Soccer Football Guide with Complete 1959-60 Records had a cover price of $1. The Promotion and Publicity Committee reported 2500 copies had been printed “in anticipation of better sales than normally are realized for a guide such as this.” The committee’s report noted, “Though sales topped similar issues when printed by an individual [Graham] they did not reach the 2000 mark.”[19] This suggests sales of the self-published Guides never exceeded 2000 copies per edition. While “encouraging,” purchases of the first USSFA-published Guide (buyers also received a free copy of the USSFA-printed Laws of the Game) were disappointing with the number sold “not indicative of the potential sales.”[20]

The committee also reported that 266 copies of the Guide were “turned over to the office of the USSFA, which the Prom & Pub Committee considered as revenue, though there was no actual transfer of funds.” Subtracting $266 from the reported total sales revenue of $1666 suggests 1400 copies were sold in addition to the 266 copies given to the USSFA. According to the committee, Graham was paid an editor’s fee of $250, equivalent to about $2500 today (a later report said Graham “works for free”[21]). Additional expenses included $95 for “pluggers” mailed directly to subscribers to Soccer News (New York) and National Soccer News (Chicago) to promote the new Guide. Combining ad revenue with money earned from sales resulted in total income of $2011.10 against total expenses of $2284.99, which meant the debut USSFA edition of the Guide lost $273.89.[22]

With plans to reduce the print run of the next edition, raise the cover price to $1.25, lower postage costs, and increase ad revenue, expectations were that future income from the Guide would be higher. Instead, the 1961-62 U.S. Soccer Football Guide, which was mailed with a copy of Soccer Plays Illustrated, an illustrated guide soon better known as Sandlot Soccer, saw a decline in sales: “Sales were far from what was expected, being approximately 1200 copies of the 2000 printed.”[23] The USSFA’s fiscal year ran June 1 to May 31. With the Guide typically published in October, the USSFA’s yearly reports reflected at best only eight months of sales. Beginning with the 1961-62 USSFA Treasurer’s Report, sales of the preceding year’s Guide after the end of the fiscal year in which it was published were also reported. But these sales were rarely substantial and between 1960 and 1970, each edition of the Guide ran a deficit ranging from $430 to $1650.

A recurring problem was the lack of what might be called institutional sales: sales to the USSFA’s regional associations, affiliated leagues, and teams rather than to individuals. Graham had previously underscored the importance of such sales when he reported USSFA purchases of the self-published Guide in 1951. Fishwick had emphasized the importance of institutional sales from the start of the USSFA’s involvement with the Guide, saying at the 1960 Annual Meeting, “[W]e will call upon state organizations and clubs and leagues for information, for support in sales and support in ads…so that instead of the United States Guide being a cost to the USSFA, it will be a profitable venture”[24] Fishwick observed in the 1961-62 Promotion and Publicity Committee report, “Figuring 700 senior teams now under the jurisdiction of the U.S.S.F.A., we are selling less than 2 copies per team.”[25] This “If only each team bought two copies” argument became a familiar line in subsequent annual meetings and reports.

The lack of institutional purchases from USSFA-affiliated organizations and teams was but one factor in the Guide’s disappointing sales after the USSFA became its publisher. Publication of the 1966 edition was delayed “due to the slow arrival of a few necessary contributions.”[26] Much of the material included in the 1967 edition was not received by Graham until after the new year, months after the typical October publication date. These delays were further compounded by labor problems at the press Graham employed to print the Guide.[27]

But a larger issue was a simple lack of awareness of the Guide among USSFA members. At the 1968 annual meeting, a call was made to end the USSFA’s financing of the Guide and to reallocate those funds toward youth development. It soon became clear this call grew from a misunderstanding of how the Guide was funded and who received its sales revenue. But in the extensive discussion of the Guides’ value to the USSFA that followed, one delegate felt compelled to engage in a display of show and tell. Holding a copy of the latest edition, Southern New York delegate John Stox explained, “Gentlemen, if you were confused, this is the Soccer Guide. Some of you have never seen it. It is almost, in my conception, the history from year to year of our association, with all the contributions from the various states.”[28] Still, if the value of the Guide as a yearly record of soccer activities was generally accepted by the delegates, some doubted its value in promoting soccer to those unfamiliar with the sport. As Washington State delegate Edmund Craggs commented, “We know the Soccer Guide is a good guide, a good thing for those that are actually interested in soccer. But, for — as far as publicity for outsiders, it’s practically useless.”[29]

Craggs’ comment speaks to two promotional needs, that of informing USSFA-affiliates of the activities of fellow members, and that of engaging a wider public with little knowledge of soccer. When he launched the Guide in 1948, Graham’s intended audience was the American soccer community, “those that are actually interested in soccer.” Certainly, Graham understood its value as a reference work for reporters and editors who might cover the sport; his descriptions of increasing library holdings of the self-published Guides underscore that. The inclusion of copies of publications like Sandlot Soccer with sales of the Guide suggests the Promotion and Publicity Committee recognized the limitations of the Guide in reaching “outsiders.” By also receiving a copy of Sandlot Soccer, buyers of the Guide could become advocates for soccer themselves by passing along Sandlot Soccer to kids and to adults involved in organizing and administrating youth sports. In the end, the delegates voted to continue the association’s publication of the Guide.

No one blamed Graham for the disappointing sales and there was a general understanding within the USSFA that the value of the Guide could not be reduced to a simple calculation of profit and loss. USSFA Treasurer Wilson Hobson said at the 1966 Annual Meeting, “The Guide has averaged us a deficit of only $1,000 a year. I feel that it has promotional and publicity value of much more than $1,000 a year.”[30] Members praised Graham’s efforts, calling the Guide a “compact pocket-book size masterpiece,” and “an outstanding piece of work that has great practical value, educational and historical.”[31] Nor was his work with the USSFA in this period restricted to the Guide alone. The 1964 Promotions and Publicity Committee report noted Graham also “handles the physical job of production and distribution of the USSFA newsletter,” which was issued “at intervals of three weeks” between October and the “close of the soccer year in Mid-June.”[32] In the lead up to the 1970 World Cup, Promotion and Publicity Committee press releases covering the schedule and locations of USSFA World Cup qualifiers “were distributed through the large mailing list of Bill Graham.”[33] In matters of print and distribution, the USSFA repeatedly, if not exclusively, turned to Graham.

In 1968 at age 76, Graham edited his eighteenth and last edition of the Guide, now retitled the Soccer Year Book, a corpus of more than 2600 pages (this does not include his output as a columnist). The United States Soccer Football Association 1970 Yearbook published in 1969 lists him as Honorary Editor. At the USSFA’s 1970 annual meeting in Chicago, USSFA president Erwin A. Single offered a certificate of appreciation for Graham’s “long and devoted work compiling national statistics and reports from state associations and local leagues for use in the USSFA annual yearbook,” but Graham was not present to accept.[34] Clive Toye, editor of the 1971 edition, Soccer nineteen seventy-one yearbook, remarked a year later, “After spending many hours writing, editing, headline-writing, measuring, cutting, gluing and designing this Year Book, I can not help admiring Bill Graham who had suffered the same problems through so many Year Books.”[35]

Bill Graham died May 3, 1973, just a few months shy of his eightieth birthday. In a memorial contained in the next edition of the Guide, now titled Soccer 1973, Single wrote that Graham did not live to see “the newest issue of the work he originated,” his “labor of love.”[36]

Conclusion

What are we to make of the contradiction between Graham’s descriptions in his Brooklyn Daily Eagle column of the self-published Guide as a growing publication and discussions in USSFA annual meeting minutes and Promotion and Publicity Committee reports of disappointing sales and even a lack of awareness of the USSFA-published Guide in US soccer circles? Does a meaningful contradiction exist? Not really. Graham describes the rise of a publication from its launch in 1948 to selling out the 1953 print run. That growth was entirely the result of Graham’s efforts and was surely extremely satisfying. Definitive sales figures for the self-published Guides are not available so we don’t know what losses were accrued before or after the sellout of the 1953 edition. Nor can we be certain what factors led to Graham ending production of the self-published Guide after the 1956 edition when he could no longer “make ends meet.” But one individual successfully bringing to press and distributing nine editions of a comprehensive compilation of the soccer activities of an entire country is a remarkable achievement. It is no wonder Graham reported its development and growth in positive terms.

The USSFA simply had different measures of success. As described above, taking over publication of the Guide represented a huge increase in the Promotion and Publicity Committee’s budget. From the start, the Guide was expected be a source of revenue for the USSFA, that the association’s investment in it would return a profit. Discussions at USSFA annual meetings of disappointment in the numbers sold of USSFA-published editions of the Guide reflect that expectation. Nevertheless, the understanding that the Guide’s value existed beyond obvious measures of profits and loss prevailed. To the present-day reader, there is something hopeful in USSFA administrators and delegates recognizing the connection between the need to record and appreciate soccer’s history in the US with efforts to promote and grow the sport. And if the USSFA’s Treasurer’s Reports are any indication, the sport was undeniably growing. Between 1960 and 1970, the association’s coffers grew from $21,533.86 to $114,461.75, a nearly 432 percent increase.[37] This growth was accompanied by the understanding that the work of the Promotion and Publicity Committee must become a “full-time operation” rather than “the volunteer spare-time conditions that have existed in the past.”[38] In order to capitalize on growing interest in soccer in the US and keep up with increasing demand for information about the activities of the USSFA and its member organizations, the association had to professionalize its operations. By the end of Graham’s tenure as editor of the USSFA-published editions, sales of the Guide were also growing even if it still wasn’t breaking even. Rebounding from the poor sales numbers following the delayed 1966 and 1967 editions, the Guide finally breached the 2000 copies threshold: the 1968 edition sold 2200 copies, the 1969 edition at least 2500 copies.[39]

Remarkably, Graham was never inducted into the National Soccer Hall of Fame. Nevertheless, his work over three decades as a newspaper columnist makes him a notable figure in US soccer history. Combining that with his work over three decades compiling the Guides makes him a leading figure in the era between the beginning of the second ASL and the start of the North American Soccer League. Indeed, it is difficult to think of someone during this period whose body of work is more significant who is not a player or an administrator. His time editing the USSFA-published Guides coincides with the beginning of the association’s transformation from a volunteer-run organization into the professionally organized and comparative giant that US Soccer is today. The beginnings of soccer’s upward rise to its current place in the US sport landscape can be traced to the same period.

We know the print runs for both the self-published and USSFA-published Graham Guides were small. Printed with paper covers and bound by staples until the 1970 edition after Graham was no longer involved as editor, the Guides weren’t published in a form made to last. Consequently, the condition of existing copies varies greatly. The digitization of the Graham Guides will ensure their preservation while also considerably broadening their availability, thus facilitating new research into the era they detail. Maybe then Graham’s contributions to the history of soccer in the US will receive the long overdue recognition he so richly deserves.

Endnotes

[1] US Census Bureau, 1950 Census of Population and Housing, Brooklyn, Kings County, New York (24-918), sheet 15, House 4705B, Serial Number 187; Sherman Bethune, “Take It from Me,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle- Home Talk, Nov. 13, 1935, The Item Section, 4; Sherman Bethune, “Take It from Me,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle- Home Talk, Dec. 4, 1936, The Star Section, 4; “Eagle Back In Service Of Brooklyn,” Brooklyn Eagle, Oct. 23, 1960, 1.

[2] Erwin Single, “Bill Graham: A Memory,” in Soccer 1973 (New York: United States Soccer Football Association, 1973), 9; Sherman Bethune, “Take It from Me,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle- Home Talk, Mar. 23, 1934, The Star Section, 16; Jack Butler, “Sports,” The Tablet (Brooklyn), Nov. 11, 1953, 18.

[3] “William Graham: Social Security Death Index (SSDI) Death Record,” GenealogyBank, accessed Mar. 16, 2023, https://www.genealogybank.com/doc/ssdi/news/112D012BA00431D0?h=1&fname=William&minit=&lname=Graham&fullname=&kwinc=&kwexc=&birthy_0=1893&birthy_1=&deathy_0=1973&deathy_1=&ssnum=&ssstate=&citylast=Brooklyn&cntylast=&statelast=NY&ziplast=&nonusloc=&sid=edjntngcxhtrappwefkuqabrnipyseyu_wma-gateway005_1678975300914; US Census Bureau, 1930 Population Schedule, Brooklyn Borough, Kings County, New York (24-1728), sheet 7B, House 63; US Census Bureau, 1940 Population Schedule, Brooklyn Borough, Kings County, New York (24-8212), sheet 9A, House 202.

[4] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov. 27, 1951, 16.

[5] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Apr. 15, 1952, 17; Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan. 15, 1952, 13.

[6] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Oct. 10, 1953, 15; Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 8, 1953, 23.

[7] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 29, 1953, 15; Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan. 5, 1954, 15.

[8] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan. 15, 1954, 14; Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Feb. 2, 1954, 13.

[9] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov. 9, 1954, 15.

[10] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 2, 1952, 14.

[11] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 16, 1952, 14.

[12] Bill Graham, “Soccer,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 18, 1952, 20.

[13] Minutes: Fifty-second Annual Meeting of the United States Soccer Football Association Incorporated. Held at The Shamrock Hilton Hotel, Houston, Texas, July 13th and 14th, 1968, 15.

[14] Ken Christiansen, “Sports Shorts,” Greenpoint Home News, Apr. 18, 1957, 5.

[15] Ken Christiansen, “Sports Corner,” Greenpoint Home News, Nov. 29, 1957, 5.

[16] George E. Fishwick, “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1959-1960, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 44th Annual Meeting held at Hotel Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, June 25th and 26th, 1960, 27.

[17] W.T. Hobson, Jr., “Treasurer’s Report, 1 June 1959 to 31 May 1960,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1959-1960, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 44th Annual Meeting held at Hotel Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, June 25th and 26th, 1960, 19.

[18] Minutes: Forty-Fourth Annual Meeting of the United States Soccer Football Association Incorporated. Held at Hotel Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Saturday and Sunday, June 25th and 26th, 1960, (Master Reporting Company), 12.

[19] George E. Fishwick, “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1960-1961, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 45th Annual Meeting held at Hotel Emerson, Baltimore, Maryland, June 17th and 18th, 1961, 30.

[20] Minutes: Forty-Fifth Annual Meeting of the United States Soccer Football Association Incorporated. Held at Hotel Emerson, Baltimore, Maryland, Saturday and Sunday, June 17th and 18th, 1961, (Master Reporting Company), 26.

[21] Minutes: 1968, 16.

[22] “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee, 1960-1961” 30. There are discrepancies between the income/expense figures in the Promotion and Publicity Committee report and the Treasurer’s Report. For example, the Promotion and Publicity Committee reported estimated costs of the 1960 Guide as $2177.20 while the Treasurer’s Reports listed the costs as $2284.99. See W.T. Hobson, Jr., “Treasurer’s Report, 1 June 1960 to 31 May 1961,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1960-1961, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 45th Annual Meeting held at Hotel Emerson, Baltimore, Maryland, June 17th and 18th, 1961, 32.

[23] George E. Fishwick, “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1961-1962, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 46th Annual Meeting held at Hotel Wolverine, Detroit, Michigan, July 14th and 15th, 1962, 25-26.

[24] Minutes: 1960, 13.

[25] “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee, 1961-1962,” 26.

[26] George E. Fishwick, “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1966-1967, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 51st Annual Meeting Held at the Pick Carter Hotel, Cleveland, Ohio, July 1st and 2nd, 1967, 51.

[27] George E. Fishwick, “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee, Season 1967-68,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1967-1968, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 52nd Annual Meeting Held at The Shamrock Hotel, Houston, Texas, July 13th and 14th, 1968, 51; Minutes: 1968, 15.

[28] Minutes: 1968, 16.

[29] Minutes: 1968, 16.

[30] Minutes: 1966, 19.

[31] Minutes: Forty-Seventh Annual Meeting and Fiftieth Anniversary of the United States Soccer Football Association Incorporated. Held at Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York, New York, July 5th, 6th and 7th, 1963. 24; George E. Fishwick, “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee 1964-1965,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1964-1965, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 49th Annual Meeting held at The Flying Carpet Motor Inn, Rosemont, Illinois, July 3rd and 4th, 1965, 25.

[32] George E. Fishwick, “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee 1963-64,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1963-1964, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 48th Annual Meeting held at Hotel Mayfair, Los Angeles, California, July 11th and 12th, 1964, 43.

[33] “Promotion & Publicity Committee Report, 1968-69,” 37.

[34] Minutes: Fifty-fourth Annual Meeting of the United States Soccer Football Association, Inc. Palmer House -Chicago, July 10, 11, 12 – 1970, 24.

[35] Clive Toye, “Report of the Chairman of the Promotion and Publicity Committee,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1969-1970, Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the at the 54th Annual Meeting Held at The Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, Illinois, July 10th, 11th & 12th, 1970, 44.

[36] Single, “Bill Graham: A Memory,” 9.

[37] “Treasurer’s Report, 1960,” 20; Thomas E. Sager, “Treasurer’s Report, 1 June 1969 to 31 May, 1970,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1969-70, Submitted to the Council of the US.S.F.A. at the 54th Annual Meeting Held at The Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, Illinois, July 10th, 11th & 12th, 1970,” 30.

[38] “Report of the Promotion & Publicity Committee 1966-67,” 52.

[39] Sales numbers are determined by dividing the reported income of each edition in Treasurer’s Reports by the price of a copy of the Guide. Because I do not have the 1971 Treasurer’s report, the number of copies sold of the 1969 edition does not include further sales in the following year. See W.T. Hobson Jr., “Treasurer’s Report, 1 June 1968 to 31 May 1969,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1968-1969. Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 53rd Annual Meeting Held at The Americana Hotel, Miami Beach Florida, July 4th, 5th & 6th, 1969, 35; W.T. Hobson Jr., “Treasurer’s Report, 1 June 1969 to 31 May 1970,” in Reports of the Officers and Committees, United States Soccer Football Association, Season 1969-1970. Submitted to the Council of the U.S.S.F.A. at the 54th Annual Meeting Held at The Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, Illinois, July 10th, 11th & 12th, 1970, 29.

Well researched and a fascinating read but ,given the author, that does not surprise me! JC

Pingback: “Graham Guides” digitization project fundraiser launched – Society for American Soccer History

Pingback: The Bill Graham Guides Collection is now available! – Society for American Soccer History